The American constitution enshrines the principles of democracy and egalitarianism for all citizens. Yet for much of its history, the United States was not the land of freedom and opportunity for African-Americans. The injustices and humiliations they endured are presented with laser-like precision, intensity and emotion at the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee.

The museum recounts the inspirational story of the U.S. civil rights movement, in which American Jews played a disproportionately prominent role.

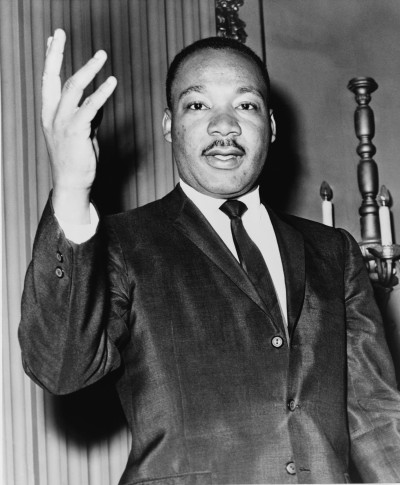

Appropriately enough, it’s housed in the old Lorraine Motel (450 Mulberry Street), where civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated by James Earl Ray on April 4, 1968.

After King’s murder, the segregated hotel, located in a black neighborhood, went into a steep decline and eventually closed. Concerned that the property might be bought and demolished by real estate developers, the Martin Luther King Memorial Foundation purchased it in 1982 with the intention of building a museum in his honor. Construction began in 1987, and four years later, the museum opened.

Although it focuses on the travails of African-Americans, the museum pays tribute to whites who left a legacy of compassion.

Cited as an example is Frances Slanger, a Jewish woman born in Lodz, Poland. During World War II, while serving with the 45th Field Hospital, she was killed in a German artillery barrage, becoming the only American nurse to die in the 1944 Normandy landings.

An adjacent exhibit is devoted to Helen Suzman, a Jewish parliamentarian from South Africa who railed against racial discrimination and segregation during the apartheid period.

Through its exhibits, the museum leaves no doubt that the battle for human rights in America was both violent and peaceful.

From the earliest slave revolts in the British colonies to the uprisings of the 18th and 19th centuries, African-Americans fought for their rights. The rebel Nat Turner, the subject of a novel by William Styron, turned to violence, but the abolitionist Frederick Douglas preferred non-violent means.

The legal struggle for equality hit a roadblock in the mid-19th century with the Dred Scott case, but the 1862 Emancipation Proclamation, enacted by President Abraham Lincoln, formally abolished slavery.

A series of constitutional amendments in the wake of the U.S. Civil War denied states the right to abridge the rights and privileges of American citizens and granted all Americans the right to vote, regardless of race and religion.

But after Reconstruction, an era during which federal troops occupied the southern states and African-Americans won many civic rights, a reactionary epoch of retrenchment set in. The Ku Klux Klan emerged and Jim Crow laws limiting the freedom of African-Americans went into effect, turning back the clock by decades. With the 1896 Plessy vs. Ferguson Supreme Court verdict, the 19th century ended with the races firmly separated and segregated.

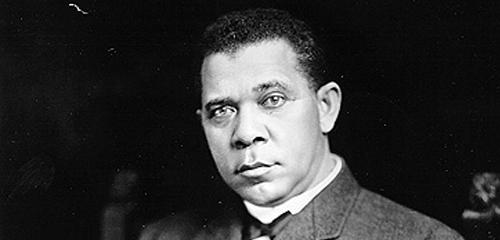

Some African-American leaders, like Booker T. Washington, stoically resigned themselves to the status quo, urging hard work and patience. But as a panel of stark photographs of race riots in New York, Atlanta and Houston suggests, other African-Americans staunchly rejected his accommodationist philosophy. Still others, like the firebrand Marcus Garvey, gave up on America altogether and founded the Back to Africa movement.

In a jolting reminder that open racism reigned supreme after the Civil War, the museum displays “colored section” signs that shamefully circumscribed the rights of African-Americans at public facilities from hotels to restaurants.

Documented, too, is the rise of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the National Urban League, both of which were in the forefront of combating racism, a phenomenon that affected Jews and other minorities as well. But as yet another exhibit points out, segregated units in the American armed forces were common before and during World War II.

The museum chronicles the major developments of the 1950s and 1960s — the Supreme Court ruling in the Brown vs. Topeka Board of Education case, the desegregation of Central High School in Little, Rock, Arkansas, the standoff pitting the University of Mississippi against the federal government in the James Meredith case, the voter registration drives, the sit-inns, the freedom rides and the bus boycotts.

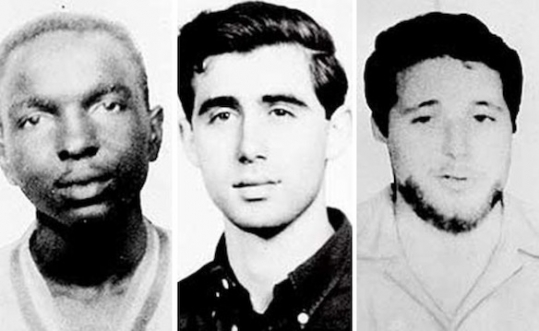

Reproductions of newspaper headlines recall those chaotic days, as do FBI “missing” posters of Jewish civil rights workers Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner and of their African-American co-worker, James Cheney, who were killed by the Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi.

Judging by Goodman’s and Schwerner’s martyrdom, American Jews were visibly involved in the struggle for the full emancipation of African-Americans. An inflammatory poster published by the racist/xenophobic National States Rights Party, based in Savannah, Georgia, attests to this fact. Accusing Jews of having encouraged “race mixing,” it singles out Arthur Spingarn, a Jewish founder and supporter of the NAACP, for opprobrium.

At the end of the tour, Martin Luther King’s room at the Lorraine Motel comes into view. Chilling the blood, it reminds a visitor that the campaign for human rights is a never-ending task.