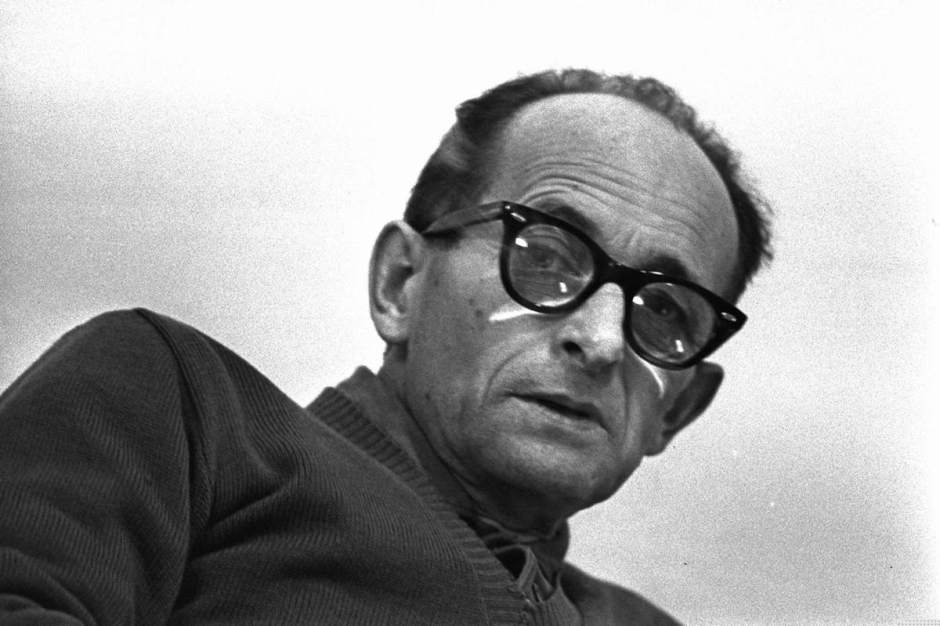

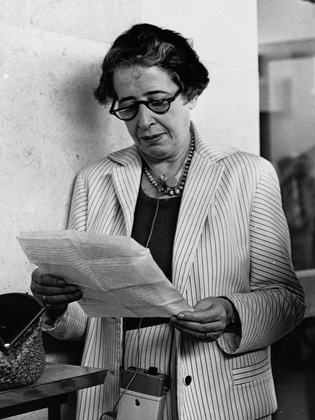

At his show trial in Jerusalem in 1961, Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann coyly described himself as “just a small cog” in Adolf Hitler’s extermination machine. The German Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt lent credence to this warped view, claiming in Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, published a year after his execution in 1962, that he merely had been a faceless bureaucrat and maybe not even an antisemite.

Arendt’s thesis, which has always been debatable, is torn to shreds by the German writer Bettina Stangneth in Eichmann Before Jerusalem: The Unexamined Life of A Mass Murderer, published by Alfred A. Knopf.

Stangneth bases her argument on a tsunami of source material.

“There are more documents, testimonials and eyewitness reports on Eichmann than on any other leading Nazi,” she writes in the introduction. “Not even Hitler or (Joseph) Goebbels has occasioned more material. And the reason is not simply Eichmann’s survival for 17 years after the end of the war, nor the impressive efforts of the Israeli police in collecting evidence for the trial. The reason is primarily his own passion for speaking and writing. Eichmann acted out a new role for every stage of his life, for each new audience and every new aim. As subordinate, superior officer, perpetrator, fugitive, exile and defendant, Eichmann kept a close eye on the impact he was having at all times, and he tried to make every situation work in his favor.”

While in exile in Argentina, where he lived with his family from 1950 until his abduction by the Mossad a decade later, Eichmann kept meticulous notes. He also submitted to taped interviews conducted by Willem Sassen, a Dutch Nazi who had served in the Waffen SS and in the Third Reich’s ministry of propaganda. Stangneth refers to this trove of 1,300 transcribed pages as the Argentina Papers, which surfaced over the past two years.

In addition, Eichmann left behind about 8,000 pages from his imprisonment in Israel — manuscripts, statements, letters, personal dossiers, ideological tracts, individual jottings and marginal notes on documents.

