From the moment I learned to appreciate fine literature, Ernest Hemingway became one of my favorite authors. I admired his style, his lean, supple, simple, flowing, effortless and evocative prose, which manifested itself beautifully in novels such as For Whom the Bell Tolls and in short stories such as The Killers.

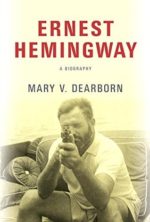

Mary V. Dearborn’s illuminating biography, Ernest Hemingway (Alfred A. Knopf), explores his journey as a novelist and his rich, textured life. It draws on, among other sources, his vast collection of papers and correspondence, as well as his medical records.

Leaving no stones unturned, Dearborn methodically examines every facet of his meteoric career, from his days as a newspaper reporter and foreign correspondent in Kansas City and Toronto to his apprenticeship as a budding author in postwar Paris. On a more personal level, she charts his friendships with famous literary figures running the gamut from Ezra Pound to F. Scott Fitzgerald.

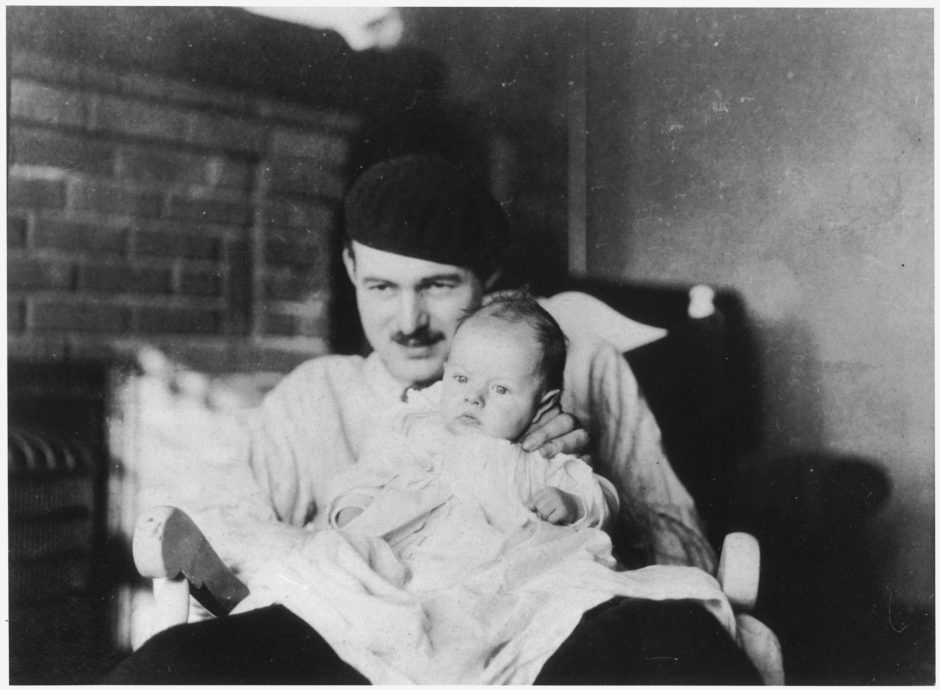

Born in Oak Park, Illinois, in 1899, Hemingway was the scion of solidly middle-class Midwesterners whose conventional lifestyle he abandoned without the slightest qualm. Initially interested in becoming a physician, like his father, he turned to writing and never looked back.

After graduating from high school, he landed a reporting job at The Kansas City Star, one of the best newspapers in the country. There, during the course of seven months, he acquired the elements of good writing. With America’s entry into World War I, he served as a Red Cross ambulance driver in Italy, where he was wounded and fell in love for the first time.

Interestingly enough, he never went to college, an omission in his resume he would regret.

Thanks to a family connection, he obtained an introduction to Greg Clark, the features editor of the Toronto Star Weekly. Recognizing his talents, Clark hired him as a freelancer. His first piece appeared on February 14, 1920. He went on to become a Toronto Star correspondent based in Paris, a job that lasted four years and enabled him to hone his skills as a newspaperman.

