The Ku Klux Klan, the white supremacist movement, finds itself on the ragged fringes of American society today, a miserable relic of a bigoted era when ethnic chauvinism, intolerance and racism were fairly common in the United States.

But almost a century ago, the white-hooded order was riding high, having elected like-minded governors in Texas, Oklahoma, Colorado, Oregon and Indiana and having won control of state legislatures, town councils, law enforcement agencies and school boards across America.

Buoyed by its growing popularity, the KKK, in a show of hubris and force, staged an unprecedented mass rally in Washington, D.C. on Aug. 8, 1925 during which 35,000 to 45,000 unmasked white-robed marchers triumphantly paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue, savoring the applause of the crowd.

The spectacle was covered by The New York Times. “Sight Astonishes Capital,” the headline over the story read.

Within a few years, the KKK was in disarray, felled by scandal and political setbacks, never again to regain its influence.

In One Hundred Percent American: The Rebirth and Decline of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s (Rowman & Littlefield), Thomas R. Pegram, a professor of history at Loyola University Maryland, documents its rise and fall with thoroughness and expertise.

The original KKK was born shortly after the Civil War, founded in Tennessee by disgruntled former Confederate soldiers bent on driving newly-enfranchised African Americans from public office in southern states. Klan violence and intimidation prompted the U.S. Congress to pass anti-KKK legislation. But even as it was suppressed, the Klan could take solace from the fact that white, conservative rule, with its maze of Jim Crow laws and segregation, had returned to the South.

The KKK was reborn in 1915, resurrected by William Simmons, the son of a Klansman in Alabama. D.W. Griffith’s silent film, The Birth of a Nation, buffed up the KKK’s image by portraying the 19th century Klan heroically.

Resolutely antisemitic and anti-Catholic, and staunchly upholding traditional Protestant values, the KKK was, as Pegram observes, “an aggressive counterforce to cultural pluralism.”

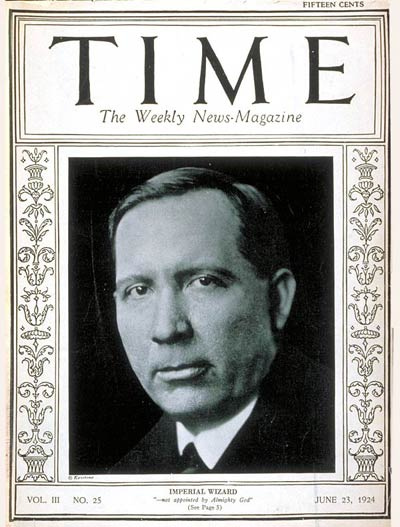

The Klan emerged at a time when non-Protestants began challenging the Protestant domination of politics and the arts. Dismissing pluralism as a model for American democracy, the KKK’s Imperial Wizard, Hiram Evans, claimed that, as descendants of the first European inhabitants of the United States, they had a “prior right to control America.”

Eligible to join were native-born Americans who endorsed, among other precepts, the “Christian religion,” white supremacy and states’ rights. Southern Anglo Saxons were its most prominent members, but in the northeast, upwards of 40 percent were of German origin.

Although Americans of Greek, Italian, Czech, Polish and Jewish descent were recognized as white under U.S. naturalization law, the Klan deemed anyone of non-Anglo Saxon or non-Nordic ancestry as racially inferior.

The KKK was opposed to open immigration, regarding it as a threat to America’s “racial integrity.” And Klan publications denounced Jewish and Catholic influence in the commercial film industry.

Klan popularity hit a peak in the 1920s, when as many as four million Americans were members. But by 1930, membership had declined to about 37,000, he writes.

“Along with the disaffection from unmet political promises and the web of moral scandals and power disputes that gripped the leadership, second thoughts of hesitant Klansmen about the connections between militant Protestant activism and violent retribution contributed to the loss of energy that beset the Klan movement,” he explains.

The Klan’s downfall was also a function of its violence, much of which occurred in the south and southwest.

Finally, the Klan was outmaneuvered by a coalition of Americans, with Catholics in the forefront, who objected to its aggressive conception of Protestant superiority.

By the 1940s, the KKK had splintered into a collection of rival associations. And the revived Klan during the civil rights era of the 1950s and 1960s represented, he says, “a resentful outlaw resistance against the shifting American mainstream of cultural and civic values.”

Today, with only a few thousand members, the Klan has no “realistic hope” of achieving mainstream acceptance or influence. It is, for all practical purposes, dead in the water.

Pegram, in this valuable work, puts the Klan into historical perspective.