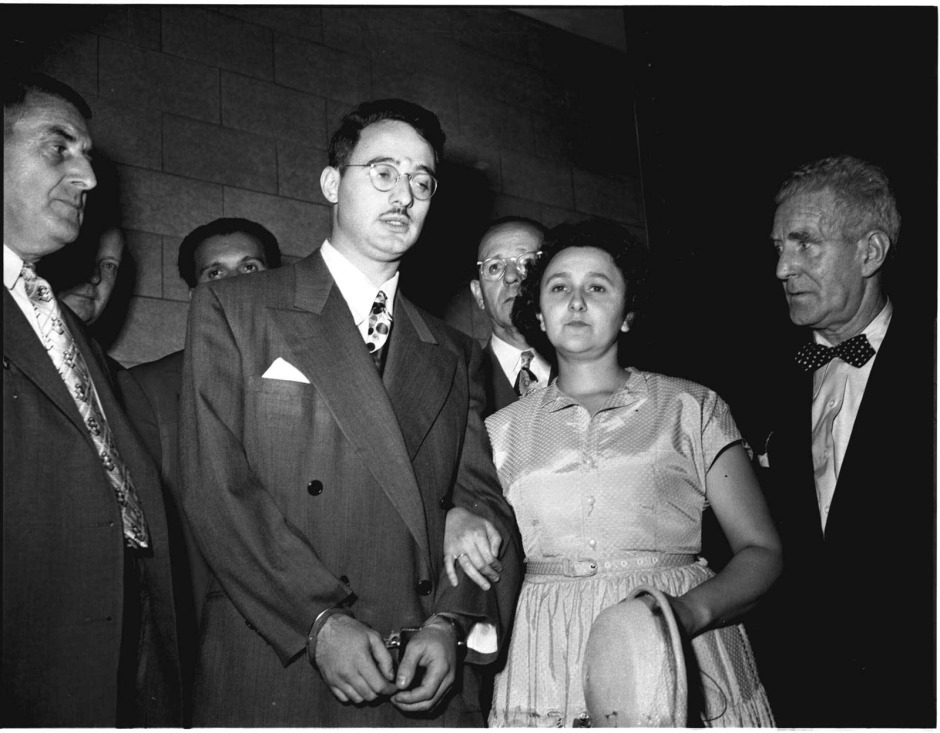

Although they were tried and executed more than half a century ago, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg’s names remain familiar to most Americans.

Executed on June 19, 1953, after their conviction for conspiracy to pass atomic bomb secrets to the Soviet Union during and after World War II, the Rosenbergs were at the center of one of the most famous and controversial espionage cases of the 20th century.

Their trial drew world-wide attention, and since that time, literally thousands of articles and books have been written about the case and its ramifications for the United States, the Cold War, and the American Jewish community.

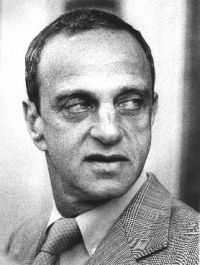

The celebrated case has again been in the news, following the death of Ethel’s brother, David Greenglass, this past July1, at age 92. The news of his death was reported yesterday.

Greenglass, who had also been arrested as part of the espionage ring that included the Rosenbergs, pleaded guilty in exchange for testifying against them — testimony that he would in later years admit had been false.

He served 10 years of a 15-year sentence and was released from federal prison in 1960. Another defendant, Morton Sobell, was convicted and served 18 years of a 30-year term.

Greenglass had been drafted into the U.S. Army in 1943 and was assigned as a machinist to the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, N.M., where scientists were developing the atomic bomb.

When Julius Rosenberg learned of this, he recruited his brother-in-law to gather information to pass on to Soviet agents. Greenglass complied, delivering notes from conversations with fellow workers about aspects of atomic research and a sketch of what he said was an implosion-type nuclear device.

Security at Los Alamos was so lax that Greenglass even slipped a cartridge for an exploding-wire detonator into his pocket and walked out the door with it.

The Rosenbergs turned all this over to Harry Gold, a courier for the spy ring, who then passed it on to Anatoly A. Yakovlev, the Soviet Union’s vice-consul in New York City.

Following the arrest of a German-born physicist, Klaus Fuchs, who had also worked on the Manhattan Project, a series of revelations led, in June 1950, to the arrest of Julius Rosenberg as an atomic spy. Ethel’s arrest followed in July. Evidence suggests that Ethel was held mainly in an effort to force her husband to reveal further names and information. This never happened.

On March 29, 1951, the Rosenbergs were convicted of treason. Following failed pleas for clemency to President Dwight Eisenhower, they were executed two years later.

The constitutionality and applicability of the Espionage Act of 1917, under which the Rosenbergs were tried, as well as the impartiality of the trial judge, Irving R. Kaufman, were key issues during the appeals process.

Because the defendants were Jewish, as was Emanuel Bloch, their defence attorney, many American Jews feared the case would incite a wave of anti-Semitism — though both Judge Kaufman and the chief prosecutor, Irving Saypol, also were Jewish, as was Roy Cohn, who was part of the government’s legal team. (After the Rosenberg trial, Cohn was appointed as Senator Joseph McCarthy’s chief legal counsel.)

So, although a number of leftist Jewish organizations protested the verdict, most were conspicuously silent. Both Rosenbergs, as well as the other defendants, were Communists. Public condemnation of them, a general identification of Jews with left-wing causes, and McCarthyism made many Jews fear that their own loyalty was under scrutiny. Some Jewish leaders, including those of the American Jewish Committee, publicly endorsed the guilty verdict.

The global political context was also a clear factor.

The United States was involved in the Korean War, and engaged in a worldwide ideological struggle with the Soviet Union. In pronouncing their death sentence, Judge Kaufman described the Rosenbergs’ crime as “worse than murder.” During the trial, Saypol stated that, by typing up the description of the atomic secrets, Ethel Rosenberg “struck the keys, blow by blow, against her own country in the interests of the Soviets.”

Kaufman, who died in 1992, later complained that he continued to be harassed for having imposed the sentences. “I’m sure the decision plagued him to his last days,” Professor Yale Kamisar of the University of Michigan Law School told the New York Times on Feb. 3, 1992.

In his 2004 book America on Trial, Alan Dershowitz, the Harvard law professor, citing a 1986 conversation with Rosenberg prosecutor Roy Cohn, wrote that Cohn “proudly told me shortly before his death that the government had ‘manufactured’ evidence against the Rosenbergs, because they knew Julius was the head of a spy ring. They had learned this from bugging a foreign embassy, but they could not disclose any information learned from the bug, so they made up some evidence in order to prove what they already knew. In the process, they also made up the case against Ethel Rosenberg.”

In the years after the Rosenbergs’ executions, there was significant debate about their guilt. The two were frequently regarded as victims of cynical and vindictive government officials. But the release in the 1990s of the Soviet intelligence information known as the Venona transcripts confirmed the Rosenbergs’ involvement in a spy ring.

Still, although Julius Rosenberg was guilty, Ethel’s role in any conspiracy was tiny at most. Morton Sobell told the New York Times on Sept. 11, 2008 that she was aware of her husband’s activity but did not directly participate in it. “She knew what he was doing,” he told journalist Sam Roberts, “but what was she guilty of? Of being Julius’ wife.”

As well, the importance of Greenglass’ stolen material would later be contested. Both Soviet and American experts have ascertained that it was of little value.

So, while Julius Rosenberg did break the Espionage Act of 1917 by passing intelligence on to the Russians, by far the greater crime was to kill him and his wife. They were the first, and only, American civilians ever executed for espionage in peacetime.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.