The village of Le Chambon-sur-Lievre is extremely remote. High in the mountains of southern France, it’s protected by a shield of escarpments and rivers. During the winter months from October to April, heavy snow drifts cut it off from the world for weeks at a time.

Thanks in part to its location, Le Chambon was able to play a valiant role as a safe haven for some 5,000 imperilled individuals during World War II. Jews, communists, anti-fascist resisters and Freemasons were hidden there by sympathetic villagers during the German occupation from the spring of 1940 to the summer of 1944.

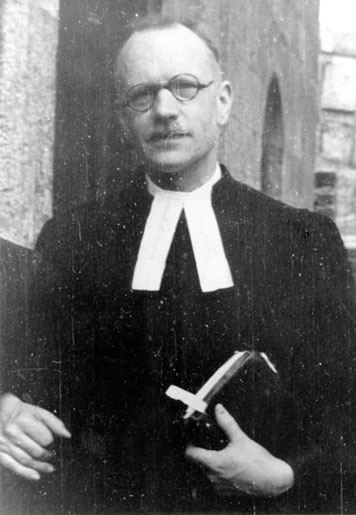

Its remoteness, however, does not provide a full explanation of why Le Chambon, a stronghold of Huguenots, came to their rescue. Part of the answer lies with a half-French, half-German Protestant pastor, Andre Trocme, who risked his life to save these strangers.

In what Caroline Moorehead describes as a “conspiracy of good” in Village of Secrets: Defying the Nazis in Vichy France (Random House), Trocme and a band of like-minded Good Samaritans took it upon themselves to hide and feed the hunted and smuggle still others to safety in neutral Switzerland.

At a moment in history when civilized norms were all too often cast aside, Le Chambon broke ranks with the forces of evil, expediency and indifference and took a stand. In this lucid account of courage and grit, Moorehead profiles not only a village of distinction, but a fascist regime that sold out the hallowed democratic principles of a great nation.

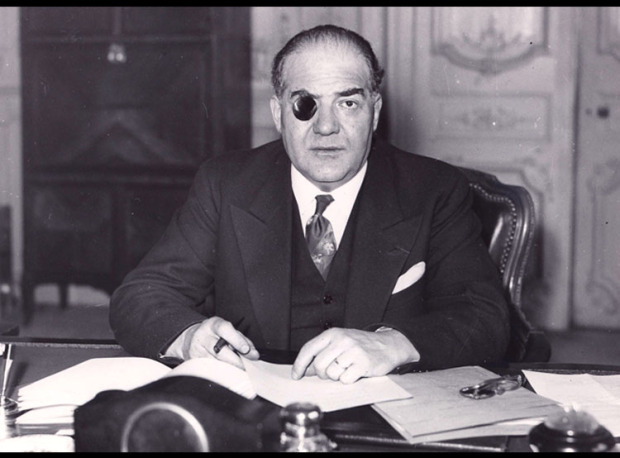

Vichy France, under the leadership of World War I hero Henri Petain, singled out Jews for persecution. Within months of France’s defeat in 1940, Vichy marginalized and demonized Jews through the first Statut des Juifs. The director of the Commissariat General des Questions Juives, Xavier Vallat, was a devout Catholic, a lawyer and an antisemite. Considered too soft, he was soon replaced by Darquier de Pellepoix, who was only too glad to do the bidding of the Germans.

On July 16, 1942, Vichy commandeered 9,000 French policemen to round up 28,000 Jews in Paris. They caught 12,884 Jews and deposited them in the Velodrome d’Hiver, a cycling stadium, where conditions were appalling. On the fifth day, they were transferred to Drancy, a nearby internment camp. From there, they were shipped straight to Auschwitz in Poland.

As Vichy betrayed French democracy, Le Chambon upheld them, even after two unsettling developments. In the winter of 1942, 170 wounded German soldiers — 80 officers and 90 enlisted men — were brought to the village to convalesce, but their presence had no ill effects. Less than a year later, the Commissariat General des Questions Juives launched an investigation to confirm whether Le Chambon was an “escape network for Jews.” Moorehead explores this incident at length.

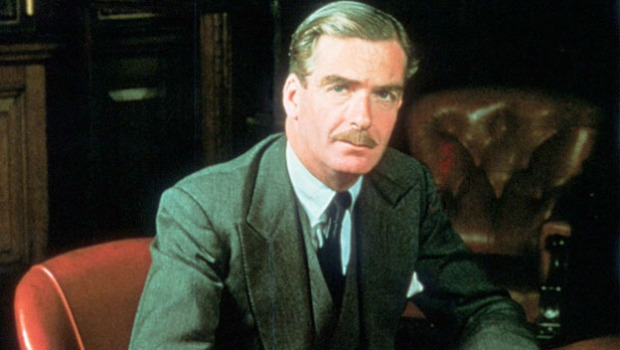

By that point, the Holocaust was no longer shrouded in secrecy, she points out. At the end of 1942, Carl Burckhardt, head of the International Committee of the Red Cross, received a report on Nazi Germany’s genocidal actions. He passed it on to the Allies, and on Dec. 17, 1942, they issued a denunciation of the “bestial policy of cold-blooded extermination directed mainly against the Jews.” The statement was read out in the British House of Commons by the foreign secretary, Anthony Eden, and in Washington, D.C. by the U.S. president, Franklin Roosevelt.

Meanwhile, the hidden Jews in Le Chambon, against all odds, remained unmolested. “What made their safety all the more extraordinary was that throughout the rest of France, the arrests and deportations of the Jews had not let up,” she observes.

By 1944, 75,000 Jews had been shipped to Nazi extermination camps in Poland.

Le Chambon’s rescue of Jews, which was recognized by Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust research and education center, did not become well known in France until the early 1970s. As Moorehead says, the altruistic residents of Le Chambon did not seek publicity for their good deeds.

***

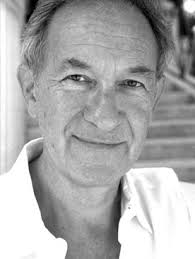

Simon Schama, a professor of art history and history at Columbia University in New York City, has written an illuminating book, The Story of the Jews, published by Allen Lane. Adopted from his acclaimed BBC/PBS series, this volume spans millennia and continents and places a flurry of events in historical context.

Calling it a tale of adversity and triumph and of wretchedness and splendour, Schama, a Briton, tells the story of a people whose culture and customs have been affected by a plethora of influences.

Schama is a scholar of vast erudition who’s not afraid to think outside the box. Consequently, The Story of the Jews is original in conception and sweeping in scope.

It’s one of those rare books that transcends the boundaries of time and is likely to be relevant in 10 years or in 50 years.

That’s a feat of scholarship.