Late last month, just minutes after Poland’s parliament enacted legislation removing a troublesome clause from its controversial Holocaust law, ratified by President Anderzej Duda last February, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his Polish counterpart, Mateusz Morawiecki, issued a joint declaration intended to defuse tensions between Israel and Poland.

In at least two respects, the declaration was historically correct. It pointed out that the widely-used expression “Polish death camps” was “blatantly erroneous” and it affirmed that the wartime Polish government-in-exile tried “to raise awareness” about the Holocaust.

Condemning “every single case of cruelty against Jews perpetrated by Poles” during the German occupation of Poland, the declaration acknowledged the “heroic acts of numerous Poles, especially the Righteous Among the Nations, who risked their lives to save Jewish people.”

With these bold assertions, the declaration ended Israel’s diplomatic row with Poland, an important ally in Eastern Europe. But critics condemned it on the grounds that it whitewashed the harsh behavior of some Poles toward Jews.

Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial/education center in Jerusalem, claimed it was riddled with “grave errors and deceptions.” However, its chief historian, Dina Porat, later said “we can live with” much of it.

The historian Yehuda Bauer, a renowned specialist in the Holocaust, lambasted it as a “betrayal” and accused the Israeli government of expediency by sacrificing the truth in pursuit of its “current economic, security and political interests.”

The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum warned it “does not secure a future for Holocaust education, scholarship and remembrance.”

In my opinion, the declaration underplayed the degree of Polish hostility toward Jews and the role Poles played as perpetrators. These points are underscored in a superb book I’m currently reading by Joshua D. Zimmerman. The Polish Underground and the Jews, 1939-1945 (Cambridge University Press) is a groundbreaking study of the relationship between the Home Army (Armia Krajowa, AK), the largest resistance force in Nazi-occupied Europe, and the Jews of Poland. Its revelations relating to Polish-Jewish relations are revealing, sobering and shocking.

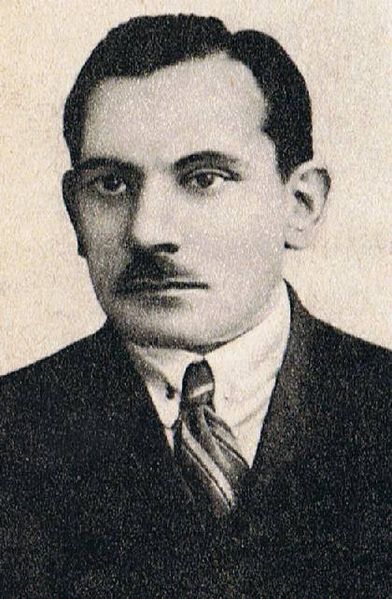

In 1940, Jan Karski, who had fought the Germans as a Polish solider in the opening round of World War II, was asked by Poland’s minister of information and documentation, Stanislaw Kot, to write a report on Polish-Jewish relations for the Polish government-in-exile in London.

In the German zone of occupation, Karski observed, the Polish attitude toward Jews is “overwhelmingly severe, often without pity.” He added, “This brings (the Polish population), to a certain extent, nearer to the Germans.” In eastern Poland, occupied by the Soviets until the 1941 German invasion of the Soviet Union, Poles “regard (Jews) as devoted to the Bolsheviks and — one can safely say — wait for the moment when they will be able to take revenge upon the Jews.” The majority of Poles, he wrote, “look forward to an opportunity for ‘repayment in blood.'”

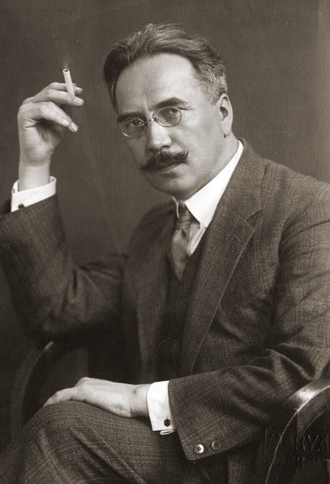

Stefan Rowecki, the chief commander of the Home Army from 1940 to 1943, sent this appraisal to the Polish government-in-exile in 1940: “Hatred against the Bolsheviks has led to a huge rise in the hatred of the peasant masses and the lower middle class towards the Jews. This is due to sympathy for the (Soviet) occupiers that is emerging from the Jewish masses (with the exception of the Zionists and the Bundists), as well as to the numerous examples of Jews taking part in the new Bolshevik administration and militias.”

Toward the close of 1940, the conservative prewar politician, Prince Janusz Radziwill, wrote that while Poles categorically disapproved of the German mistreatment of Jews, “it would nevertheless be a grave error to suppose that antisemitism among the Poles is a thing of the past.” Antisemitism, he went on to say, “still exists among all segments of society.”

In the same year, a Home Army report issued a glum report: “Many Poles are expressing satisfaction among themselves that the Jews are being removed … from Polish residential districts, official positions, the free professions, industry and commerce, but they do not allow themselves to display this outwardly in any form. This is because the people are shocked by the way the (German) measures are being carried out … For this reason, these people express quiet sympathy for the Jews and help them where possible, or at least do not make their difficult situation any worse.”

A minister in the Polish government-in-exile, Jan Stanczyk, delivered a speech in London in 1941 in which he claimed that Nazi-style racial antisemitism was “foreign to the psyche of the Polish nation.”

Yet in the wake of the Soviet withdrawal from eastern Poland, pogroms broke out in 66 towns in the northeastern sector of the country. These events prompted the Polish prime minister, Wladyslaw Sikorski, to release a stark statement: “The government places great emphasis on the necessity of warning (the Polish people) not to succumb to German incitement to participate in anti-Jewish actions …”

Another Home Army report, issued in the summer in 1941, concluded: “The mood of Polish society continues to be anti-Jewish …”

Tensions in eastern Poland were such that the Home Army reported, “The hostility of the Poles towards the Jews is so enormous that local Poles cannot imagine a return to normal relations with the Jews in the future. Even tolerating the Jews (may be problematic) — and this is not even referring to them returning to their former business establishments, which would result in intense rioting.”

Sikorski, in 1941, received a report from Rowecki attesting to the ill-will of Poles toward Jews: “Please accept it as a completely genuine fact that the overwhelming majority of the country is of an antisemitic orientation.”

Further reports in that year painted a dark picture of Polish perceptions of Jews.

As one report stated, “Latent antisemitism … is still rooted in Polish society and is exploited in German propaganda and in the right-wing (Polish) underground press … The most widespread opinion is that the Jewish problem will only be solved through the mass emigration of Jews from Poland … After taking away dominance in economic life from the Jews, relations in the future must be negotiated on the basis of full loyalty of the Jews to the Polish state.”

Kot, in a report, said he had assumed that the German persecution of Poles and Jews would have “brought these two peoples, heretofore alien to one another, closer together.” But “the very opposite is nonetheless the case,” he pointed out.

Kot also wrote, “Polish society is terrified of excessive Jewish influence. It is afraid that the need to import foreign capital into a decimated Poland would give the international financial Israelite magnates excessive power in the country, and that this might, in turn, enchain the country to ‘an economic Jewish slavery.'” In conclusion, he said that the “Jewish question” is still as sharp as ever and has “become significantly inflamed.”

Sikorski, in 1942, maintained that Poland “undoubtedly respects the freedom and the civil rights of all citizens faithful to the Republic regardless of nationality, religion or race.”

But, as a succession of Home Army reports indicated, a large proportion of Poles were unfavorably disposed toward Jews, contributing to the abysmal nature of Polish-Jewish relations.