Should a genocidal killer be held in esteem? Should a school be named after him? Should a plaque in his honor be permitted to remain in the library of a major educational institution?

Of course not!

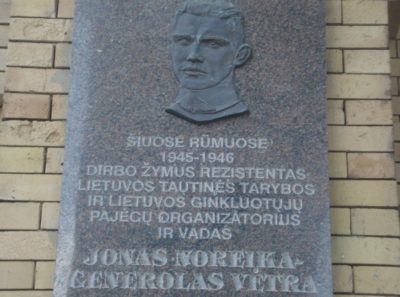

And yet this is precisely what happened in Lithuania when Jonas Noreika — a Nazi collaborator and an arch antisemite who organized pogroms during the German occupation — was accorded these honors.

Noreika, who was known as General Storm, was widely regarded as a national hero by innumerable Lithuanians by virtue of his anti-communist views and his resistance to the occupation of Lithuania by the Soviet Union in 1940 and again in 1945.

Yet his association with Nazi Germany and his virulent antisemitism, though not exactly a secret, were overlooked and tolerated by far too many Lithuanians.

Except his own granddaughter, Silvia Foti.

Foti, an American journalist who was raised in Chicago’s Marquette Park, the neighborhood with the largest Lithuanian population outside Lithuania, scandalized her community by courageously exposing Noreika as a war criminal in a recent edition of the on-line magazine Salon.

A few days ago, The New York Times ran a lengthy story about Noreika, thereby ensuring that his notoriety would reach a much greater readership, not only in the United States but overseas as well.

By her estimate, he sanctioned the murders of 2,000 Jews in Plungė, 5,500 Jews in Šiauliai and 7,000 Jews in Telšiai.

Having been responsible for exposing him, Foti, one can safely assume, has become a persona non-grata among Lithuanian nationalists, who believe she has unjustly besmirched his good name and reputation.

From my point of view, Foti should be commended for her bravery, persistence and thoroughness in “outing” Noreika and shedding more light on the Holocaust in Lithuania. The genocide in Lithuania devoured more than 90 percent of its pre-war Jewish population, the highest mortality rate in Nazi-occupied Europe.

I read Foti’s gripping piece in Salon and wish to reproduce excerpts. No one can tell the story better than Foti herself:

“Eighteen years ago, my dying mother asked me to continue working on a book about her father, Jonas Noreika, a famous Lithuanian World War II hero who fought the Communists. Once an opera singer, my mother had passionately devoted herself to this mission and had even gotten a PhD in literature to improve her literary skills. As a journalist, I agreed. I had no idea I was embarking on a project that would lead to a personal crisis, Holocaust denial and an official cover-up by the Lithuanian government.

Growing up in Marquette Park … I’d heard about how my grandfather died a martyr for the cause of Lithuania’s freedom at the hands of the KGB when he was just 37 years old. According to the family account, he led an uprising against the Communists and won our country back from them, only to have it snatched by the Germans. He became chairman of the northwestern part of the country during the German occupation. According to family lore, he had fought the Nazis and then been sent to a concentration camp in retaliation. He escaped that camp and returned to Vilnius to start a new rebellion against the Communists, had been caught, taken to the KGB prison and tortured … His nom de guerre was General Storm. It all seemed so romantic to me.

“That is the book I started to write. My mother had collected a trove of material that included 3,000 pages of KGB transcripts; 77 letters to my grandmother; a fairytale to my mother written from the Stutthof concentration camp; letters from family members about his childhood; and hundreds of newspaper and magazine articles.

“A few months into the project, I visited my dying grandmother, who lived a few blocks away. She asked me not to write the book about her husband. ‘Just let history lay,’ she whispered. I was stunned. ‘But I promised Mom,’ I said. She rolled over to face the wall. I didn’t take her request seriously; I thought she was simply giving me a pass because she knew how taxing the project was for my mother.

