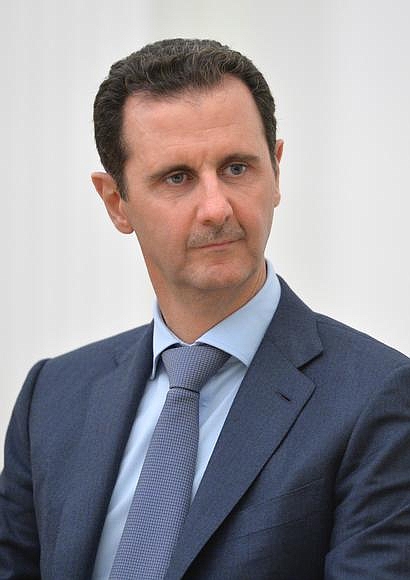

The burning question following the United States’ cruise missile strike against the Al Shayrat air force base in Syria on April 6 is whether the Trump administration has fundamentally changed its policy toward the Syrian regime of President Bashar al-Assad.

Less than a week before two U.S. destroyers in the eastern Mediterranean Sea fired 59 Tomahawk missiles at Syria in response to its reported chemical weapons attack on the town of Khan Sheikhun, killing more than 80 Syrian civilians, the United States appeared to have abandoned its objective of trying to force Assad from power.

That policy was formulated by Trump’s predecessor, Barack Obama, who repeatedly called on Assad to step aside for the good of his country, a message he consistently ignored. In opposing the Assad regime, Obama applied constant pressure on him, supplying moderate rebel groups with small arms and providing funds for training their fighters. Although Obama refused to send American troops to Syria to fight alongside the rebels, he dispatched several hundred special forces operatives to train their recruits.

Eventually, Obama focused his efforts in Syria on battling Islamic State, the jihadist organization that has taken a leading role in confronting the Syrian government, which is backed by a coalition consisting of Russia, Iran, Hezbollah and a host of Shiite militias from Iraq and Afghanistan.

The United States commenced air operations against Islamic State and other extremist outfits in Syria in September 2014, months after the U.S. air force began targeting Islamic State bases in Iraq. Unwilling to become embroiled in Syria’s civil war as a combatant, the Obama administration refrained from bombing Syrian military sites. But since 2016, U.S. advisers have been helping Syrian fighters, mainly Kurds, in their attempt to retake the northern city of Raqqa. Captured by Islamic State in 2014, Raqqa is the de facto capital of its self-styled caliphate.

Before his election as president, Trump maintained that the United States should not allow itself to be dragged into Syria’s civil war, which erupted in 2011 and has since claimed the lives of more than 400,000 Syrians and turned Syria into a charnel house.

During the U.S. presidential campaign, Trump — the Republican candidate — said he did not care for Assad, but implicitly praised him for waging mortal combat against Islamic State. Setting out his chief priority in Syria, Trump promised to destroy Islamic State, possibly in cooperation with Russia.

In line with this pledge, Trump increased the number of U.S. boots on the ground in Syria to almost 1,000, while the top American commander in the Middle East, General Joseph Votel, disclosed that the U.S. military presence in Syria would be upgraded in accordance with Washington’s aim of ousting Islamic State from its stronghold in Raqqa.

On March 30, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, Nikki Haley, signalled a further shift. “Our priority is no longer to … focus on getting Assad out,” she explained. “We can’t necessarily focus on Assad the way that the previous (Obama) administration did.”

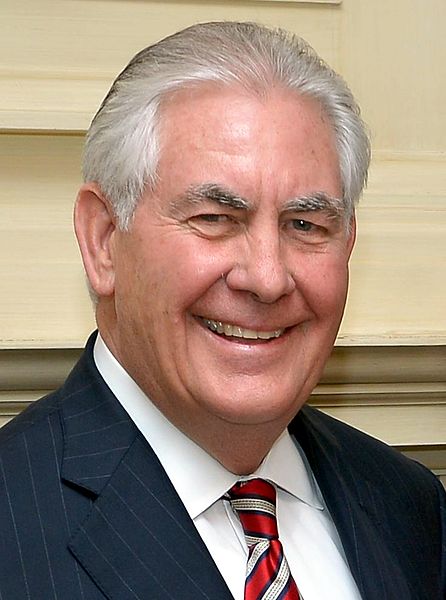

On the same day, during a visit to Turkey, U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson was asked whether Assad would have to vacate his office. He replied, “I think the status and the longer-term status of Assad will be decided by the Syrian people.”