Having immersed herself in this mountain of documentation, Stangneth draws a compelling portrait of a Nazi careerist who excelled in self-promotion and bending the truth to suit his purposes.

No less a person than Arendt was fooled by him. As Stangneth puts it, “Eichmann in Jerusalem was little more than a mask. She didn’t recognize it, although she was acutely aware that she had not understood the phenomenon as well as she had hoped.”

Facing the death penalty after his capture in a suburb of Buenos Aires, Eichmann, one of the architects of the Final Solution, presented himself as a minor and unimportant SS officer who had been made a scapegoat through error, chance and the cowardice of others. But in conversations with Sassen, who would sell excerpts to Life magazine, Eichmann exalted in his complicity in the Holocaust.

As Stangneth writes, “The extermination of Jews had taken place; he had helped to plan millions of murders — a total genocide, in fact, he still believed this aim to be right; he was satisfied with his part in it; and his only criticism of this lunatic National Socialist project was that ‘we could and should have done more.'”

Eichmann, who organized the logistics of transporting more than 400,000 Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz in 1944, was a liar of monumental proportions. Eichmann’s wife, recalling his parting words before he went into hiding following Germany’s defeat in 1945, told an interviewer: “Vera, I just want to say one thing. My conscience and my hands are clean. I have not killed any Jews, or given a single order to kill. I want to tell you that.”

Technically speaking, Eichmann might have been correct, since he may not have personally murdered a single Jew. But that’s besides the point, of course. Eichmann was in charge of the mass deportations that sent hundreds of thousands of Jews to oblivion in death camps. As Stangneth points out, he regarded Denmark’s heroic resistance to the deportation of its Jewish population as a personal setback.

Eichmann, who joined the Nazi Party in 1932, nearly a year before Hitler’s accession to power, liked to portray himself as an expert in Jewish affairs and Zionism who had been born in Sarona — a German Templar settlement in Palestine — and was fluent in Hebrew.

Stangneth writes, “He is known to have used Sarona very early on, both to impress people in his own camp and to intimidate the Jewish representatives and their milieu.” In fact, Eichmann was born in Solingen, in the Rhineland, and never set foot in Palestine. He spoke no Hebrew and only a bit of Yiddish.

In the same vein, Eichmann claimed he had been best friends with Haj Amin al-Husseini, the Mufti of Jerusalem, who went into exile in Germany, where he met Hitler on two occasions. In Israel, realizing that his fabrication would be counter-productive, Eichmann denied he had ever conversed with the fuhrer.

Argentina had no compunctions about admitting Nazis like Eichmann, Stangneth says. “Argentina was not the only country trying to convince well-educated men to emigrate, but it was one of the few that also provided this opportunity to criminals like Eichmann.”

Old Nazis in Argentina’s well-established German community welcomed Eichmann with open arms, helping him to get on his feet. One of his first employers, Hans Kammler, had been responsible for building concentration camps and extermination facilities in Poland.

In Argentina, Eichmann boasted of his Nazi past and of his rank as an SS Obersturmbannfuhrer. “I was an idealist,” he would say.

By Argentinian standards, he was materially well off. At his last job, the car and truck manufacturer Mercedes-Benz employed him in its warehouse. According to Stangneth, Mercedes-Benz had many German employees during this period, including some who had been members of the SS.

Fritz Bauer, the attorney general of the West German state of Hesse, issued an arrest warrant for Eichmann in 1956, but he was not pursued seriously. Ironically, Eichmann was willing to stand trial in West Germany, assuming he would be treated with kid gloves.

Eichmann was kidnapped by the Israelis on May 11, 1960. His abduction sent shock waves through the German community. “It changed the way they interacted with each other for good. The years of comfortable exile and the natural trust between old allies were suddenly over.”

Eichmann’s lawyer in Israel, Robert Servatius, had no idea that Eichmann had incriminated himself in the Sassen interviews. “His client lied to him about them consistently, from their very first meeting in Israel until the end of the trial,” writes Stangneth.

Eichmann was a liar until the day he was hanged.

Once a liar, always a liar.