The United States has altered its view of the Palestinian refugee problem, which goes to the core of Israel’s protracted, often bloody conflict with the Palestinians.

The shift marks a significant break with U.S. policy and may yet affect ordinary Palestinians and the willingness of the Palestinian Authority to engage in peace talks with Israel.

In the past few days, Washington has set down two markers.

The Trump administration, which has adopted a strong pro-Israel position, has categorically rejected the “right of return,” the oft-repeated claim that Palestinian refugees are morally and legally entitled to go back to their former homes in what is now Israel.

And citing “failed practices” and rejecting the criteria by which the status of Palestinian refugees are defined, Trump has ended funding of almost $300 million to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) — the agency that channels assistance to five million refugees and their descendants in the Arab world — and has indicated he will seek better ways to assist Palestinians.

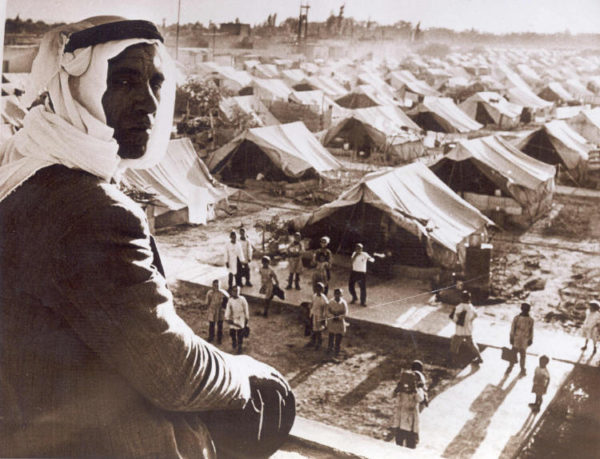

UNRWA was established in 1949 to resettle about 700,000 Palestinians displaced during the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948. Some fled voluntarily, confident they would return to their homes and properties following an Arab victory and Israel’s destruction. Still others were driven out by the Israeli army. In a few instances, such as in the city of Haifa, the Jewish leadership urged Arabs to stay put.

Approximately 160,000 Arabs remained in Israel following the war, though thousands were internally displaced and unable to return to their original towns and villages. The 1.8 million Arabs in Israel today, constituting 20 percent of its population, are their direct descendants.

Much to their anguish and anger, the Palestinians who wished to return were not permitted to do so by the Israeli government, which proceeded to demolish the 400 or so villages where they had lived. In places like Jaffa, where Arabs had been in the majority before 1948, buildings they had abandoned were taken over by new Jewish immigrants, such as my wife’s family, which arrived in Israel from Bulgaria in 1951.

For about the first 20 years of Israel’s existence, the United States supported the “right of return.” Both the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations pressed three Israeli prime ministers — David Ben-Gurion, Levi Eshkol and Golda Meir — to admit a relatively small proportion of the refugees, many of whom longed to return. Kennedy’s successors, from Lyndon B. Johnson onward, did not press Israel on this extremely sensitive issue.

Palestinians who had fled to Arab countries like Lebanon, Syria, Egypt and Iraq were welcomed, but there they faced a web of restrictions pertaining to residence, employment and social assistance. Only one Arab country treated the refugees decently — Jordan.

While Western nations poured immense resources into helping the Palestinians rebuild their lives, the Arab world exploited UNRWA to perpetuate the refugee imbroglio rather than solve it, Israeli scholar Adi Schwartz says.

“For the Arab world and the Palestinians themselves, resettling the refugees would have meant making peace with Israel, and that they were not willing to do,” he writes. “To the Arabs, the State of Israel was a grave disruption of the natural order, and the only remedy could be the repatriation of Palestinian refugees — thus turning Israel into an Arab state.”

Until quite recently, the Palestinians, fully backed by Arab regimes and the Muslim bloc at the United Nations, demanded the “right of return” and, implicitly, Israel’s conversion into a binational secular state, a goal pursued by the PLO until the 1993 Oslo peace process.

Israel had no intention of letting itself be destroyed by the weight of demography.

For the past 25 years, mainstream Palestinian opinion has been supportive of a two-state solution. But with the collapse of peace talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority four years ago, this option is considerably less popular today among Palestinians and Israelis.

Hamas, which controls the Gaza Strip, continues to champion the “right of return,” but the Palestinian Authority, which administers a small part of the West Bank, appears to have dropped this demand. On August 29, PA President Mahmoud Abbas met several Israeli peace activists at his headquarters in Ramallah and informed them he does not endorse the “right of return.”

“He told us he does not support or want a solution to the issue of refugees that would ‘destroy Israel,'” said Ilai Alon, a professor at the Interdisciplinary Center in Herzliya and a fluent Arabic speaker.

Alon’s son, Kfir, said that Abbas had agreed it would be “unreasonable” for Israel to “absorb all” Palestinian refugees. “He told us he opposes that because it would destroy Israel. But he also said that we need to find a solution to the issue of the refugees.”

On the same day as this news appeared in the Israel media, Nikki Haley, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, declared that the “right of return” should be removed from “the table” as an issue.

On August 31, the United States — which has provided one-quarter of UNRWA’s funds — announced that financial help to that organization would hereby cease. President Donald Trump’s senior advisor and son-in-law, Jared Kushner, reportedly pushed Trump into blacklisting UNRWA, his decision supposedly based on the assumption that a cutoff of funds would induce the Palestinian Authority to officially drop its insistence on the “right of return.”

Trump’s move was not unexpected.

Last January, after sharp Palestinian criticism of his move to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and move the U.S. embassy there, the United States withheld $65 million in assistance to UNRWA. Several days ago, the United States said it would slash a further $200 million in aid to the Palestinians, but release millions of dollars for programs to enhance Israel’s security cooperation program with the Palestinian Authority.

These cuts will have a serious impact, since Palestinian Authority budget for 2018 is in deficit to the tune of $1.8 billion and Arab states like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates already have reduced monetary aid to Palestinians. In addition, Israel has withheld tax funds in protest over its policy of supporting Palestinians whose breadwinners have been imprisoned in Israeli jails.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has praised the new American policy.“Consolidating the refugee status of Palestinians is one of the problems that perpetuates the conflict,” he said on September 1.

But cuts to UNRWA’s budget could have grave repercussions.

The Palestinian Authority could well reject the Trump administration’s peace plan, which is shortly to be unveiled, and boycott future talks with Israel.

Basic services in Palestinian refugee camps will probably have to be curtailed, and their absence could undercut the quality of Palestinians’ lives, weaken the Palestinian Authority, strengthen Hamas and other radical elements among Palestinians, and thereby undermine Israel’s security.

But at the end of the day, Palestinian refugees should wean themselves off UNRWA largesse, and Arab countries should try to integrate them into their respective societies. In the interests of defusing the Arab-Israeli dispute, Western powers should compensate them for their material losses, and Israel should absorb a symbolic number of refugees.

In short, the Palestinian refugee problem should not be allowed to fester indefinitely.