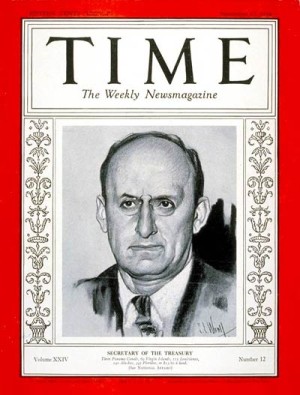

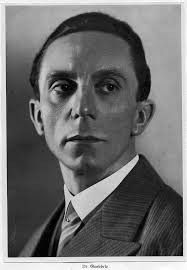

On Aug. 25, 1938, Der Angriff — a Nazi newspaper published in Berlin under the auspices of Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels — described Henry Morgenthau Jr., the U.S. secretary of the treasury, as “the real chief of a wide Judeo-Bolshevik conspiracy” against Germany.

The antipathy was mutual.

Morgenthau, the sole Jew in President Franklin Roosevelt’s cabinet, hated Adolf Hitler’s fascist regime with an all-consuming passion. During World War II, he played a pivotal role in the Allied victory over Germany.

The scion of a wealthy German-Jewish family and the most powerful American Jew of his day, he’s the subject of Peter Moreira’s thoughtful book, The Jew Who Defeated Hitler (Prometheus Books), which examines his contributions to the American economy at a particularly perilous time and his efforts to rescue Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe.

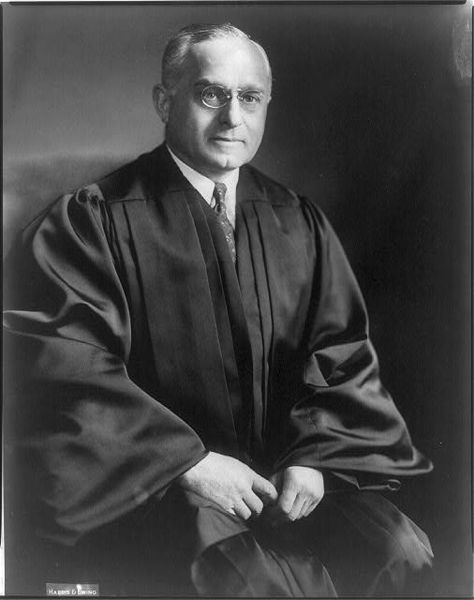

Morgenthau was not Roosevelt’s only Jewish confidant. The president surrounded himself with Jews, from the financier Bernard Baruch to the Supreme Court judge Felix Frankfurter. “In one of history’s cruel coincidences, Jews gained unprecedented political power in the United States just as the Nazis were coming to power in Germany,” writes Moreira.

Bigoted Americans were none too pleased by Roosevelt’s friendship with Jews, commonly referring to his Depression-era New Deal recovery program as “the Jew Deal.”

Keenly aware of the explicit antisemitism that blighted 1930s America, Morgenthau rarely raised the issue of persecuted European Jews. “He and his wife often worried about the public impression that he would create by identifying himself with Jewish issues or making statements against the Nazis,” says Moreira.

But as news got out that Germany was systematically exterminating Jews, he abandoned his reticence and urged Roosevelt to mount a rescue effort. Morgenthau’s views carried weight due to his pivotal position in government, especially after the entry of the United States into the war following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Moreira claims that a turning point in his relationship with Jewish issues came after Rabbi Stephen Wise, a Jewish community leader, gave him a graphic briefing about the Holocaust. Their meeting, Morgenthau would later say, changed his life.

Much to his dismay, Morgenthau learned that certain senior officials in the U.S. State Department were blocking efforts to help Jews. Morgenthau, nonetheless, pressed on, and Moriera elaborates on this point at length.

In January 1944, Morgenthau presented Roosevelt with a report claiming that the State Department had utterly failed to “prevent the extermination of Jews in German-controlled Europe.” As a result, Roosevelt authorized the establishment of the War Refugee Board. Headed by government official John Pehle, its objective was to save what was still left of European Jewry, particularly in Hungary. From that point onward, Morgenthau openly identified himself with that cause.

As the war wound down, Morgenthau, his hatred of Nazi Germany undiminished, became deeply involved in discussions on Germany’s postwar future. A report he submitted to the White House, known as the Morgenthau Plan, called for the de-industrialization and dismemberment of Germany.

Initially, Roosevelt supported it. But as opposition to it mounted, he wavered. Goebbels claimed that Morgenthau’s scheme was proof that Jews were trying to destroy Germany. Roosevelt’s successor, Harry Truman, was not keen about it either. So it was never implemented. Moreira himself thinks it was a “bad” idea.

In assessing Morgenthau’s pre-war record, Moreira gives him rather low marks for his management of the economy. But he offers high praise for his handling of the wartime economy and for his efforts to supply Britain with arms under the lend-lease program.

And as Moreira points out, Morgenthau’s work on behalf of imperilled European Jews was exemplary. The War Refugee Board is estimated to have saved about 200,000 Jews. “It was created tragically late in the war, but it is impossible to overstate in human terms the good it performed,” writes Moreira in this workmanlike book.