What is it like being a Palestinian living outside the homeland?

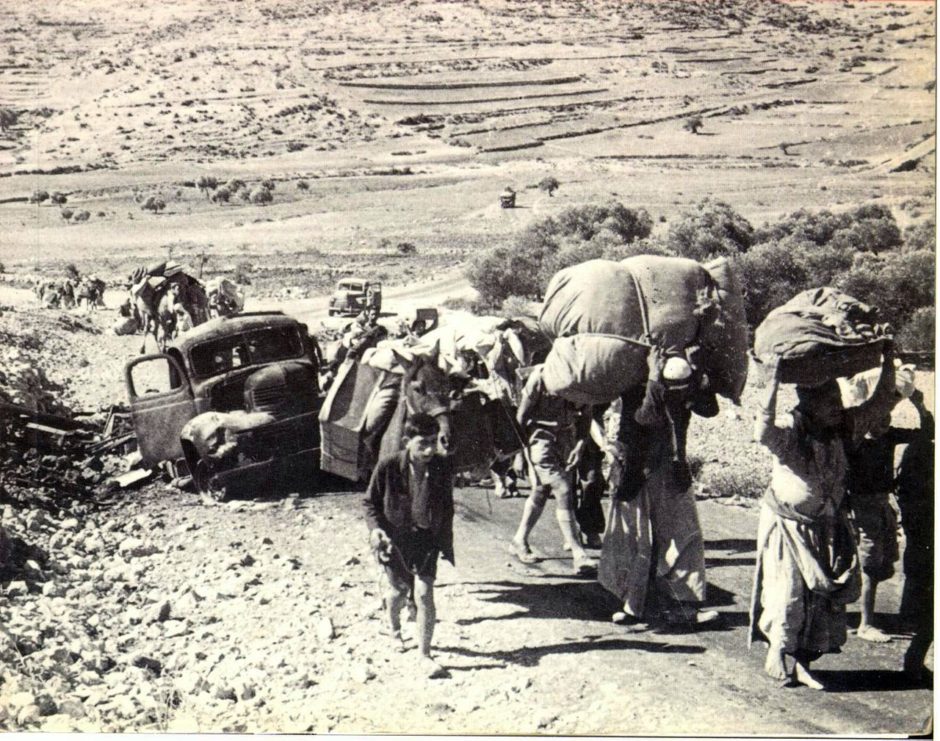

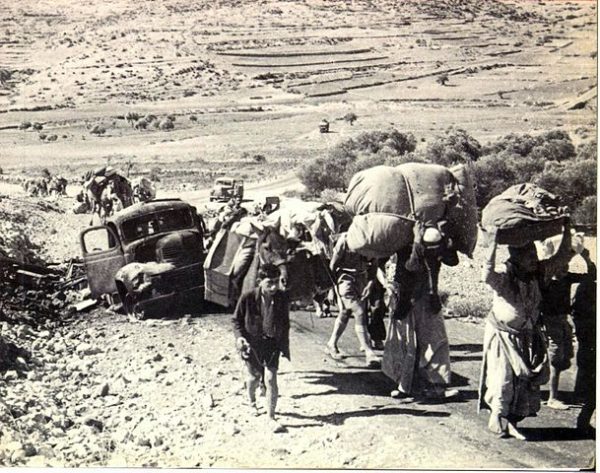

Seventy years after the eruption of the first Arab-Israeli war, which led to the dispossession of some 500,000 Palestinians from their homes in what is now Israel and to the intensification of the conflict between Zionism and Palestinian nationalism, this question remains very relevant.

Yasir Suleiman, a Palestinian scholar of modern Arabic studies at King’s College, Cambridge University, examines it through interviews with 102 Palestinian residents of North America and Britain, some of whom were born outside their ancestral land. His interviewees cross religious and gender lines.

Their recollections are found in Being Palestinian: Personal Reflections of Palestinian Identity in the Diaspora, published by Edinburgh University Press and distributed by Oxford University Press.

Samer Abdelnour, an academic born in Canada, writes, “My parents were working hard to make a life for us in Canada, yet Palestine was very much a part of their lives … I did not know Palestine but she was somehow there … Palestine was like the moon … something to talk and dream of, far away and out of reach; a place we never visited.”

Ishaq Abu-Arafeh, a pediatrician in Scotland, writes, “Being Palestinian means that I have to accept the most humiliating injustice in order to live as a second-class citizen in may own country under Israeli occupation. Palestinians are expected to live in refugee camps hoping for justice and a return to their homes and villages.”

