Mired in an existential crisis, the newspaper industry in Canada and the United States is desperately trying to adapt to changing times. Circulation has tumbled, ad revenue has fallen, newspapers have grown thinner and massive staff reductions have exacted a fearsome toll, as I know from first-hand experience.

The ink-stained wretches — the old-school journalists who love this business — are naturally appalled by these developments. But if they don’t adapt, they will be left behind, cringing bitterly in the dust.

The digital revolution that has eviscerated the print media is still a work in progress, but it’s clearly unstoppable. We can’t stop this, so we might as well go with it. Times change and this is something we either have to accept or stay stuck in the past, which may not be very beneficial to anyone. Doing a bit of research into something as simple as this article can help you understand how you can use technology to your advantage in business.

John Stackhouse, the former editor-in-chief of The Globe and Mail, examines the uncertain state of affairs in contemporary journalism in his thoughtful book, Mass Disruption: Thirty Years on the Front Lines of a Media Revolution, published by Random House Canada.

By turns anecdotal and analytical, Mass Disruption is a cautionary tale of an industry blindsided by the new digital journalism. As the 1980s unfolded, newspapers were fat and complacent, enjoying a virtual readership monopoly and a hold on advertisers that seemed unassailable. Flush with profits, they expanded, not fully realizing that a creeping revolution would undermine their foundations.

Print journalism still exists, but its future is extremely dim due to the emergence of the computer and the ubiquitous Internet that sustains it. “The launch of Facebook, in February 2004, heralded another mass shift that would undo more of the economic underpinnings of traditional media,” Stackhouse says. “The popular news and society site Huffington Post came a year later. Twitter, a year after that, along with Google’s purchase of YouTube in the fall of 2006.” And since then, social media, with its panoply of millions of bloggers, has come into its own.

Cable news TV stations like CNN have altered the media landscape as well. “People no longer needed a paper to tell them what had happened, certainly not what had happened yesterday,” Stackhouse writes in a pithy sentence. “Newspapers (have) to become journals of context and insight.”

In the meantime, popular sites like Craigslist and LeoList hover as the best places to post classified ads, which was the great cash cow newspapers had always depended upon.

Stackhouse, a foreign correspondent and editor of the Report on Business before his appointment as editor-in-chief, gives The Globe and Mail credit for having recognized the importance of digital journalism. In 1995, when the Internet was still in its infancy, it launched globeandmail.com. The Globe and Mail was thus one of the world’s first newspapers to publish in print and online on the same day.

Four years later, Edward Greenspon, a former Globe foreign correspondent, hired a dedicated staff of digital journalists and turned globeandmail. com into a breaking news site. In 2002, Greenspon was appointed editor-in-chief of The Globe and Mail. When Stackhouse succeeded him in 2009, he began moving the newsroom to a “digital-first model, with a focus on mobile and short-form video.”

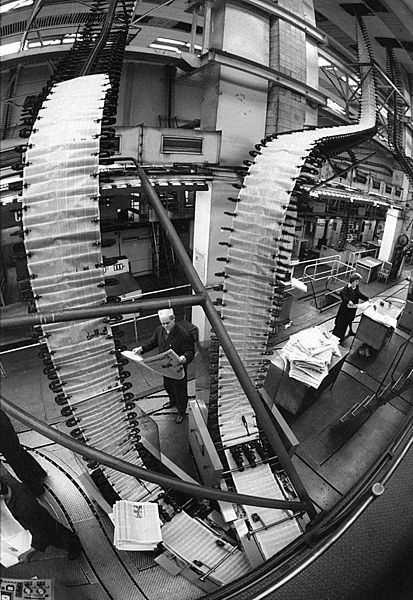

Online journalism makes perfect sense, though I personally like the tactile feeling and smell of a freshly-printed newspaper. It eliminates in one fell swoop the expensive machinery of traditional journalism — printing presses, newsprint and a fleet of delivery trucks and drivers to deliver newspapers. It’s a substantial saving that no publisher can ignore.

As Stackhouse suggests, some staffers have not been able to adapt to the digital era. When he asked political columnist Jeffrey Simpson to write three rather than four columns a week and shift some of his efforts to an online audience, he balked in anger.

By contrast, Stackhouse singles out Guy Crevier, the publisher of La Presse — Quebec’s largest newspaper — as a pioneer of digital journalism. Recently, La Presse became the first major newspaper to transform itself into an online publication, except on Saturday. By 2020, the print version of La Presse will be phased out altogether, he notes.

Stackhouse acknowledges that the digital age makes more demands on journalists. “In the print era, the workhorses of a newsroom might produce 150 or so stories a year. By 2010, with mobile and digital platforms updating stories through the day, we stopped counting at 400. Most staff wrote at least 50 percent more stories than they had when they were published only in print.”

Digital journalism, however, has created huge job losses. The Globe and Mail itself has laid off reporters, photographers and one film reviewer and taken to using cheaper freelancers and even outsourcing copy editing.

Shamelessly enough, some freelancers are not even paid. “We hoped the unpaid writers would see it as a trade: their content for access to our audience,” he says disengenuously.

In his judgment, newspapers will never be as big as they were in the 20th century, perhaps not even a fraction of that size.

Stackhouse is ambivalent about the quality of digital journalism. Much of it, he says, doubtless referring to sites such as Buzzfeed, has become “a blend of the racy yellow tabloids of the 1890s and the provocative, self-absorbed New Journalism of the 1960s.” But a handful of the digital startups have begun to generate excellent journalism, he says, citing a few examples.

In any case, he observes, the smartphone has reshaped the craft, having become a “dominant force” almost overnight. Americans’ use of smartphones and other mobile devices currently account for 23 percent of their media time, up from four percent four years ago.

Peering into the future, he predicts that consumers will soon have to pay for what is now virtually free — quality digital journalism. The paywall was always inevitable. No surprise here.

Mass Disruption has its lighter moments, too. Stackhouse recalls his days as a reporter posing as a homeless person on the streets of Toronto to highlight the growing problem of homelessness.

And he devotes several pages to an encounter with Russian President Vladimir Putin. After he and a group of world editors had interviewed Putin at his home on the outskirts of Moscow, Stackhouse asked if he could accompany him to his regular pick-up hockey game. “Why not?” Putin said. Putin, driving a late-model sports car, drove Stackhouse to an ice arena in Moscow. Stackhouse joined the game, in which Putin, naturally, emerged as the top scorer.

Later, the players repaired to a bar upstairs and were treated to Putin’s favorite dishes — fresh crabs, sardines, shrimp and salmon, all flown in from Siberia.

Not a bad way to end a long day in the trenches of journalism.