Acre, a historic port in northern Israel, sits on the remnants of the world’s only fully preserved Crusader city.

Visitors who spend a few hours in its old quarter, designated as a World Heritage site by the United Nations, can feast their eyes on subterranean Crusader ruins that were uncovered by archaeologists in the 1950s and 1960s.

Additional excavations in the 1990s brought to light a complex of halls, public toilets and sewage systems, among other facilities.

By any yardstick, the Crusader era is an intriguing one.

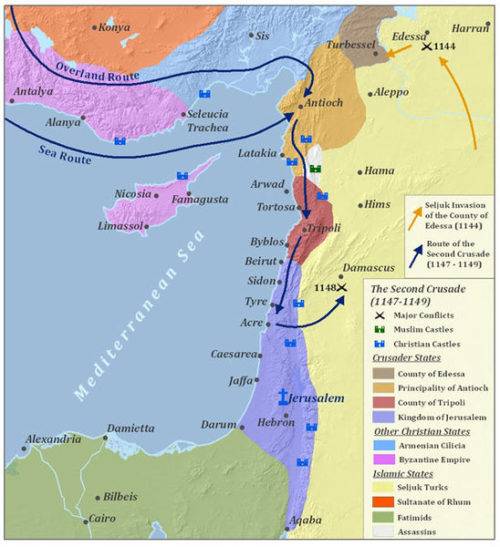

The Crusaders were European religious zealots who waged a series of wars to wrest Jerusalem and the Holy Land from Muslim rule. The first Crusade lasted from 1095 to 1099, and was followed by eight more Crusades, the last one ending in 1272.

Long before the Crusaders set foot in Palestine, Jews and Arabs lived in Acre, known as Akko in Hebrew. Once the Crusaders landed in 1104, Acre was dubbed Saint-Jean d’Acre.

Recaptured by Salah al Din, or Saladin, Acre was reconquered by the Crusaders in 1191, their forces led by Richard the Lion-Hearted and Philip Augustus, the respective kings of England and France. Acre, the capital of the Crusader kingdom in Palestine, was a vital centre of commerce.

In 1291, it was captured by the Mamluks, spelling the end of the Crusader presence in the Holy Land.

Conquered by the Ottoman Turks in 1517, Acre gradually fell into decay, and was not revived until about the 18th century. Napoleon Bonaparte, commanding a French imperial army of 13,000 soldiers, appeared in Acre in 1799, only to be repulsed by the Ottomans and Britain.

Under the 1947 United Nations Palestine partition plan, which was rejected by the Palestinians and their Arab allies, Acre was assigned to a proposed Arab state. During the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948, it was seized by Jewish forces.

Although three-quarters of its Arab inhabitants fled, Acre today has one of the highest proportions of Arabs in a mixed Israeli city. Of its 60,000 residents, 28 percent are Israeli Arabs. At its height as a mercantile hub during Crusader times, Acre’s population was 40,000. Most Arabs live in the old city, a mass of crumbling Ottoman-style buildings set amid a colorful maze of winding cobblestone streets and alleys and open markets redolent of the heady aroma of spices, falafel and urine.

The atmospheric walled old quarter is the focal point of Acre’s Crusader past. It’s administered by the Old Akko Development Company, which carries out excavations, tends to conservation efforts and conducts tours.

The tour I joined began at the Citadel, an Ottoman fortification built on the ruins of a building constructed in 1080 by the Order of the Hospitalers, a Christian monastic organization that looked after pilgrims, the poor and the sick. Later, as the Crusaders consolidated their grip on Acre, the order morphed into a political and military organization dedicated to defending the Crusader kingdom.

During the British Mandate period from 1922 to 1948, the Citadel was a prison. The Irgun, a Zionist-Revisionist militia, broke into it in 1947 to free Jewish fighters due to be hanged. Leon Uris, the American pulp novelist, incorporated that incident into his bestseller, Exodus. Hollywood film director Otto Preminger incorporated that jailbreak scene in his movie, Exodus, starring Paul Newman and Eva Marie Saint.

Directly beneath the Citadel is a big vaulted space, the Knights’ Hall, where European pilgrims slept, ate and stored their supplies. Eager to eradicate all signs of the Crusader footprint, the Mamluks covered the Knights’ Hall with sand, thereby inadvertently preserving it for posterity. As I gazed at a fluer de lis — a stylized lily or iris — carved into a corner of the thick sandstone wall, my guide said that only a small proportion of the Knights’ Hall has been excavated.

The public toilet, with 30 cubicles, is a sight to behold, as is the Turkish bazaar around the corner. Next, I saw an 18th century Ottoman bathhouse, consisting of hot rooms and a steam room with a marble fountain.

The most impressive structure in old Acre is the 18th century Mosque of Al Jazzar, which was built over a destroyed Crusader church, the Cathedral of the Holy Cross. Regarded as the most beautiful mosque in the Galilee, the green-domed house of prayer is distinguished by a soaring minaret, blue and brown murals and Persian carpets. A lock of hair, supposedly from the Prophet Mohammed’s head, is stored in a container and displayed once a year when the Ramadan fast ends.

Acre’s colorful outdoor market, a jumble of shops and stalls, is close by, as is the tiny Ramhal synagogue, which was established by a Jewish mystic in the 1700s, when Acre had a modest Jewish community.

The Templar tunnel, a low passageway 350 meters in length connecting the city centre to the harbor, was discovered by chance in the mid-1990s by a local resident who complained of foul odors from a blocked sewer.

The port of Acre, boasting a lovely marina, looks out at Crusader sea walls. Reinforced in the late 17th century, they survived Napoleon’s siege. Arab boys jump off the walls, asking tourists for money before plunging headlong into the aquamarine and cobalt waters of the Mediterranean Sea.