We live in a fraught era when Jewish-Muslim tensions are flaring, not only in the Middle East but in European countries such as France. Has this always been the case? Historically, how tolerant of Jews have Muslims been since the birth of Islam in the Arabian peninsula?

Bernard Lewis, the distinguished scholar of Middle Eastern history who recently celebrated his 100th birthday, weighs in on this contentious issue in the paperback edition of The Jews of Islam (Princeton University Press), a work of impressive scholarship originally published in 1984.

In the 19th century, the Hungarian Jewish scholar Ignaz Goldziher, an admirer of Islam, propagated the theory that Jews enjoyed far more freedom and equality in Muslim societies than in Christian ones. Mark R. Cohen, a Princeton University professor emeritus of Jewish Civilization in the Near East, addresses this point in a foreword in The Jews of Islam.

Frustrated with the slow pace of emancipation in Europe and alarmed by the rise of a new brand of racist antisemitism, Europeans like Goldziher looked back nostalgically to medieval Islam, particularly in Muslim Spain, and concluded that Jews had fared considerably better under Islamic rule.

There were times when Jews and Muslims lived side by side in “a golden age of harmony,” as Lewis acknowledges. But to suggest that Muslim rule offered Jews an interfaith and interracial utopia would be an exaggeration. “Traditional Islamic societies neither accorded such equality, nor pretended that they were so doing,” writes Lewis, pointing out that both the Quran and the hadith invariably presented Jews in a negative light.

Under Islam, Jews — and Christians and Zoroastrians as well — were regarded as dhimmis, or protected people, whose rights were limited. As Lewis reminds us, full equality could only be attained by free male Muslims, even though a few dhimmis reached exalted positions.

As he notes, non-Muslims lived lives of uncertainty, were required to pay a special jizya tax and were bound by a maze of restrictions with respect to the clothes they could wear, the beasts they could ride, the height of the synagogues or churches they could build, and so on.

Dhimmis normally enjoyed communal autonomy in family, personal and religious matters, but in their relationships with Muslims, they were treated unequally.

“There was only one way in which Jews could always overcome (their) difficulties, and that was by conversion to Islam,” he says. “Considerable numbers of Jews, for one reason or another, embraced Islam.”

Some of these converts became antisemites and producers of anti-Jewish polemics, he says.

So long as dhimmis were willing to abide by the stringent rules that reduced them to second-class status, they were free to practice their respective religions and pursue their livelihoods. But once they were no longer prepared to accept or respect these restrictions, they were subjected to a tightening of the rules.

Trouble also arose when dhimmis were seen to be acquiring too much wealth or power. In such instances, violence could break out. As an example, he cites the massacre of Jews in Granada in 1066.

On a broader basis, the relationship between dhimmis and Muslims was affected by the state of relations between Islam and the outside world. When Islam was on the defensive, from the Crusades onward, the position of dhimmis deteriorated.

“On the whole, in contrast to Christian antisemitism, the Muslim attitude toward non-Muslims (was) one not of hate or fear or envy but simply of contempt,” he adds.

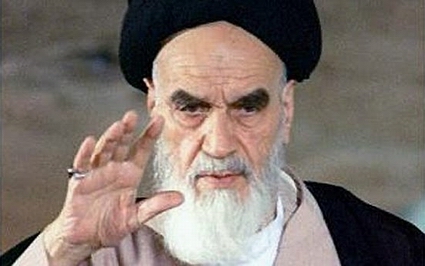

Unlike Sunni Muslims, Shiite Muslims, particularly in Persia, were concerned with the question of ritual purity. Such antiquated beliefs virtually vanished in the early 20th century, only to be resurrected by the first spiritual leader of revolutionary Iran, Ayatollah Khomenei.

Despite the burdens they were forced to bear, dhimmis were better off than non-Christians in Christian Europe, he says. “But their status was one of legal and social inferiority.”

Jews in the Ottoman Empire, though subject to the regulations of dhimmitude, were favored for their economic skills and international connections. But after the reforms of 1856, Jews and other non-Muslims were granted equal citizenship. The enclosed Jewish quarter, or mellah, was uncommon in Ottoman lands, but common in Morocco.

According to Lewis, the Jews of Persia during the Safavid dynasty were not only perceived as infidels but as ritually unclean. “Unlike the sultans of Turkey and even of Morocco, the shahs of Iran of the Safavid and the succeeding dynasties were usually unwilling to allow any place to Jews at their courts or in any positions of power and influence.”

During the 19th century, Persian Jews were rarely protected from the wrath of a generally hostile Muslim population. A Jewish traveller, J.J. Benjamin, travelled through Persia during this period and found, for example, that Jews were “subjected to the greatest insults” and forbidden to inspect goods in a store.

Conditions for Jews improved in the wake of the 1905 constitutional revolution and the fall of the Qajar dynasty in 1925, says Lewis.

In his judgment, the intervention of Western powers in the affairs of Jews in Islamic lands did not always work to their advantage: “While Jewish pressures and liberal principles sometimes combined to produce government action in favor of the Jews, there were other forces, hostile to Jewish emancipation and 19th century enlightenment, which worked in the opposite direction.”

European-style antisemitism first appeared among Christian Arabs in the 19th century and among Muslim Arabs in the 20th century. The first antisemitic tracts in Arabic were translated from the literature of the Alfred Dreyfus affair, while the first edition of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion was published in 1927 in Cairo.

“There are now more translations and editions of the Protocols in Arabic than in any other language,” Lewis claims.

The Arab-Israeli dispute has exacerbated antisemitism in the Arab world. From 1941 to 1948, numerous outbreaks of anti-Jewish violence in Iraq, Syria, Egypt, Yemen and Morocco broke out during which hundreds of Jews were killed in pogroms.

“All these events predated the establishment of the state of Israel and no doubt contributed to some extent to its creation,” he observes. “That, in turn, weakened the position of Jews in Arab countries, already weakened through their perceived association with the West.”

Mass numbers of Jews in the Arab world emigrated following the emergence of Israel as a sovereign state. Few remain today, prompting Lewis to conclude: “The Judaeo-Islamic symbiosis was another great period of Jewish life and creativity, a long, rich and vital chapter in Jewish history. It has now come to an end.”