The Toronto International Film Festival and Human Rights Watch are co-presenting the Human Rights Watch Film Festival at the TIFF Bell Lightbox from April 18-25. One of the films, On My Way Out: The Secret Life of Nani and Popi, is about a Holocaust survivor who finally comes clean about himself. It will be screened on April 18 at 8 p.m. Another film, Muhi — Generally Temporary, which will be screened on April 19 at 6:30 p.m., deals with the impact of the Arab-Israeli conflict on a Palestinian family from the Gaza Strip.

Muhi, by Rina Castelnuovo-Hollander and Tamir Elterman, tugs at the heart.

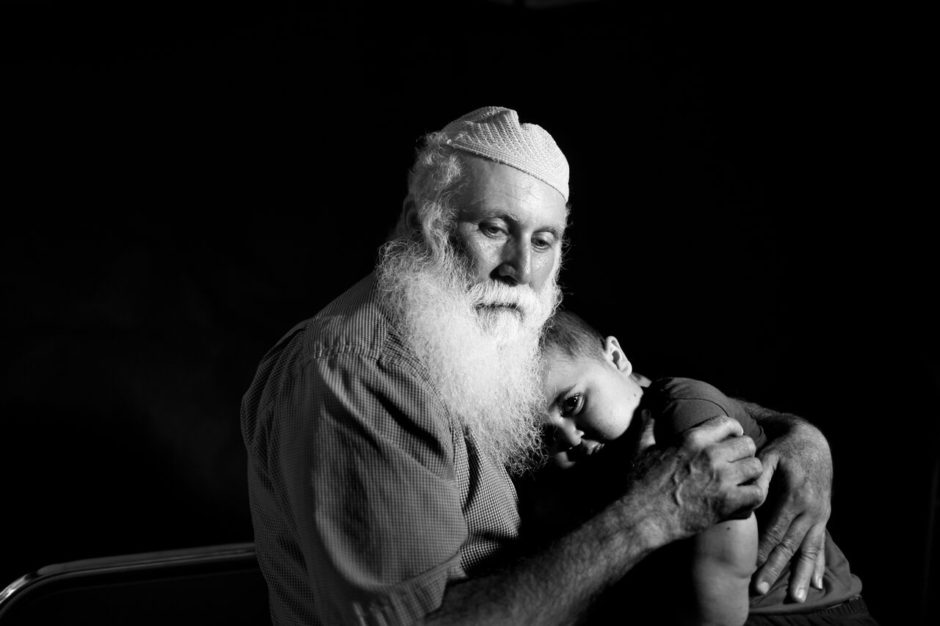

A Palestinian Muslim boy of about seven years old, Muhi has lived much of his life in a ward at the Tel Hashomer Hospital in Tel Aviv. His constant companion and surrogate father, Abu Naim El Farrah, is his doting grandfather.

The hospital, a clean and well-lit modern facility, is Muhi’s sanctuary and prison. Muhi arrived at Tel Hashomer in dire condition. A catastrophic immune disorder left him fighting for his life, and his only chance for survival was in Israel, which has been at war with the Hamas regime in Gaza for the past 11 years.

Regrettably, Israeli doctors could only save Muhi by amputating all his limbs. His arms and legs have been fitted with prosthetic extensions, but Muhi needs the most sophisticated care to survive. No hospital in Gaza, devastated by three wars with Israel since 2008, can provide him with such care. “This boy will have no life in Gaza,” says the Israeli physician who tends to Muhi. But due to Israel’s security regulations, Muhi’s movements are circumscribed. He and Abu Naim, a kindly looking man with a flowing white beard, can rarely leave Tel Hashomer. Such are the restrictions imposed on ordinary Palestinians — and Israelis — due to the animosity between Hamas and Israel.

This sensitive and touching film focuses mostly on Muhi, a cute and cuddly lad who lives in what is essentially a bubble. Having grown up in a Jewish milieu, he speaks fluent Hebrew, celebrates Jewish holidays and is only dimly aware of his Palestinian roots, Abu Naim’s efforts notwithstanding.

Despite his severe handicap, Muhi is bubbly and as mobile as someone in his constricted situation can be. But he has a burning question for Abu Naim: “Why did they amputate?” Abu Naim tries to explain, but it’s a difficult issue to unravel.

Buma, an Israeli humanitarian worker whose son was killed in combat in Lebanon, is a key figure in the movie. He played an important role in arranging medical care for Muhi in Israel, and now he is at Abu Naim’s beck and call.

Much of the film revolves around Muhi’s interactions with Abu Naim and his family from Gaza. His grandmother is an occasional visitor, as is his mother, Hiba, both of whom dress in conservative Muslim fashion. As Abu Naim and Hiba drive back to Israel from the border crossing, explosives fill the air. A new round of fighting has broken out.

As if Abu Naim does not have enough on his plate, he learns that his son has fallen into a coma. He rushes back to Gaza, but it is too late.

Muhi’s father, Ashraf, appears very briefly, never to be seen again.

Thanks to Buma, Abu Naim receives an Israeli work permit. But there is no certainty that Muhi will be allowed to stay in Israel indefinitely. It’s a tragic situation, but so is the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Brandon and Skyler Gross’ documentary, On My Way Out, is an unsettling profile of Roman and Ruth Blank, a Polish-Jewish couple who’ve been married for 65 years. They’ve known each other even longer, having met before the outbreak of World War II, which upended their lives. Now they live in Los Angeles.

“They’re two peas in a pod,” says one of their daughters, clearly proud of their loving relationship.

“This is the love of my love,” chimes in Ruth. “We’ve lived a happy existence. Life is beautiful because we have each other.”

In fact, their marriage is far more complicated than she lets on.

Roman finally comes out of the closet and admit he’s gay. Having been born in a country that greatly frowned upon homosexuality, he had no alternative but to hide his sexual preference. “I was born like that,” he says. “That was the way of the world.”

Ruth remains silent, but his daughters are shocked. “Oh, my god, it’s all a lie,” one says about his heretofore secret. “He’s really two different people,” his second daughter exclaims. Despite their reactions, they’re supportive of their father.

In the wake of their daughters’ comments, recriminations erupt between Roman and Ruth. “She wanted to go to her grave without discussing this,” says Roman. “He loved me as a brother, not as a husband,” Ruth counters. Nonetheless, Ruth is extremely attached to Roman. “I love this man. He’s my life.”

As it happens, Roman lived two lives. On the surface, he was a happily married man. Beneath the veneer, he had a male lover whom he regularly met. Ruth wanted to commit suicide when she discovered his secret, but she carried on in pain. “She kept it together,” Roman says in admiration. “She kept the family intact.”

The highlight of the film is when Roman attends a dance at the LGBT center and is crowned queen. “I wish I had been born 50 or 60 years later,” he says. “I would be completely free, like a bird, to find someone to fall in love with.”

Roman realizes, bitterly, that he cannot change reality. But at least he knows that Ruth has been an excellent partner.