The strategic relationship between the “mosque” and the “market” is explored by Aisha Ahmad in her bracingly original book, Jihad & Co.: Black Markets and Islamist Power, published by Oxford University Press.

Ahmad, an assistant professor in the department of political science at the University of Toronto, focuses her attention on unstable and ungovernable parts of the Middle East and Africa where “profit-driven business elites” and “ideologically-motivated Islamists,” otherwise known as jihadists, have formed mutually-beneficial alliances and created what she describes as “proto-states.”

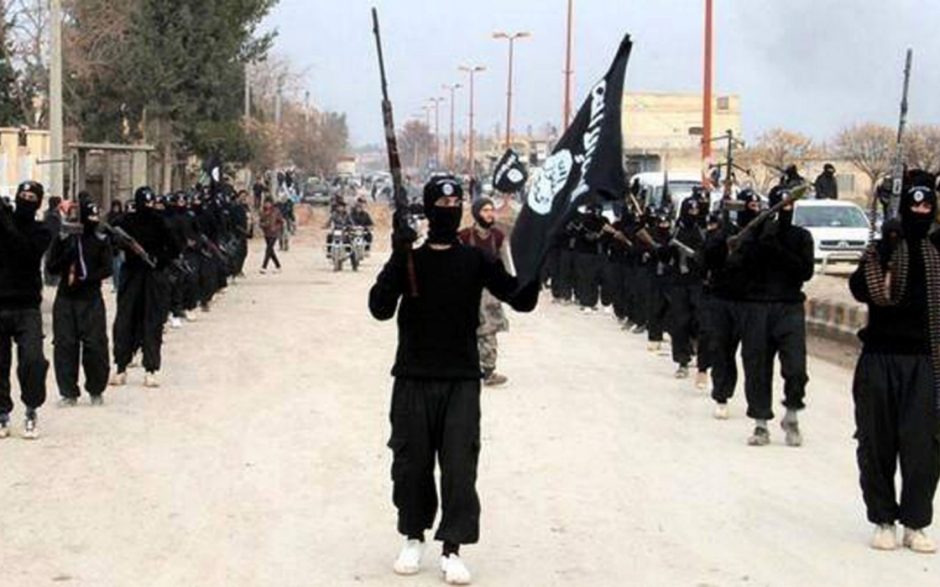

The countries she includes in her survey range from Syria and Iraq to Somalia and Afghanistan, where radical Islamic groups such as the Islamic State and the Taliban have asserted themselves.

Ahmad defines a proto-state as “a nascent political entity that features a primitive near-monopolization of force, consolidation of territorial control within or across state borders, a hierarchical religious-political leadership with repressive capabilities over its populations, and rudimentary governing institutions to enforce its rule of law.”

In her estimation, the proto-state is more than a fiefdom dominated by a single warlord. It is “an emergent polity that can perform many but not all of the normal functions of a sovereign state.” The failure of the post-colonial sovereign state system, she says, has contributed to the rise of proto-states.

“Across the Muslim world,” she writes, “the proto-state acts as a practical twenty-first century political alternative to the contemporary failure of both nationalism and tribalism. This political entity is a fundamental rejection of the secular state construct that seeks to redraw the world map to reflect a new configuration of emergent Islamist polities.”

Challenging the conventional wisdom that the success of these entities is dependent on religious conviction or tribal networks, Ahmad claims that financial considerations play a key role in the formation of marriages of convenience between the “mosque” and the “market.”

As an example, she cites Somalia, a failed state torn asunder by lawlessness and social fragmentation. Ruled by Mohammed Barre for 22 years, his authoritarian regime was successively propped up by the Soviet Union and the United States during the Cold War. As a result of economic mismanagement and political divisiveness, his government went bankrupt and collapsed, ushering in a civil war along tribal lines.

In this high-risk, low-trust environment bereft of functioning government institutions, rich Somalian entrepreneurs turned to Islam — armed Salafist militias and mullahs — to build trust, lower costs and increase access to markets in nearby Gulf states.

“The Somali business class therefore took on a Salafi identity, and those elites who demonstrated the greatest Islamic credentials became the most wealthy and powerful,” Ahmad explains. “While the adoption of a Salafi identity within the business community may have been driven by rational self-interest, in the long run, it also had a transformative effect on the identity of the business community as a whole.”

Northwest Africa — Mali, Algeria, Mauritania and Niger — was also affected by this process, as were certain areas of Pakistan.

In Afghanistan, the Taliban courted the support of the business class by clearing trade routes. “Unlike the rapacious ethnic warlords, the Taliban appeared to be a low-cost solution to the high costs of civil war,” she notes. “Rallying behind the new Islamist movement, members of the business class helped turn the Taliban into a surprisingly powerful new contender, which quickly ousted the well-established ethnic warlords on the battlefield.”

Islamic courts were equally successful in recruiting businessmen.

As she adds, Islamic State created “robust and institutionalized” jihadist proto-states in Syria and Iraq before its military defeat at the hands of the Syrian and Iraqi regimes, the Kurds and the United States and Russia.

In conclusion, Ahmad warns that jihadists cannot be eliminated by brute force alone: “The instruments of war — whether drone strikes or cruise missiles — do not resolve the humanitarian or political crises that justify their use.”

She recommends “less invasive political solutions,” which are “acutely warranted.” Whether she is right remains to be seen.