“In October 2000, after my grandmother died, my brother, Ray and I took the cremated remains of our mother and grandmother back to Lithuania to be buried, as they had wished. We were surprised by the outpouring of affection shown at their funeral in the Vilnius Cathedral, and especially astonished when President Landsbergis appeared with his wife to pay their respects to the widow, daughter and grandchildren of General Storm. Many at the funeral had asked, ‘What about the book on your grandfather?’ I answered, ‘I promised I would finish it.’ They patted my back, squeezed my arms and kissed my cheeks. ‘You’re such a good daughter. Our country needs heroes.’”

“From Vilnius, Ray and I travelled as honorary guests to Šukoniai, the northern town where our grandfather was born, to see the grammar school named after him. We were shown the modest building of white bricks and oak trim. The school director, a roly-poly man with dishevelled white hair, enthusiastically grabbed our hands, telling us how pleased he was that we had come to host the ceremony in homage to our grandfather.

“He had heard I was writing a book. I asked him, ‘How did you decide to name the school after our grandfather?’ Stroking his chin, he answered, ‘It was during a meeting of the County Board. We wanted to pick a new name instead of the Russian one we had. Your grandfather’s surfaced immediately.’ Then he pulled Ray and me aside so the others couldn’t hear. ‘I got a lot of grief at first when we picked his name. He was accused of being a Jew-killer.’

“Ray and I were aghast. Accused of being a Jew-killer? I looked around the room, at the teachers and the principal. Who were these people? Who was my mother? My grandmother? Who was I? My mind whirled: There must be some mistake. The director stroked my arm in reassurance. ‘I’m getting more support than ever over choosing your grandfather’s name. All of that is in the past.’

“Back in Chicago, I continued to sift through my mother’s material on my grandfather. I was unwilling to admit that this accusation could be true, but then I noticed a yellowing 32-page booklet titled, Hold your Head High, Lithuanian!!! In it, I came across a rant against Jews: ‘In the land of Klaipėda, the Lithuanians are being overthrown by the Germans, and in Greater Lithuania, the Jews are buying up all the farms on auction. . . . Once and for all: We won’t buy any products from Jews!’ It was written by my grandfather. My hands shook: I did not want a grandfather who was the author of this brochure.

“I strongly considered dropping the project, even if it meant breaking the promise to my mother. Years passed until I felt psychologically ready to continue the investigation, bracing myself for the horrifying possibility that my grandfather was indeed involved in killing Jews.

“In 2013 I spent seven weeks in Lithuania. I hired a Holocaust guide, Simon Dovidavičius, director of Sugihara House, a museum honoring Chiune Sugihara, who helped 6,000 Jews escape to Japan during WWII. We became an unlikely pair, investigating the life of my grandfather. I showed him all the monuments on my grandfather; he showed me pits of where Jews were buried because of my grandfather. I gave him the book published by the Genocide Museum stating my grandfather was a hero; he gave me Holocaust books stating my grandfather was a villain.

“Dovidavičius was the first to suggest that my grandfather conducted the initial akcija (action) during World War II before the Germans arrived. It coincided with Operation Barbarossa on June 22, 1941, when Hitler invaded Russia, the same day Lithuania began its uprising with the Germans against the Soviets, marking the start of a Holocaust there, where 95 percent of its 200,000 Jews were murdered, the highest percentage of any country in Europe. (About 3,000 Jews remain in Lithuania today.)

“Within three weeks, 2,000 Jews had been killed in Plungė, half the town’s population, and where my grandfather led the uprising. This preceded the January 1942 Wannsee Conference, when Nazi Germany decided to make mass-murder its state policy. Put in more chilling terms, Dovidavičius claimed that my grandfather, as captain, taught his Lithuanian soldiers how to exterminate Jews efficiently: how to sequester them, march them into the woods, force them to dig their own graves and shove them into pits after shooting them. My grandfather was a master educator.”

This is a searingly honesty and moving account of a granddaughter who could have conveniently chosen to ignore hard, cold, ugly facts, but who instead decided to confront them head-on.

So what now?

At the very least, the school in Noreika’s birthplace should be renamed and his name should be immediately removed from the library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences.

As Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu observed during a recent visit to Lithuania, this Baltic nation has taken “great steps to commemorate the victims of the Holocaust.”

But as the notorious Noreika case clearly illustrates, Lithuania has not finished its reckoning with the Holocaust.