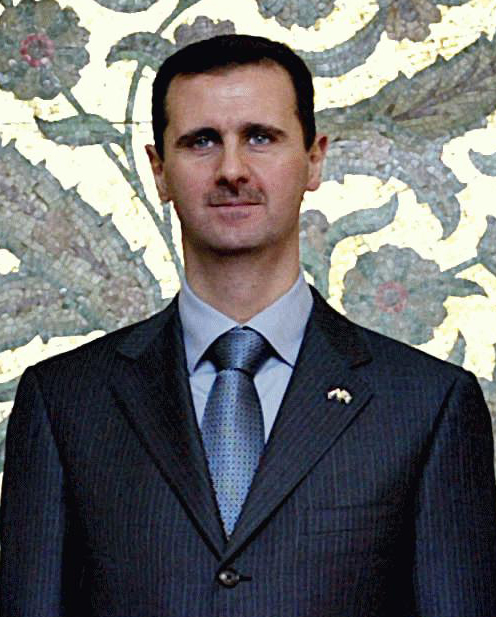

With eastern Aleppo back in his hands after four years of fierce fighting, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has won a significant victory in Syria’s five-year-old civil war.

As the last civilians and rebel fighters were evacuated from there on December 22, Assad could truthfully boast that every major city in Syria — Damascus, Aleppo, Homs, Hama and Latakia — was now under his firm control.

A few days before Syrian forces, backed by Russia, Iran, Hezbollah and Shiite militias from Iraq and Afghanistan, recaptured the eastern sector from the rebels, Assad hailed its imminent fall as a triumph of arms.

In a video, he grandiloquently compared it to the world wars of 1914 and 1939 and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

It was an overblown comparison, of course, but within the context of the Syrian civil war — the most destructive event in the Middle East since the 1975-1990 Lebanese civil war and the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War — it was a momentous moment, perhaps even a turning point in an extremely bloody war.

Thanks to his faithful allies, Assad is on a roll. In the 15 months since Russia’s bold intervention in the war, a gamble U.S. President Barack Obama claimed would end in grief, the Syrian regime has regained its footing.

There are still many battles ahead, since the rebels — a diverse group consisting of Syrian nationalists, Islamists and jihadists — still hold sway over the province of Idlib, near Aleppo, and the eastern city of Raqqa, the de facto capital of the jihadist Islamic State organization since 2014.

In other words, the rebels are still in charge of much of Syria, which remains a deeply divided, fractured and broken country probably in need of partition along ethnic and religious lines.

But for now, Assad can take solace from his success in retaking eastern Aleppo, which had been populated by about 250,000 civilians and several thousand rebels.

By any yardstick, Assad used ruthless and indiscriminate force to rout his opponents. Residential neighborhoods were bombed into rubble, leaving a cityscape resembling Berlin or Warsaw immediately after World War II.

The bombardments from the air and the ground were on such a massive and horrific scale that Syria and Russia stand accused of committing war crimes.

Their objective was to pound, terrorize and starve civilians into submission, a goal they achieved by means of brute force and an agreement brokered by Russia, Turkey and Iran to evacuate the eastern portion of the city. In exchange for their surrender, civilians and rebels were permitted to leave unharmed in convoys of buses headed toward rebel-held areas.

Assad has agreed to participate in future peace talks in Astana, the capital of Kazakhstan, under the auspices of Russia, Turkey and Iran. Russian President Vladimir Putin, Assad’s chief patron and protector, says a nation-wide ceasefire should be put into place before talks on a political settlement get under way.

Since the eruption of the civil war, a succession of high-profile international mediators have tried to defuse it diplomatically, but to no avail. The impasse is deep and daunting. Assad’s adversaries demand his removal. Assad adamantly insists on remaining in office. There seems little room for compromise.

Assad, who inherited the presidency in 2000 following his father’s untimely death, has been able to cling to power because the armed forces and the Russians have backed him to the hilt. In his playbook, survival is the name of the game, even if it means the piecemeal destruction of Syria and the death of hundreds of thousands of his fellow Syrians.

In retrospect, Assad has been the only authoritarian Arab leader to successively weather the Arab Spring rebellions, which broke out at the end of 2010.

Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, the president of Tunisia, fled to Saudi Arabia as an internal revolt gathered momentum. Hosni Mubarak of Egypt resigned after three weeks of turmoil, pushed out by his generals and the United States. Muammar Gaddafi, the Libyan dictator, fought back ferociously, but was defeated by a ragtag army of rebels and NATO airstrikes. Ali Abdullah Saleh, Yemen’s president, held on for a while, but was finally forced to abdicate.

Watching these developments unfold across the Arab world, Assad decided he would resist. He has beat back the rebels, and from an external point of view, his strategy of steadfastness has paid dividends, judging from the positions that two of his most bitter enemies, Turkey and Egypt, have adopted

At the risk of alienating one of his most important partners, Saudi Arabia, Egyptian President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi has backtracked. He now supports “national armies” in Syria, a euphemism for forces loyal to Assad.

The president of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, whose army has thrust into northern Syria to fight jihadists and Kurds and to establish a safe zone along the border, has reversed himself as well. Instead of clamoring for regime change in Damascus, he currently claims he is fighting “terrorism” in Syria.

U.S. President Barack Obama has consistently called on Assad to step down, but Obama has not targeted his regime per se. Indeed, the United States has confined itself to attacking Islamic State and other jihadist groups in Syria.

Donald Trump, the incoming U.S. president, says he wants to focus his attention on destroying Islamic State, while leaving Assad in power. This is a position that Putin has staked out too. If Trump and Putin can forge a viable working relationship, Assad will be the ultimate beneficiary.