Lama Abu-Odeh, a law professor at Georgetown University, says, “It is in ‘bad taste’ to be a Palestinian in the U.S. You risk hurting the feelings of your Jewish host, or embarrassing your non-Jewish co-hosts into taking a ‘position.’ To be a Palestinian in the U.S. is to be a party pooper…”

Salman Abu Sitta, an engineer born in Beersheba, is extremely bitter. “We knew the enemy in name as ‘the vagabonds of the world.’ Although the enemy spoke a babel of languages and wore a wide variety of semi-uniforms, it had a secret tongue, known as Hebrew, which nobody knew. We knew nothing about the invaders’ structure, strength or their plans other than that they attack, conquer, kill and expel people from their homes …” He adds, “To be Palestinian is not to forget, nor to surrender this great heritage, not to kneel and resign to the tragedy of the Nakba. To be a Palestinian is to resist the ravages of evil deeds, to insist on the restoration of rights and to plan for their restoration.”

Sami al-Arian, an American born in Kuwait and raised in Egypt, was a key member of Islamic Jihad when he was arrested. “For decades, Palestinians have been the victims of oppression, transgression, occupation, brutality, violence and abuse,” he writes, adding that he exists in “a permanent state of homelessness, statelessness and separation” from his siblings and extended family. “Being Palestinian is to be profoundly sensitive to the ugliness of racism and institutional discrimination, to the suffering of others, as well as any injustice inflicted on human beings individually or collectively.”

Sa’ed Atshan, a Harvard graduate and a post-doctoral fellow at Brown University, muses, “Every people live in their country, but for Palestinians, our country lives in us.”

Aida Bamia, a graduate of the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London and a professor emerita of Arabic language and literature, writes, “My victimization as a Palestinian has instilled in me an acute sense of justice and fairness.” Being optimistic and resilient, she still clings to the hope that she can return “to a Palestine I can call home, not a land under occupation ….”

Ramzy Baroud, a syndicated columnist and editor of PalestineChronicle.com, says, “I have lived in Seattle for many of the last twenty years, and in other parts of the world, but rarely have I not been aware of my identity as as a Palestinian.”

Dawoud el-Alami, a lawyer and teaching fellow at the University of Aberdeen, says, “Despite the fact that I was not born in Palestine, and have never lived there, throughout my childhood growing up in Egypt I knew I was a Palestinian in exile from my homeland.”

Najat El-Taji El-Khairy, a porcelain artist based in Montreal, writes, “Being Palestinian defines every fibre of my being. It weaves my daily life in all its complexities … It nourishes my veins with its exquisite culture, rich heritage and breathtaking landscapes. It calls for me wherever I go. I connect to my homeland with the scent of orange groves and the sight of olive and lemon trees.”

Amal Eqeiq, a native of the Israeli Arab town of Al Taybeh, teaches Arabic and comparative literature at universities in the United States. A Palestinian from Israel, holding an Israeli passport, she is is always racially profiled at Ben-Gurion Airport. “My blue passport, with a menorah engraved on its front page, does not protect me, as a Palestinian, from being strip-searched (and) getting tags in a different color on my luggage and body …”

Randa Farah, a profesor at the University of Western Ontario who was born in Haifa, recalls, “My childhood memories of the late 1950s and 1960s are of segregated schools for ‘dirty Arabs’ where it was forbidden to study our history, where our movement was restricted by law, where we were humiliated and excluded from Jewish-only spaces …”

Ghazi Hassoun, a physicist in the United States, says, “The 1948 Nakba, which led to my prospering family becoming refugees in Tyre, Lebanon, has been central to my life. Loss of home, community and country had a profound, shattering impact.”

Mohamad Issa, a retired professor of physics living in Scotland, has fond memories of his village, Muzera’h, which was razed to the ground: “Sweet tea flavored with maramia (sage) greeted me in the morning as we waited for my mother to return with hot bread from the communal stone ovens. After breakfast my brothers and sisters ran wild through the endless fields of red poppies, only returning to pick fresh fruit from fig and vine trees or gather eggs from chickens.”

Ghada Karmi, a physician from Jerusalem living in London, says she fits in nowhere: “There was no feeling of belonging and no secure future. The fear that stalked me was that I knight never know howe it felt to live in any own land and take my rightful place in it … Something shattered for us when our country was taken away …”

Jean Said Makdisi, a professor of English and humanities at Beirut University College who was born in Jerusalem, writes, “One thing is clear: To be a Palestinian … is to be the bearer of a continual, unbroken, violent history of political, social, military and cultural injustice, and to be perpetually obsessed with this historic set of grievances. Being Palestinian is not just a national experience, but a personal, deeply felt consciousness of loss and alienation.”

Aftim Saba, an American-based doctor born in Libya, observes, “Being Palestinian has been and continues to be very burdensome, intrusive and a perpetually indignant existence. The distractions from life’s hopes, aspirations and everyday joys are frequent.”

Simine Tepper, a programmer in Boulder, Colorado, writes, “Being Palestinian in the diaspora … is at once a wonderful feeling and sometimes an uneasy one. Wonderful because of the freedom from foreign occupation, from strip searches, curfews and checkpoints, but also because of the ability to live with dignity, hope and the freedom to plan and pursue one’s future. ”

These are heart-felt testimonies, denoting the fact that the Palestinian problem is central to the Arab-Israeli dispute and cannot be sloughed off.