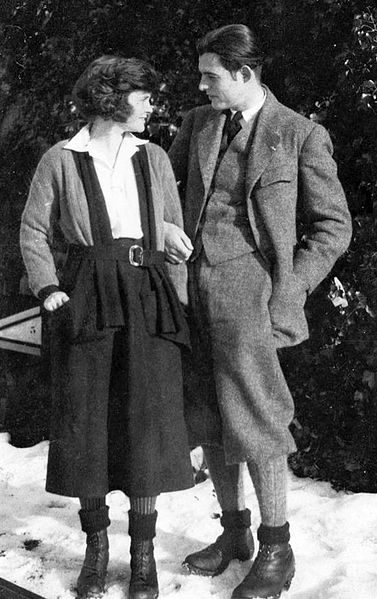

As Dearborn points out, a favorable exchange rate drew Americans to Paris in droves. But Paris also held out the promise of an escape from stifling traditionalist values, sexual freedom (Hemingway was married to Hadley Richardson, his first of four wives, when he arrived in the City of Lights), and unrivalled cultural offerings.

In Paris, Hemingway met up-and-coming writers like John Dos Passos, E.E. Cummings and Ezra Pound, who taught him to be leery of adjectives. Paris was also where he made the acquaintance of Gertrude Stein, who advised him to give up journalism in his quest to be a writer, and of Harold Loeb, an American Jew who would surface in his breakout novel, The Sun Also Rises, under the name of Robert Cohn.

By then, he had plunged into serious writing, having produced short stories ranging from Cat in the Rain to The End of Something, one of his iconic Nick Adams stories.

During this formative period, he formed a lifelong attachment to Spain. “He loved the countryside and he loved the Spanish people,” writes Dearborn. “He loved the fishing, the bullfights, the Catholic shrines and cathedrals, the El Grecos at the Prada, the cafes in Barcelona, the beaches in San Sebastian in Basque Country.” And, she adds, he was fixated by the running of the bulls in Pamplona.

In Dearborn’s view, Hemingway’s fixation with sports — hiking, cycling, boxing, fishing, tennis and skiing — was a function of manic behavior, the classic symptoms of which include excessive energy, racing thoughts and self-destructive tendencies.

Manic or not, his sheer creative energy turned him into a prolific author during his Paris period. In 1924, he wrote eight short stories, including Soldiers’s Home and Mr. and Mrs. Elliot, finished his first novel, The Torrents of Spring, in about a week, and wrote The Sun Also Rises in six weeks. His editor, Maxwell Perkins, called the latter “a most extraordinary performance,” and the critic of the New York Sun exulted, “Every sentence that (he) writes is fresh and alive.”

Buoyed by his early success, Hemingway churned out Men Without Women, a collection of short stories — Hills Like White Elephants, The Undefeated and Now I Lay Me — that Dearborn hails as among his very best. He followed that up with A Farewell to Arms, one of his signature novels, in the late 1920s.

Hemingway earned his reputation as a hard-living, hard-drinking and adventurous macho man through his articles on deep-sea fishing and game hunting in Esquire magazine. In 1936, To Have and Have Not, one of his worst novels, was published. But in that year, his masterful short story, The Snows of Kilimanjaro, also appeared.

Hemingway’s interest in the Spanish Civil War led to a reporting gig in Spain for a syndicated news service and to his longest novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls, which came out in 1940. Dearborn claims that while it is his most tightly constructed novel, it is riddled with “melodramatic flaws.” She says that Robert Jordan, the central character, is an idealized version of himself.

With this novel in hand, critics expected Hemingway to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction. Nicholas Butler, the president of Columbia University, which awarded the prize, vetoed the proposal after asking the jurors to scratch his name off the list of nominees. Dearborn claims that Butler disliked Jordan’s radical politics — Hemingway sympathized with the Republican side in Spain’s war — and the explicit sex in the book. Nonetheless, For Whom the Bell Tolls was commercially successful.

Hemingway covered segments of World War II for Collier’s magazine. His dispatches from the front lines in France in 1944 embellished his self-cultivated image as a man’s man.

