Long after his nine-hour documentary on the Holocaust, Shoah, was released in 1985, the French filmmaker, Claude Lanzmann, reviewed footage he had been forced to cut. He was probably flabbergasted by what he had left out, particularly an intriguing interview with Rabbi Benjamin Murmelstein, the last living “elder” of a Nazi ghetto.

Murmelstein, who died in 1989, was an historic figure. He worked with the Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann in Vienna to facilitate Jewish emigration from German-occupied Austria, and he was the third and final president of the Jewish Council in Theresienstadt, the “model” Nazi camp in German-conquered Czechoslovakia.

Having decided that a film about Murmelstein could be justified and would be sufficiently interesting, Lanzmann made The Last of the Unjust, a blend of old and new material that offers viewers yet more insights into the Holocaust.

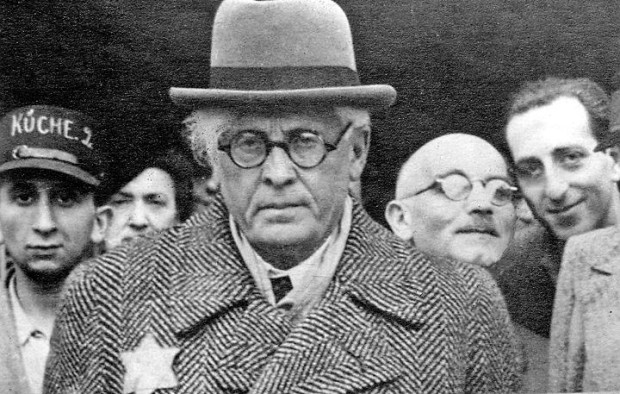

Claude Lanzmann, left, interviews Benjamin Murmelstein

Scheduled to open in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver toward the end of this month, The Last of the Unjust is a profile of Murmelstein, who has been condemned as a collaborator yet hailed as a hero, and a portrait of Theresienstadt, a camp for so-called privileged Jews that lay 60 kilometres northwest of Prague.

Clocking in at three hours and 38 minutes, the film is bloated yet compelling. It could and should have been edited to a manageable length, but even in its present form, it passes muster.

Although Murmelstein is at the center of The Last of the Unjust, Lanzmann is hardly a peripheral character, persistently posing questions, visiting relevant sites and making pertinent observations. As it opens, he’s standing on a railway station platform in the Czech town of Bohusovice, where 140,000 European Jews disembarked from 1941 to 1945 on their way to Theresienstadt, only three kilometres away.

SS militiamen met the new arrivals, whose collective reactions ranged from curiosity to doubt to terror. As they would shortly discover, Theresienstadt was a transit camp, a way station to Auschwitz-Birkenau. As he walks slowly through the forlorn camp, its buildings now in a state of disrepair, Lanzmann reads the testimonies of inmates.

The scene shifts to Rome, where Murmelstein lives. After the war, he was charged with being a collaborator and imprisoned for 18 months. Having been acquitted, he was set free. Although he’s already written a book about his experiences, he’s none too keen to revisit the past. He agrees to look back only because of Lanzmann’s persuasive powers. It’s a “belated epilogue,” says Murmelstein, a self-assured, articulate and cherubic person who speaks in German.

Asked if he’s ever been filmed, Murmelstein replies in the affirmative. In 1944, Germany released a notorious propaganda film about Theresienstadt, but the segment in which he appeared was excised by the Nazis because the man who had sat next to him, Paul Eppstein, his predecessor, was shot dead a few weeks later.

By turns contemplative and combative, Murmelstein has no illusions about the role he played, calling himself a “comic marionette.”

At this juncture, the film backtracks, taking us back to June 1938, when he began working for the Jewish community in Vienna as an administer. In this capacity, he worked for Eichmann on emigration issues. Murmelstein has a rather low opinion of his boss, saying he “knew things superficially.”

And as far as he’s concerned, Eichmann was not bland, as the observer Hannah Arendt suggested during his show trial in Jerusalem three decades later. To Murmelstein, Eichmann was corrupt and venal, a gangster who profited from the sale of 400 Colombian visas. And he personally desecrated a synagogue in Vienna during Kristallnacht in November 1938. “He was a demon,” says Murmelstein, who feared Eichmann but maintained his composure in his dealings with him.

Lanzmann wonders why Murmelstein did not leave Austria . “I had something to accomplish,” he says in reference to his work on emigration. “I thirsted for adventure.” The job gave him personal satisfaction and a sense of power, he concedes.

In a digression on emigration, Lanzmann claims that Polish Foreign Minister Joseph Beck devised the scheme to resettle European Jews on the island of Madagascar. The Germans considered the proposal, and Eichmann expressed enthusiasm, but wartime conditions rendered it unachievable. In another digression, Lanzmann focuses on Nisko, a town in Poland where Germany planned to build a Jewish reservation.

Returning to Theresienstadt, Lanzmann launches into a discussion about the appalling conditions there and the reign of terror the Nazis inflicted on its Jewish captives. Murmelstein says that the camp was a “lie” from start to finish, designed to fool the International Red Cross, which sent naive representatives there on inspection trips, and to lull Jews into a false sense of complacency.

Murmelstein arrived in Theresienstadt in January 1943 as a deputy to the camp elder and as a “Category A” Jew, meaning he would be exempt from hard labor and deportation to Auschwitz,

He grows visibly animated when he defends himself. He admits he had a reputation as a mean-spirited leader, but adds, “I couldn’t afford the luxury of being a gentleman.” He acknowledges that he cooperated with the Germans in “embellishing” the camp’s image by means of the propaganda film the Nazis produced, but later claims that he had “nothing to do” with that “circus” and “staging.”

Murmelstein says he brought “order” to Theresienstadt, thereby persuading the Nazis not to close it or deport the balance of its Jewish prisoners. In a related comment, he claims he refused to draw up a list of Jews to be deported in October 1944.

In yet another admission, he says he had no knowledge that Auschwitz was an extermination camp. He thought it was a “family camp.” But he knew that the Nazis were up to no good in the east.

In conclusion, Murmelstein asks for understanding. An “elder,” he muses, can be condemned but should not be judged.

Like Chaim Rumkowski of the Lodz ghetto, Murmelstein was placed in an impossible bind. If he cooperated with the Germans, he might be able to save Jewish lives, but would still be regarded as a traitor. If he refused, he would be killed and replaced by a compliant administrator who would do their bidding.

That, in essence, is the terrible dilemma that Lanzmann explores in this thoughtful movie.

Show times:

Vancouver – Vancity Theatre, 1181 Seymour St.April 27-May 1Montreal – Cinema du Parc – 3575, Avenue du ParcApril 27