It was historically and morally necessary to publish a critical, annotated version of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf (My Struggle), a prominent German historian said recently.

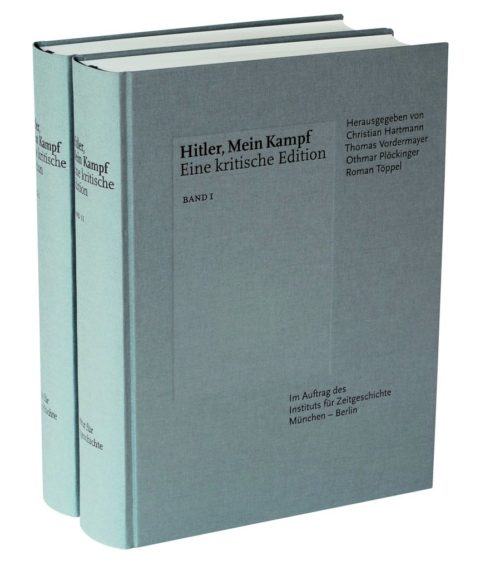

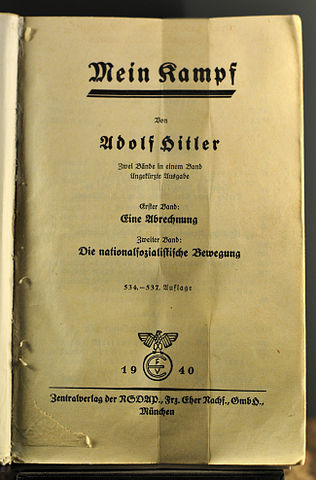

The two-volume edition was published by the Institute for Contemporary History in Munich last January with a print run of 4,000 copies and was immediately snapped up by buyers in Germany.

“We don’t need myths about Mein Kampf,” said Andreas Wirsching, the director of the institute and a professor of modern history at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich. “What was needed was transparency.”

Wirsching made his comments on October 28 in a lecture at the University of Toronto’s Munk School for Global Affairs. The event was sponsored by the consulate of the Federal Republic of Germany, the Centre for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies, the Institute for Contemporary History and the Joint Initiative in German and European Studies.

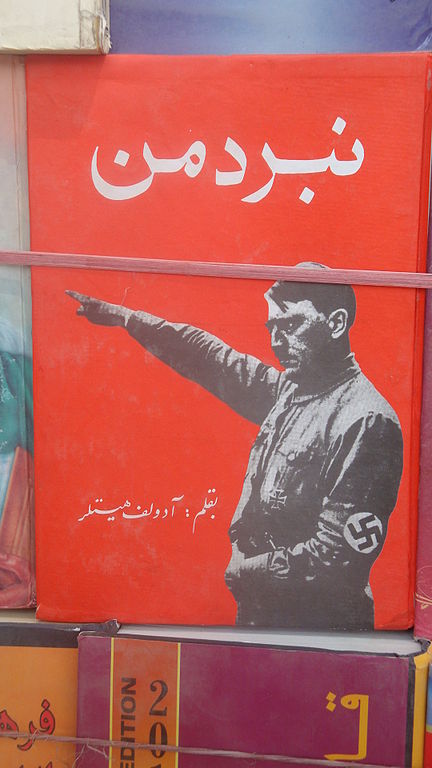

The new edition of Mein Kampf was the first to be published in Germany since the end of World War II. Old copies, however, could be purchased in used book stores. And with the dawning of the digital age, Mein Kampf could easily be downloaded.

Following Germany’s surrender in 1945, Mein Kampf was banned by Allied occupation forces and its copyright transferred to the state of Bavaria. When the copyright expired late last year, the institute was legally free to publish Hitler’s manifesto in its original German.

“This became the magical date,” said Wirsching.

The institute, which has published scores of studies on the 12-year Nazi era, began work on the 1,948-page edition in 2009.

To Wirsching, Mein Kampf is the single most important source of Hitler’s thoughts, ideas and intentions. Hitler originally wanted to call his book Four and a Half Years of Struggle Against Lies, Stupidity and Cowardice, but his publisher persuaded him to shorten the title.

Hitler — a World War I veteran — wrote it while in Landsberg prison. He was arrested after participating in a failed putsch in Munich to overthrow the Bavarian government.

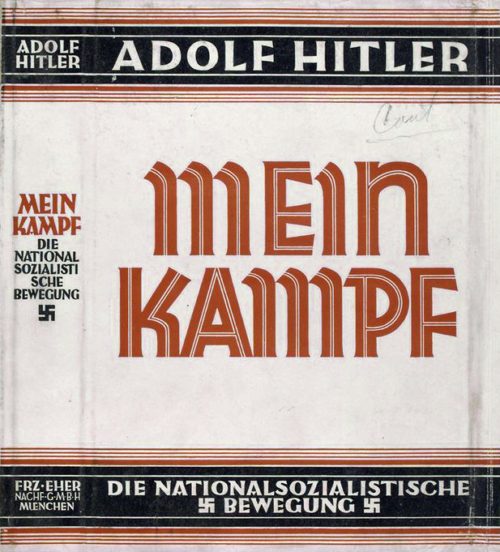

Volume one, which is autobiographical, appeared in 1925. Volume two, setting out his political and ideological program, was published a year later. Among the topics he addressed were Germany’s need for “living space” in Eastern Europe, euthanasia and the “Jewish menace.”

In one typical passage about Jews, he writes: “With satanic joy in his face, the black-haired Jewish youth lurks in wait for the unsuspecting girl whom he defiles with his blood, thus stealing her from her people. With every means he tries to destroy the racial foundations of the people he has set out to subjugate. Just as he himself systematically ruins women and girls, he does not shrink back from pulling down the blood barriers for others, even on a large scale.”

Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s propaganda minister, described Mein Kampf as the “gospel of a new era,” though he had reservations about its turgid style. Still others called it the “bible” of the Nazi movement, which governed Germany from 1933 to 1945.

By the end of Hitler’s first year in office as chancellor, it had become a bestseller, having sold 1.5 million copies. By 1945, 12 million copies in 18 languages, including Arabic, had been bought. The royalties made Hitler wealthy.

The edition published by the institute contains the original text, plus more than 3,500 annotations intended to place Hitler’s ideas in their proper historical perspective. Hitler’s lies, half-truths and flights of propaganda are leavened by commentary written by a team of historians, said Wirsching.

There was never any intention to publish Mein Kampf without these commentaries, he said.

The index runs to about 80 pages and is useful because very few people would bother reading Mein Kampf from beginning to end, he noted.

Wirsching said he and his colleagues were concerned by what the response of Holocaust survivors and the Jewish community would be. “We wanted to respect their dignity,” he said.

As it happened, the reaction was mixed. The attitude of Charlotte Knobloch, a Jewish community leader in Munich, seemed indicative of opinion among Jewish leaders. Initially, Knobloch supported the project, but changed her mind after visiting Israel in 2013, he said.