France has taken another step forward in acknowledging its role in the Holocaust. On Dec. 5, it announced it had established a fund to compensate Jews who had been deported to German concentration camps on French trains belonging to the state railway company, SNCF.

By all estimates, SNCF, under pressure from Germany, sent some 76,000 Jews to camps in Nazi-occupied Poland in 67 separate transports.

The $60 million fund, which is to be managed by the United States, will affect thousands of Holocaust survivors, who will now have to drop all claims against SNCF.

SNCF did not sign the agreement, but the company has agreed to contribute $4 million over the next five years to set up Holocaust museums and memorials in France, Israel and the United States.

Stuart Eizenstat, a U.S. official who worked on this file, described the accord as “a measure of justice for the harms of one of history’s darkest eras.” He was referring, of course, to the Vichy period, when a fascist regime headed by Marshall Henri Philippe Petain marginalized and demonized the Jewish community and collaborated with Germany in deporting one-quarter of the Jews of France.

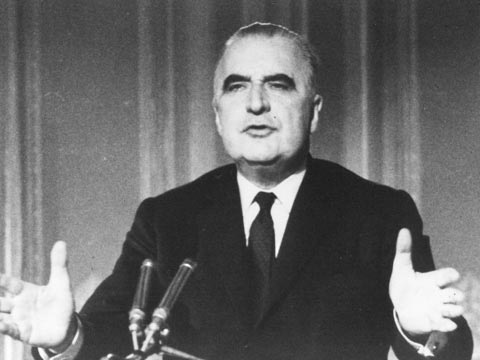

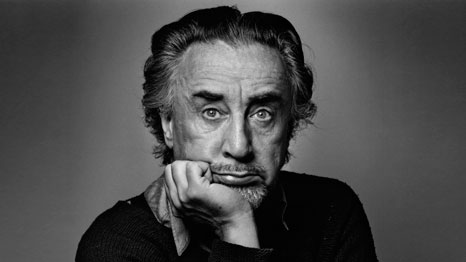

For years, postwar French governments were loathe to come to terms with Vichy’s crimes. In 1969, when French President Georges Pompidou was informed that Marcel Ophuls’ new documentary about Vichy, The Sorrow and the Pity, would shortly be broadcast on French state TV, he grew angry.

Ophuls’ film, ground-breaking and myth-shattering in every respect, was a challenge to French nationalists like Pompidou, who fervently believed that the Vichy interregnum was neither representative of France nor of its revolutionary ideals. Far from buying into that rose-colored version of events so favored by the French political elite of the day, the film documented the shameful policies of a craven antisemitic regime that rolled back more than a century’s worth of progress in the emancipation of Jews.

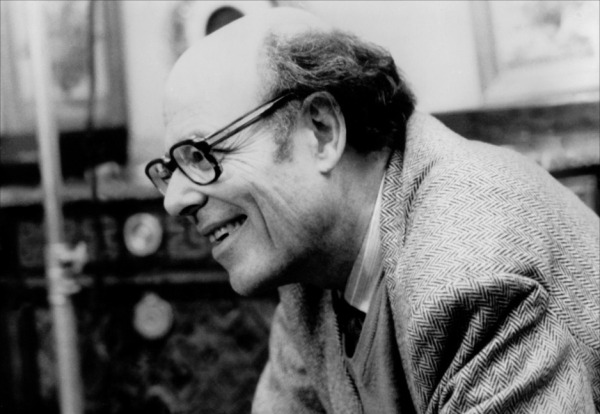

In effect, Ophuls, an American born in France, exploded the cherished myth that French men and women had joined the resistance movement in droves and had acted honorably during the four-year Nazi occupation.

Aghast that Ophuls had reopened old wounds, Pompidou banned The Sorrow and the Pity from the airwaves, certain that the “unity” of France was more important than regurgitating the past. But in banning the movie, which has since been screened on French television, Pompidou inadvertently ignited a debate on France’s conduct during the Nazi occupation.

Since this incident, France has tried to make amends.

The French government has paid restitution in the amount of about $6 billion to Holocaust survivors and their heirs, compared to the $85 billion Germany has already doled out. France has brought major and minor war criminals to justice. And in a significant gesture of contrition in 1995 to mark the 53rd anniversary of a French police roundup of Jews in Paris, President Jacques Chirac declared, “Yes, the criminal folly of the (Nazi) occupiers was assisted by the French people. These dark hours tarnish our history forever.”

In retrospect, France began the lengthy process of plumbing its ugly past after regaining its sovereignty in 1944. In a wave of vengeance, French resistance fighters and aggrieved individuals killed upwards of 10,000 collaborators. Petain was sentenced to death, though his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. Pierre Laval, the Vichy prime minister, was executed, as were some 2,000 former officials who had been found guilty of treason.

All told, 300,000 French nationals were tried in the wake of the war. The accused included Louis Darquier de Pellepoix, the director of the national commission in charge of Jewish matters; Maurice Gabolde, a minister of justice; Jean Angeli, the regional prefect in Lyons; Pierre Boreo, an official implicated in the murder of Georges Mandel, a former cabinet minister, and Yves Bouthiller, a finance minister.

Toward the close of the 1940s, as the Cold War intensified, the majority of convicted war criminals were released from prison and rehabilitated. In a word, France wanted closure.

Several top-ranking Vichy officials managed to elude justice. One such person, Maurice Papon, signed orders that resulted in the deportation 1,600 Jews between 1942 to 1944. Yet after the war, he enjoyed a civil service career as chief of the Paris police force and budget minister in Valery Giscard d’Estaing’s government.

Aside from rescinding Vichy’s anti-Jewish legislation, France returned Jewish property that had been expropriated or sold under duress below market value. And in another conciliatory gesture, the French government permitted Holocaust survivors from countries such as Poland and Romania to settle in France and become citizens.

Nonetheless, the Holocaust was not an issue that French politicians from the 1950s onwards generally cared to discuss. For example, Charles de Gaulle, the first president of the Fifth Republic, sought to reshape the past so that the glories of the French resistance movement would drown out the ignominy of the Vichy era.

Still, memories of the Holocaust bubbled beneath the surface. Romain Gary and Andre Schwarz Bart, two of the winners of France’s most prestigious literary award, the Prix Goncourt, wrote searing novels about the Holocaust. American historian Robert Paxton’s book, Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, aroused interest in the Holocaust as well.

The 1968 students’ revolt and the dedication of a memorial at the Drancy transit camp in 1976 stirred debate about the Holocaust, too. Since then, a succession of Holocaust monuments have been built in France.

To some observers, one of the turning points in French awareness of the Holocaust took place in 1978, when Serge Klarsfeld, a child survivor and Nazi hunter, mounted an exhibit in Paris on Vichy’s maltreatment of Jews.

From the late 1980s onward, France prosecuted war criminals such as Paul Touvier and Klaus Barbie. The French government also created the Matteoli Commission (1997) and the Dray Commission (2000), both of which rigorously reexamined the complicated issue of confiscated Jewish property.

And now that a reparation fund has been created to compensate survivors and their heirs for SNCF’s complicity in the deportation of Jews, France has begun settling one of the last outstanding problems related to the Holocaust.

This appeared in the National Post.