Cynically portrayed by Nazi Germany as a “reeducation center,” the Sachsenhausen concentration camp was a synonym for unbridled state-sponsored terror. Although it was not an extermination camp, like Treblinka, it consumed the lives of about 50,000 people from 1936 to 1945.

Now a memorial and museum, Sachsenhausen was not the first concentration camp built on German soil, but was rather a template of things to come. Forty kilometres north of Berlin, near the pleasant suburb of Oranienburg, it was a prototype in the Nazi terror system.

Dachau, close to Munich, was the first Nazi concentration camp, having been opened two months after Adolf Hitler’s accession as Germany’s chancellor in January 1933. But while Dachau was constructed on the site of a former arms factory, Sachsenhausen was the first concentration camp to be erected from scratch.

In terms of its design and treatment of prisoners, Sachsenehausen set a new standard of brutality.

Shaped in the form of an equilateral triangle, with a circular roll call area close to the main gate festooned with the infamous slogan Arbeit Macht Frei, Sachsenhausen was indeed unique.

The administrative center of all German concentration camps was located in Oranienburg. Sachsenhausen itself was a training center for SS officers assigned to administer camps such as Bergen-Belsen and Buchenwald.

Ironically, it was inaugurated in the year Germany hosted the summer Olympic Games and launched a charm offensive to deflect attention away from its persecution of its Jewish citizens.

Sachsenhausen absorbed political prisoners, homosexuals, antisocial types, Jehovah Witnesses, Soviet prisoners of war and, of course, Jews.

Julius Leber, a Social Democratic Party leader, was held here, as were the cleric Martin Niemoller and the anti-Nazi activist Hans von Dohnanyi. German army officers implicated in the July 1944 assassination plot against Hitler were imprisoned here, including Gottfried von Bismarck-Schonhausen, a grandson of the 19th century German chancellor.

Kurt Schnuschnigg, one of Austria’s last chancellors before its annexation by Germany, was a prisoner in Sachsenhausen, as was Paul Reynaud, the former prime minister of France. Joseph Stalin’s eldest son and a Red Army POW, Yaakov Dzhugashvili, died here in 1943.

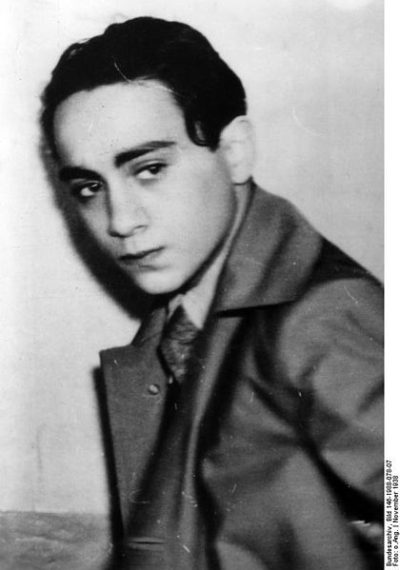

Herschel Grynszpan, the young Polish Jew who fatally shot a German diplomat in Paris and precipitated Kristallnacht in November 1938, was dispatched to Sachsenhausen as well.

Altogether, some 200,000 people passed through its gates, of whom about 40,000 were Jewish.

The first batch of 6,000 Jews arrived shortly after the 1938 pogrom, which heralded the end of Germany’s Jewish community. Later, Polish Jews living in Germany were sent there. In October 1942, a batch of Jewish inmates was transported from here to the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp.

Among its Jewish prisoners were 140 counterfeiters forced to forge U.S. dollars and British pound notes for a Nazi scheme to undermine the economies of the United States and Britain.

Whether Jewish or Christian, the inmates of Sachsenhausen were treated with the utmost callousness and cruelty. Upwards of 30,000 prisoners died of malnutrition, disease and exhaustion. More than 10,000 Soviet POWs, plus a much smaller group of Dutch resistance fighters, were shot. Thousands of prisoners died after being subjected to gruesome medical experiments.

To dispose of the corpses, the Nazis built a crematorium in 1940. When the camp’s mortality rate rose, they added a bigger crematorium two years later. Another addition, in 1943, was small gas chamber used to test the technology.

Sachsenhausen was evacuated in April 1945 as the Red Army advanced on Oranienburg. The Nazis burned incriminating files and dismantled the crematoriums, but left intact the camp buildings. With its evacuation, 33,000 prisoners were ordered on a death march. Many died or were killed. When the camp was liberated, 3,000 inmates were found alive.

The Soviet Union, the occupying power in eastern Germany, converted Sachsenhausen into a camp for political prisoners before closing in 1950. East Germany, which ruled the eastern half of the country before the unification of Germany in 1990, established a memorial and a museum on the site in 1961.

Today, the complex consists of 11 permanent exhibitions covering all aspects of life in the camp.

Barracks 36, a musty, reconstructed building where Jews were housed, tells their story through photographs, documents and letters. Neo-Nazis damaged it in 1992, but it was rebuilt.

The commandant’s house was converted into a museum several years ago.

When I finished my tour of the camp, I breathed a sigh of relief, knowing I had been to hell and back.