A day later, Sean Spicer, the White House press secretary, indicated that the United States had broken with Obama’s policy regarding Assad. “With respect to Assad, there is a political reality that we have to accept,” he said. “The United States has profound priorities in Syria and Iraq, and we’ve made it clear that counter-terrorism, particularly the defeat of (Islamic State), is foremost among those priorities.”

These words must have been balm for Assad, who had expressed a willingness to work cooperatively with the United States in vanquishing Islamic State.

For Republican dissenters like Senator John McCain, the chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, the Trump administration’s tilt toward Assad was nothing less than short-sighted. Proceeding from the assumption that Syria would continue to be a magnet for Islamic radicals as long as Assad was in charge of its destiny, McCain said that a revaluation and revision of U.S. policy was now necessary. Unless Assad was removed, he warned, “more war, more terror, more refugees and more instability” could be expected.

It’s questionable whether the Trump administration would have heeded McCain’s recommendation had Assad not crossed a red line on April 4, when his air force bombed Khan Sheikhun, a rebel redoubt in Idlib province. Syria heatedly denies its involvement in that gory incident, claiming it’s part and parcel of “a false propaganda campaign” to blacken its image, but its denial rings hollow. Russia, Syria’s main ally, stands firmly behind Syria’s lie.

Assad, in fact, is a serial user of chemical weapons. In the summer of 2013, the Syrian army deployed chemical agents in the Damascus suburb of East Ghouta to repel a rebel offensive. Obama, having threatened to bomb Syria if Assad used poison gas, backed down. As a result of Russian pressure, Syria agreed to dispose of its vast stockpile of chemical weapons, satisfying the United States and its allies, including Israel.

But since then, Syria has reportedly used chlorine gas against its enemies on multiple occasions.

In the wake of Syria’s latest chemical attack, the United States vigorously condemned Syria. Chiding the Obama administration, Spicer said, “These heinous actions by the (Syrian) regime are a consequence of the past administration’s weakness and irresolution. President Obama said in 2013 that he would establish a ‘red line’ against the use of chemical weapons and then did nothing.”

Signalling that Washington would not stand idly by, Haley and Tillerson both suggested that Assad’s days as Syria’s leader were numbered.

“We don’t think that the (Syrian) people want Assad any more,” she said.

Tillerson said that Assad no longer had a role to play in governing Syria. He urged Russian President Vladimir Putin to consider dropping his support of Assad’s regime. This is wishful thinking. Since 2015, Russia has beefed up its military garrison in Syria considerably.

It was left to Trump himself to elucidate the new American approach to Assad. “My attitude towards Syria and Assad has changed very much,” he said on the eve of the April 6 bombardment, adding that Syria had “crossed a lot of lines” in deploying sarin gas against Syrian civilians.

Shortly afterward, the United States attacked Syria. It was not the first time U.S. forces had fired on the Syrian army. In December 1983, U.S. planes hit Syrian anti-aircraft batteries near the Lebanese capital, Beirut. Two months later, U.S. naval vessels shelled Syrian artillery positions in Lebanon, then enmeshed in a 15-year civil war that ended only in 1990.

The April 6 cruise missile barrage, aimed at Syrian MIG jets, aircraft shelters, air defence systems, radars, fuel storage sites and ammunition bunkers, was unprecedented. It marked the first time the United States had launched a direct attack on the Syrian government.

But was it game changer or merely an isolated one-off attack?

It ultimately depends on Syria.

If Assad is so rash as to deploy banned chemical agents once again, the Trump administration will likely react militarily, even in the face of fierce Russian opposition. Haley said as much yesterday when she warned, “We are prepared to do more, but we hope it will not be necessary.”

Whether this resolution to hold Assad to account translates into an unbending American determination to consider Assad a liability who should be pressured to resign is quite another matter. Putin, in any event, would vehemently oppose a change of regime in Damascus.

In the meantime, U.S.-Russian relations have plummeted since Tillerson’s barbed accusation that Moscow was lax in enforcing the 2013 agreement it brokered to eliminate Syria’s arsenal of chemical weapons. “Clearly, Russia has failed in its responsibility to deliver on that commitment,” he said shortly after U.S. missiles slammed into the Syrian airfield, destroying a small number of MIG jets and killing six Syrians. “So either Russia has been complicit or Russia has been simply incompetent in its inability to deliver on its end of that agreement.”

Certainly, these are fighting words for a U.S. secretary of state who supposedly desires to improve Washington’s strained relationship with Russia.