Yale University Press has published two books in its Jewish Lives series for film aficionados — Steven Spielberg: A Life in Films by Molly Haskell, and Warner Brothers: The Making of an American Movie Studio by David Thomson.

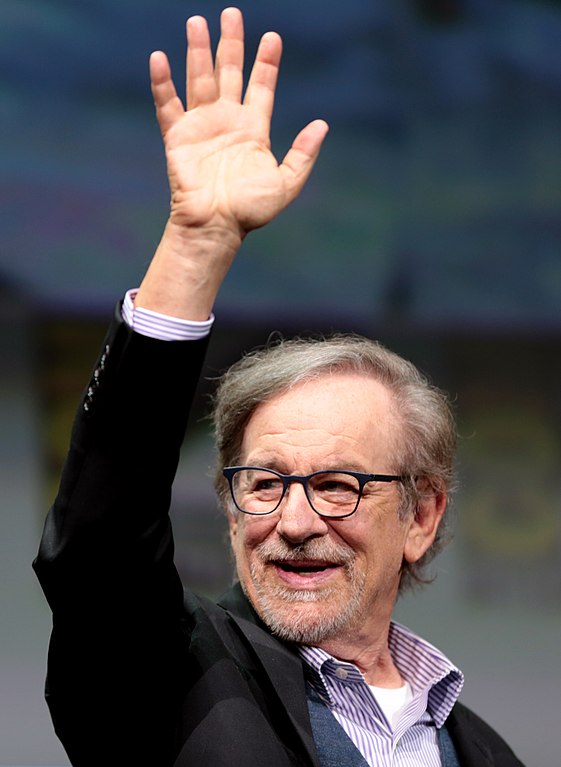

Spielberg, of course, needs no introduction, being one of the most successful directors of his generation. In a 42-year career, he has directed numerous movies, most notably Schindler’s List, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Saving Private Ryan and Jurassic Park. Two of the films, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and Jaws, are among the top ten grossing of all time. He has had box office flops and artistic failures too, including A.I., Minority Report and Catch Me If You Can. But at the end of the day, as Haskell writes in this empathetic biography, “no filmmaker has combined profits and prestige the way he has, with multiple Oscar nominations and wins.”

He was born in Cincinnati, the son of Arnold and Leah Spielberg, whose ancestors immigrated to America from the Russian empire in the first decade of the 20th century. A poor student, he was fascinated by radio and television. Haskell suggests that his father, an engineer, introduced him to cinema when he bought him an 8 millimetre camera. From that point forward, he replaced him as the family videographer, “forgoing the stodgy newsreel style of the home movie genre to reshape, even recreate, reality.”

As a boy and as a teenager, Spielberg wanted only to fit in, but he always fell short, feeling like an outsider until he moved to Los Angeles. Spielberg had a problematic relationship with his Jewish background. He told a biographer “he wanted to be a gentile with the same intensity that he wanted to be a filmmaker.” Like some Jewish men, he had a weakness for Christian women. His second wife, Kate Capshaw, was such a woman. “Maybe I’ve been searching for the ultimate shiksa,” he told an interviewer.

Haskell speculates that Schindler’s List, a film about the Holocaust in Poland, “certified” his “rebirth as a Jew.” She writes, “Spielberg acknowledged that he had now fully confronted his own Jewishness … It meant finding and acknowledging his place in the world.”

By Haskell’s account, he made his first movie while still in the seventh grade. Fighter Squad, an action film set during World War II, underscored his absolute confidence on a set. So dedicated was he to his craft that he faked illness and missed school so he could work on his movies.

Thanks to a family friend, he landed his first industry job at Universal Studios, where he reorganized its movie library. His boss, impressed by his knowledge and enthusiasm, gave him an office, which he shared with a purchasing agent. During this period, he made Amblin, a film about two hitchhikers. It would open doors for him. Sidney Sheinberg, Universal’s vice-president in charge of television, offered him a seven-year contract. He was only 21, the youngest person to a sign a long-term contact with a major Hollywood studio.

His next feature film, The Sugarland Express, turned on a couple bent on reclaiming their baby from a foster home. It was a breakthrough for Spielberg. Pauline Kael, the influential critic, wrote, “He could be that rarity among directors — a born entertainer.”

Jaws, his first big commercial film, opened on more than 400 screens in multiplexes across the United States. Raiders of the Lost Ark became one of the highest-grossing movies. It took him 10 years to decide whether to make Schindler’s List, his most celebrated film. Subsequently, he established the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation, which has collected the stories of 53,000 Holocaust survivors.

During this period, he and two colleagues, David Geffen and Jeffrey Katzenberg, formed Dream Works, a studio they built from the ground up.

Spielberg is close to retirement age, but one can assume he has no plans to quit. Movies are in his blood, as this informative book states.

The Warner brothers — Harry, Albert, Sam and Jack — were a force to be reckoned with in Hollywood. Thomson’s book charts their rise from immigrants to moguls.

By the 1940s, nearly two dozen of their films had been nominated for best picture by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. These included The Life of Emile Zola, Little Caesar and Casablanca. “Warner Brothers had its share of trash,” writes Thomson, “but few of its films were boring or pretentious.”

Some of the brightest stars were on their payroll — James Cagney, Bette Davis, Errol Flynn and Humphrey Bogart, to name but four. Two of its leading actresses, Joan Blondell and Lauren Bacall, were Jewish.

The Warners arrived in America in the late 1880s, fleeing czarist oppression. The family patriarch, Benjamin, was a shoemaker who would run a bowling alley and a butcher shop. His sons went into the movie business after purchasing a kinetoscope, a primitive projector. They drew crowds by screening silent films in parlors and halls. Their first feature film, My Four Years in Germany, based on the memoirs of a U.S. ambassador, was a success.

Harry, the oldest brother, was president of the company and lived in New York City. Jack, the youngest, was in charge of the studio in California from his base in Los Angeles. Albert, living in Miami, was the treasurer. Sam died in 1927.

It was common knowledge that Jack basically ran the show. “It was said he could assess a script in just a few minutes without reading the whole thing,” Thomson says.

The Warners made an impact by churning out 27 films starring the German shepherd Rin Tin Tin. The Jazz Singer, the first talkie, featured the inimitable Al Jolson. During the 1920s, they released sophisticated comedies like Kiss Me Again and So This Is Paris. In the following decade, they captivated audiences with gangster films starring, among others, Edward G. Robinson (born Emanuel Goldenberg in Romania) and George Raft.

The rise of Adolf Hitler did not deter the Warners from distributing films in Germany or maintaining relations with German diplomats in Los Angeles. Georg Gyssling, Germany’s consul in Los Angeles, regularly urged Hollywood studios to be considerate of German sensibilities. When The Life of Emile Zola was still in the script stage, Gyssling demanded that references to Alfred Dreyfus as a Jew should be excised. Jack Warner acceded to his demand. But a few years later, the Warners offended the German government by releasing Confessions of a Nazi Spy, an espionage thriller about an FBI agent (Robinson) who uncovers an extensive Nazi plot in the United States.

Jack Warner, always the dominate figure in the studio, sold it in 1966 to Seven Arts. The transaction netted him $32 million, but as Thomson notes, he was soon lost with so little to do. He died in 1978 after strokes had left him blind and helpless.

Warner Brothers, while interesting, is disorganized. It would have benefited from the blue pencil of a hard-nosed editor.