John Kerry, the U.S. secretary of state, had a clear message for Egypt, a key Arab ally, when he visited Cairo on August 1.

Warning the authoritarian Egyptian government that it could lose its battle against domestic terrorism unless it shows far more respect for human rights, he said, “The success of our fight against terrorism depends on building trust between the authorities and the public.”

Kerry’s host, Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry, deftly deflected the criticism, claiming that Egypt is trying to strike a better balance between maintaining law and order and protecting human rights.

Ever since Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi seized power from his democratically elected predecessor, Mohammed Morsi, in a coup two years ago, Egypt has moved increasingly further away from Western-style democratic norms.

Since Morsi’s ouster and imprisonment, and the killing of more than 1,000 of his supporters in raging street battles, Egypt has been convulsed by an Islamic fundamentalist rebellion that has claimed the lives of hundreds of soldiers and officials and disrupted the tourist trade, a pillar of the Egyptian economy.

The revolt has been most keenly felt in the northern Sinai Peninsula, where Sinai Province, an Islamic State affiliate, has ruthlessly attacked administrative and military sites.

In response, Sisi’s secular nationalist regime has banned Mori’s party, the Muslim Brotherhood, detained about 10,000 people suspected of being subversives and rioters, defanged parliament and drafted draconian laws that have stripped Egyptians of their basic freedoms.

The new regulations ban demonstrations, remove limits on the detention of suspects awaiting trial, impose restrictions on the media and restrict the funding of non-governmental organizations. Not since the days of the late Gamal Abdel Nasser, who ruled with an iron hand from 1954 to 1970, has Egypt been in the grip of such rampant authoritarianism.

Sisi — the former defence minister and chief of staff of the armed forces — has turned back the clock. Acting without parliamentary oversight or consent, he has erased the gains won by demonstrators during the 18-day Arab Spring rebellion in the winter of 2011, when Hosni Mubarak, the long-serving president, was unseated by the armed forces.

Since then, Sisi has squelched all forms of dissent, whether from the left, right or center, and restored the status quo ante. In short, Egypt is broadly back to where it was politically before 2011. As a result, disillusionment and bitterness on a mass scale have set in, creating the conditions for yet more dissension and rebellion.

At first, the United States backed Mubarak’s efforts to crush the insurrection. But after three weeks of nation-wide rioting, which caused the deaths of some 800 Egyptians, the Obama administration essentially abandoned him to his fate, hoping that the interim military administration would stabilize Egypt.

Washington recognized the Morsi regime when it swept into power in 2012. A little more than a year later, the Morsi era ended abruptly in a violent spasm of blood and gore, prompting the United States to lambaste Sisi’s brutal methods and reduce military aid.

But in a U-turn prompted by concerns that Egypt might drift away from its alliance with the United States, fail to defeat local jihadists and renege on its 1979 peace treaty with Israel, Washington began to rebuild relations with Sisi.

In this spirit, Kerry visited Cairo last March to assure Sisi that the United States’ concerns over human rights infringements would not trump its strategic dialogue and security cooperation with Egypt.

On his latest trip this week, Kerry made good on his promise. The United States delivered eight American-manufactured F-16 fighter jets whose delivery had been suspended following Morsi’s ouster, and Kerry informed his Egyptian interlocutors that the United States intends to resume joint military exercises with Egypt.

Nonetheless, Kerry brought up the human rights issue, spurred by a report that the Obama administration submitted to the U.S. Congress three months ago.

The report states that “the overall trajectory for rights and democracy has been negative. A series of executive initiatives, new laws and judicial actions severely restrict freedom of the press, freedom of association, freedom of peaceful assembly and due process, and they undermine prospects for democratic governance.”

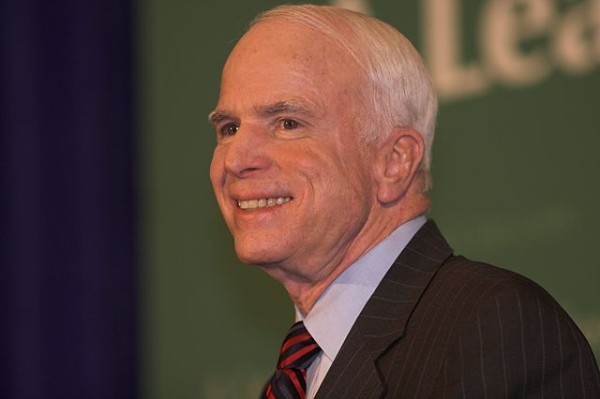

More recently, a bipartisan group of six U.S. senators, led by Democrat Ben Cardin of Maryland and Republican John McCain of Arizona, released a letter warning that the suppression of “peaceful and legitimate avenues for dissent” could well fuel “violent extremism” and increase “the likelihood of long-term instability.”

It’s highly questionable whether Sisi will take these considerations seriously. Preoccupied by the Islamist rebellion, which consumes Egypt and threatens his political survival, he has no intention of observing the niceties of democracy. In the past month alone, Sisi has vowed to enact legislation to speed up the trials of terrorists and to exert greater control over the media.

Clearly, Sisi had adopted a hard line on terrorism and internal dissent and will not be diverted from this path even by his closest foreign allies.