Friedrich Kellner, a German civil servant, kept a secret diary from 1939 to 1945 in which he charted Germany’s inexorable descent into war, totalitarianism and genocide. A committed Social Democrat and a steadfast opponent of Nazism, he was born in Mainz and lived in the small Upper Hesse town of Laubach, 73 kilometres northeast of Frankfurt, from 1933 onwards.

Kellner moved to Laubach to escape retribution from Nazi activists in Mainz. Ironically, Laubach was a Nazi stronghold. Whether he was aware of this is unclear.

By the time Kellner wrote his first entry, only a few Jews were still left in Laubach, the remainder having fled. They certainly had good reason to leave. Antisemitism was deeply ingrained in the region, and the leader of the Nazi Party there, Jakob Sprenger, was an ideologically zealous antisemite who made sure that his district would be the only one in the country that deported intermarried Jews in a systematic manner.

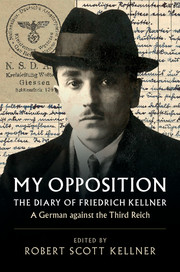

Kellner’s grandson, Robert Scott Kellner, discovered his diary in 1960 and worked tirelessly to publish it. My Opposition: The Diary of Friedrich Kellner, A German Against the Third Reich, published by Cambridge University Press, is a powerful account of a nation that lost its way after many of its citizens cast their lot with a fanatical movement that brought Germany to its knees and the very edge of the abyss.

The first lines in Kellner’s diary are prophetic. In a reference to the outbreak of World War II, he writes, “Hitler ordered the invasion of Poland. The German officers did not object. The German troops did not rebel. The German people did not protest. Now they and the entire world will pay for their indifference to tyranny and terrorism.”

Speculating why Germany succumbed to the allure of National Socialism, he wonders: “How was it possible a cultured people like the Germans could have handed absolute authority to a single man? One must despair over the total obtusiveness and cowardliness.”

Kellner’s indictment of Nazi antisemitism is unsparing. “If the Jews, who over the centuries contributed demonstrable achievements in the economy for the total development of a nation, can be made a people without rights, then this is an act unworthy of a cultured nation. The course of this evil deed will indelibly rest on the entire German people. The authors, the National Socialists, will have disappeared some day; their deeds, however, will live on.”

On August 31, 1940, he observes, “Tonight marks the third time English airplanes have flown over Berlin. The war has taken a turn so that the masters in Berlin finally can feel something of it firsthand.”

At the beginning of 1941, he says, “We are in a strange state of mind. I well remember reading in the newspapers just before the war began that we would not have a long war. No one speaks of this anymore. How does the ostrich do it — he sticks his head in the sand and so does not have to see anything. We are just like that.”

He recoils at the thought that Germany might win the war. “Just the idea of world domination by Germany is a danger,” he notes on April 19, 1941.

The Nazi regime greeted Rashid Ali al-Gaylani’s revolution in Iraq in 1941 with glee. Kellner punctures the joy: “National Socialist sympathies go less to the inhabitants of Iraq and much more to the abundance of (Iraq’s) oil.”

Following Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, he writes, “Are the Russians aware of the boundless stupidity they committed in 1939. For the Russian dictator to seal a treaty of friendship with an enemy that had worked day and night to stir up his allies to fight Russia was a dreadful, a really monstrous, ‘achievement.’ For that, this nation is punished.”

He adds this prescient sentence: “He who lays Russia in ruins today must reckon with its resurrection tomorrow.”

Toward the close of 1941, Kellner makes these astute observations:

“The German people must acknowledge there is no superior race/The German people have to learn they can never change their position by power politics/We can solve the problems of humanity only with decent attitudes, respect for the rights of others, and acknowledgement of justice/The army still fights for Hitler’s tyranny and the Nazi pigsty! When will enlightenment come?”

Almost midway through 1942, he offers this bon mot: “My wife and I were of the opinion from the beginning Germany would lose this war. We often were out on a limb all by ourselves.”

Peering into the future, Kellner predicts what lies ahead. On August 13, 1942, he writes, “There will be a cruel accounting, but this fate is earned. There are men among the German people who could bring about a change, but nobody moves. Therefore it is completely justified that the entire German people — without exception — be held to account. The punishment has to be implacable and effective.”

On September 16, 1942, writing of the fate of local Jews, he reports, “In the last few days, the Jews from this region have been removed. The families Strauss and Heynemann were taken from Laubach. I heard from a reliable source all the Jews were taken to Poland and murdered there by SS brigades. This cruelty is horrible. Such atrocities will never be able to be erased from the book of humanity. Our murderous regime has for all times besmirched the name ‘Germany.’ It is unfathomable for a decent German that no one can stop the activities of these Hitler bandits.”

Judging from a December 3, 1942 entry, there are no shortage of Germans who believe in the Nazi cause. As Kellner reports, a judge in Laubach told him, “The Jews work consciously toward the goal of creating wars so they can make blood money from the fighting.”

Kellner is utterly convinced that Hitler led German astray. On December 17, 1942, he vents his anger: “Adolf Hitler is the most cunning criminal of all times. His is Satan and the devil in one person. He is the bloodiest tyrant, filled up with cruelty and unremitting hardness.”

Under Nazism, real democracy no longer exists. As Kellner writes on September 20, 1943, “It is highly dangerous to speak the truth … When our enemies allow even the sharpest public criticism, they display strength. With us in Germany, thinking is a dangerous thing.” He adds in a subsequent entry, “Nationalism Socialism is a disease, a plague.”

He has harsh words for Sweden, a neutral country that traded with Germany during the war. On March 21, 1944, he hurls invective at the Swedes: “Sweden is responsible for the useless extension of this war. Perhaps a careful investigation would show Sweden carries the principal debts of both world wars. At the least, without Swedish ore supplies, Germany could not have carried out either war to such long duration. When I say Sweden, I mean the big income earners and capitalists of that country.”

Kellner’s contempt of Joseph Goebbels, the German propaganda minister, is palpable. As he fulminates on October 28, 1944, “Our enemies are not the ones destroying Germany. Goebbels and his comrades are doing it. If every house becomes a fortress — as Dr. Goebbels wishes — then every house will equally be destroyed. These men want the entire German people to go down with them.”

In an intriguing entry dated November 16, 1944 and headlined “Arabs in Germany uniforms,” he writes, “For some time now a unit in the army has been building up a troop that in the beginning was designated as the German Arab Legion. In this formation gathered the most active elements of Arabs living in Europe.” Kellner goes on to say that the instructors in this legion are mostly ethnic Germans who had lived in Templar colonies in Palestine and who “had learned the language and nature of the Arabs …”

Just months before the end of the war, Kellner lashes out at the Nazi regime. “The coming generations and the foreign countries will never understand why the German people did not stop the Party leaders by force and turn against the Party tyranny so this horrible war could be terminated.”

Continuing in this vein on April 21, 1945, he writes, “History will note for eternity the German people were not able on their own initiative to shake off the National Socialist yoke. The victory of the Americans, English and Russians was a necessary occurrence to destroy the National Socialists’ decisions and plans for world domination.”

On May 8, a day after Germany’s surrender, Kellner unleashes a final blast: “Adolf Hitler never would have been in a position to lead this accursed war were it not for an extremely large number of unscrupulous accomplices at his side. These involved not only the General Staff and high-ranking officers but also managers of major industries, scholars and diplomats.”

In the wake of the war, Kellner was appointed deputy mayor of Laubach. In this capacity, he played a major role in determining which local Nazi Party members should be disqualified from their professions and from public office. As a fierce adversary of the Nazis, he had earned this right in spades.