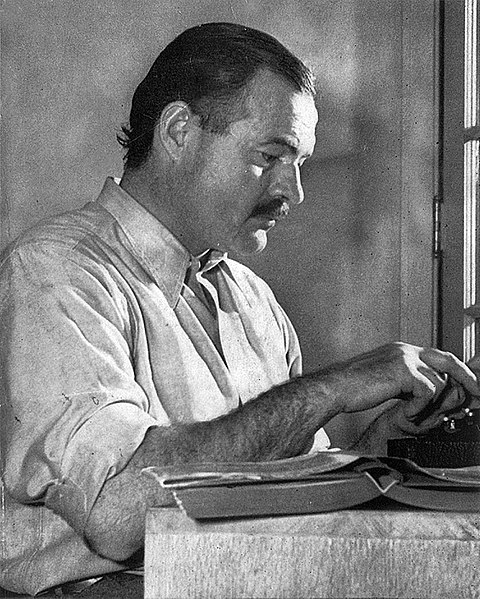

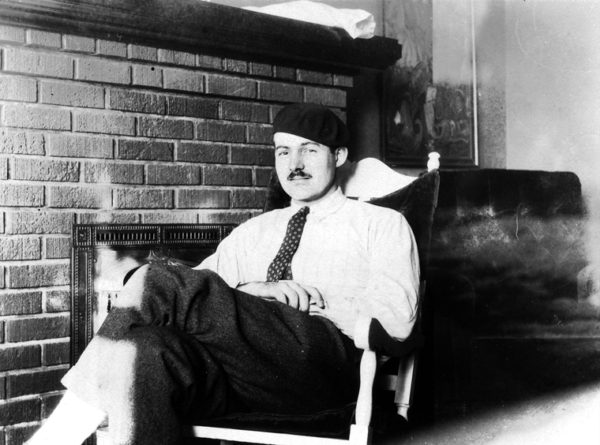

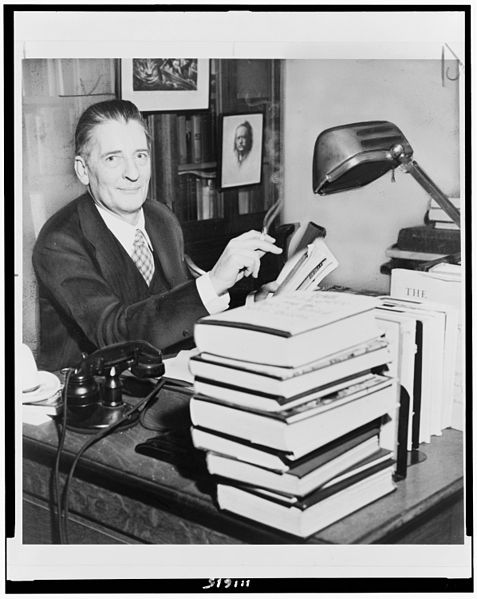

By the late 1940s, he had thickened around the waist, had grayed and was well on his way toward assuming what Dearborn describes as “the famous Papa visage of the 1950s,” caught by the Canadian portrait photographer Yousef Karsh. By that juncture, Hemingway was drinking too much, could not bear to be alone and was prone to temper tantrums and massive displays of egotism. Yet, as Dearborn acknowledges with examples, he could be kind, giving and generous.

With the death of Perkins in 1947, he seemed adrift and temporarily had no idea what to write or what to publish, says Dearborn. A case in point was Across the River and into the Trees, a novel the critics panned. But only two years later, in 1952, The Old Man and the Sea was published to high praise and earned Hemingway the Nobel Prize. Hemingway gathered the material for it in Cuba, where he maintained a villa. After Fidel Castro’s rise to power in 1959, the American ambassador, his friend, urged him to leave the island in a show of disapproval of the new regime. He objected, saying he was unconcerned with politics. But in 1960, he left, never to return.

Dearborn explains Hemingway’s suicide, in 1961 in Idaho, as the culmination of an avalanche of woes. He was not writing well. He was burdened by serious illnesses. He had few good friends. “Soon, no longer able to get the enormous pleasure he had once taken from life, no longer believing in his ability to write, he took his own life,” she says.

Hemingway’s drastic decision to shoot himself was a tragedy whose reverberations are still heard today.