In 2004, I co-edited a book, De Facto States: The Quest for Sovereignty, that was to include a chapter on Iraqi Kurdistan. The person asked to write it didn’t come through, though, so it wasn’t included.

Today such an article would be an absolute necessity. It’s been a long time coming, but on September 25 the Kurds in northern Iraq will finally be voting in a referendum on independence.

In February 2016, Masoud Barzani, president of the Kurdistan Autonomous Region, announced his desire to hold a referendum among Iraqi Kurds on the issue of independence, despite opposition from its neighbors as well as the United States.

Those who follow events in the Middle East know that the Kurds, at least 30 million in number, are the largest ethnic group in the world without their own country, even though one was promised them as far back as the end of World War I.

They are spread across the region, mainly in Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey, and have fought for a state of their own at one time or another in all of these countries.

But only in Iraq, where they have enjoyed limited self-government since the Gulf War in 1991, when the United States enforced a no-fly zone across the north, have they had a realistic chance to acquire it. Indeed, the area they govern has increased since the Islamic State drove the Iraqi army out of northern Iraq in 2014.

They now control around a fifth of Iraq’s territory, including land they have long claimed is theirs but which was Arabized under Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein. It includes the disputed city of Kirkuk.

Their red, white and green flag flies everywhere in the region, including Kirkuk, whereas the Iraqi one is absent.

While the rest of Iraq has for years been beset by violence, the Kurdistan Region, with its population of eight million, has developed economically, matured politically, and gained international recognition as part of a federal Iraqi state in 2005.

Their leaders say their region increasingly makes sense as an economic unit, especially if they were to enjoy the proceeds of the oilfields around Kirkuk.

Before the elimination of Saddam Hussein, the Kurds in Iraq were the victims of mass murder and ethnic cleansing, which peaked in the late 1980s when Saddam slaughtered some 200,000 of them, razed thousands of villages and, most notoriously, used chemical weapons, most notably at Halabja in 1988, where 5,000 died.

The Kurds have long said that they have “no friends but the mountains,” where they have often fled for sanctuary.

In 1992, the two major political parties in the region, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), established the autonomous regional government.

The two parties have long contended for power, including a four-year armed struggle in the 1990s. The capital, Erbil, is the stronghold of the KDP, led by the Barzani clan. The current prime minister, Nechirvan Barzani, is a nephew of the region’s president, Masoud Barzani. The latter has been president of the Kurdistan region since 2005, as well as leader of the KDP since 1979.

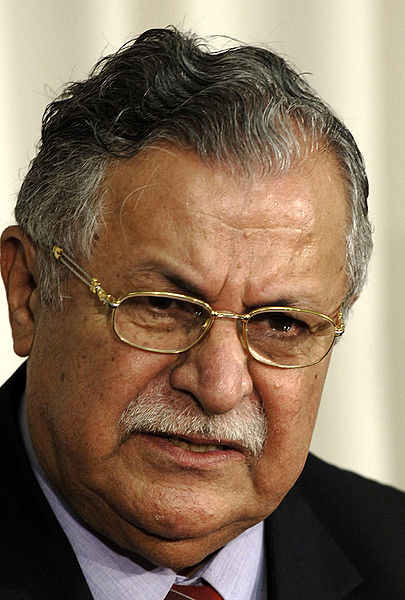

The weaker PUK is run by the Talabanis, whose leader, Jalal Talabani, is a former president of Iraq. His son, Qubad, has been the deputy prime minister since 2005. They dominate the region around the city of Sulaimaniyya.

Not surprisingly, the Baghdad government opposes the referendum and has said it would never give up its claim to Kirkuk. The Imam Ali Division, an armed Shiite faction in Iraq backed by Iran, warned that it will attack Kirkuk if the city is annexed to Kurdistan.

On September 16, Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi cautioned the Kurds that “if you challenge the borders of Iraq and the borders of the region, this is a public invitation to the countries in the region to violate Iraqi borders as well, which is a very dangerous escalation.”

A Kurdish reform group called the Movement for Change Party, or Goran, which split off from the PUK in 2009, also is hesitant and has refused to join the KDP-led referendum committee.

Washington, concerned that the vote would hobble the fight against the Islamic State, also views it as a bad precedent and as a destabilizing force in the region, and has threatened to suspend aid to the Kurds.

The White House has called for the Kurdish region to abandon the referendum “and enter into serious and sustained dialogue with Baghdad.”

The governments of Iran, Turkey and Syria dislike the idea of an independent Kurdistan breaking away from Iraq, since the Kurds in those countries might wish to join them in a greater Kurdistan.

Turkey has called the referendum a “historic mistake,” warning that Kurdish Iraq would “pay a price” if it went through with the vote. Ankara has for years been battling Kurdish separatists in the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK.

In Syria, embroiled in civil war, the People’s Protection Units (YPG), a Kurdish militia that is part of the Syrian Democratic Forces, has been carving out an autonomous region known as Rojava on the border with Turkey.

On the other hand, Israel, which has historically been favorable to Kurdish aspirations and in the past supported their fight for independence, welcomed the move.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on September 13 announced that he “supports the legitimate efforts of the Kurdish people to achieve their own state.”

In turn, a number of Turkish media outlets supportive of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan have published news reports claiming that Kurdish groups entered into a secret deal with Israel to gain their independence by resettling Jews to the region.

Stories appearing in the Turkish newspapers Yenia Akit and Aksam alleged that President Barzani agreed to welcome some 200,000 Israeli Jews of Kurdish origin back to Kurdistan if Israel would back his bid for Kurdish statehood

Iran, too, claims Israel is behind the move. The independence referendum is an age-old dream “to create another Israel in the region,” Ayatollah Ahmad Khatami, a senior Iranian cleric, told a gathering of worshipers in Tehran on September 15.

He expressed the hope that Kurds would come to their senses and give up the Israeli plot.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.