The current map of the Middle East is an artificial construct, having been conceived and drawn up by European colonial powers during a period of tumult, dissolution and intrigue.

As a result of the upheavals unleashed by the outbreak of World War I, the Ottoman Empire lost its territorial foothold in the Arab world. This tectonic process unfolded in a few short years, creating new realities. The world’s greatest Islamic empire crashed. The new nation state of Turkey emerged. A succession of sovereign Arab countries, like Syria, Lebanon and Iraq, appeared. The Jewish state of Israel was established in what had been Palestine.

Eugene Rogan, a British historian, places these momentous events in historic perspective in The Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East, published by Basic Books. It’s a first-class account of the unintended consequences of war. The Ottomans staked their fortunes on a military alliance with Germany, hoping to ward off Russian aggression and protect their far-flung possessions. It was a catastrophic miscalculation, proving yet again that wars can make fools of the wisest strategists.

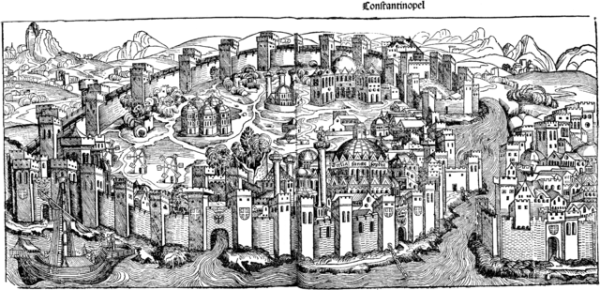

As Rogan points out, the Ottoman Empire had been in retreat long before the eruption of the war in 1914. Having emerged as the supreme power in the Mediterranean basin after capturing Constantinople in 1453, the Ottomans proceeded to add Syria, Egypt and the Red Sea province of Hijaz to their domains. In 1529, the Ottoman army under the command of the sultan, Suleyman the Magnificent, reached the gates of Vienna.

But from the 18th century onward, the Ottomans beat a retreat, losing ground to Greek, Romanian, Serbian and Bulgarian national movements in the Balkans. During the next century, Britain seized Ottoman territory in Cyprus and Egypt, France occupied Tunisia and Russia annexed three provinces in the Caucasus.

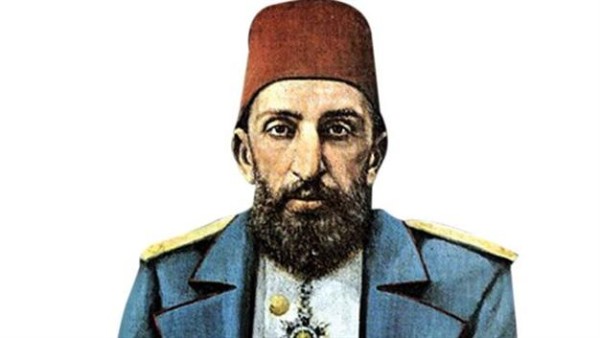

In a desperate bid to staunch the decline, a group of army officers, calling themselves the Young Turks, staged a revolt against the autocratic reign of Sultan Abdulhamid II, but left him on the throne.

From 1908 to 1913, Rogan notes, turmoil ensued as reformers attempted to bring the empire into the 20th century, Ottoman armies fought a series of Balkan wars and Arab and Armenian activists clamored for more autonomy.

A new Young Turk leadership emerged in 1913. Consisting of Talat Pasha, Enver Pasha and Cemal Pasha, this triumverate would determine the fate of the empire. Surveying the political landscape, they saw Russia as their most dangerous adversary. They were right. Russia sought Istanbul, the European shores of the Bosporus, the Sea of Marmara and the Dardanelles.

Since neither Britain nor France could be counted on for help to rein in Russia, the Young Turks turned to Germany, an old friend. Germany, harbouring imperial ambitions in the Middle East, was interested in building a railway from Berlin to Baghdad, and had already dispatched a general, Otto Liman van Sanders, to assist in the reform and reorganization of the Ottoman armed forces.

Convinced that a defensive alliance with the Germans could guarantee the territorial integrity of the empire, the Young Turks signed a secret treaty with Germany on August 2, 1914. Much to their satisfaction, Germany promised to fend off Russian designs.

As Rogan observes, the Young Turks would have preferred to remain neutral until a German victory seemed assured, but Germany pressured them to join the war much sooner. Many officers in the German high command, he claims, believed that the Ottomans could best contribute to the war effort by sowing jihad among Muslims in British and French colonies. The Young Turks had their own agenda, the recovery of lost territory.

Although the Ottomans took the military initiative on three fronts from December 1914 to April 1915, they fared poorly on the battlefield. At Gallipoli, however, they turned the tide, stunning the British and the French.

Suspecting Armenians of supporting and collaborating with Russia, the Ottomans perceived the Armenian community as a dire threat. In a massacre of immense proportions, Armenians were deported and murdered, their political and cultural leadership decapitated.

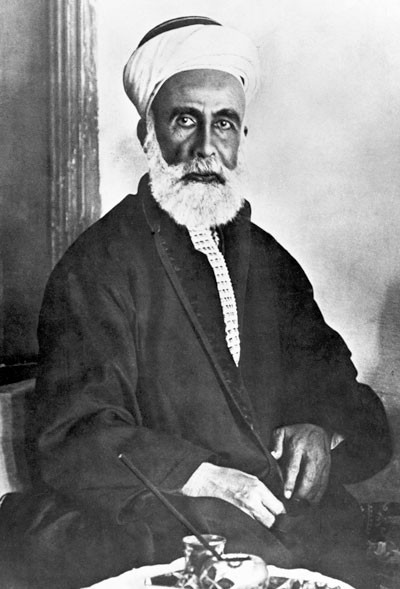

Much to the displeasure of the Young Turks, Sharif Husayn of Mecca, until then an Ottoman loyalist, forged an alliance with Britain in an attempt to attain Arab independence. Little did he know that Britain and France, in the 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement, had divided the Middle East to suit their own purposes. The Sykes-Picot accord, says Rogan, was “an outrageous example of imperial perfidy.”

T.E. Lawrence, a British army officer in the Arab Bureau, entered the picture as the Arab Revolt against the Ottomans picked up a head of steam.

For the Young Turks, 1917 was a disastrous year.

Britain conquered the Sinai Peninsula, but was repulsed in the Gaza Strip, at least in the first two offensives. Australian troops captured Beersheba in the largest cavalry charge of its kind. The British government issued the Balfour Declaration, promising Jews a “national home” in Palestine. The declaration would invigorate the Zionist movement. Shortly afterward, the Ottoman garrison in Jerusalem surrendered to British general Edmund Allenby, bringing to an end 401 years of Ottoman rule in the city. Meanwhile, Syria and Lebanon fell.

Hostilities on the Middle East front ended on October 31, 1918, with the Ottomans having gained absolutely nothing. Two weeks later, British, French, Italian and Greek forces took possession of Istanbul. In the following year, Italy landed troops in Antalya and Greece occupied Izmir.

Under the settlement ending the war, Britain and France were rewarded with mandates in Palestine, Syria, Lebanon and Iraq. Parts of Anatolia, the Turkish heartland, were to be handed over to Armenians, Greeks and Kurds.

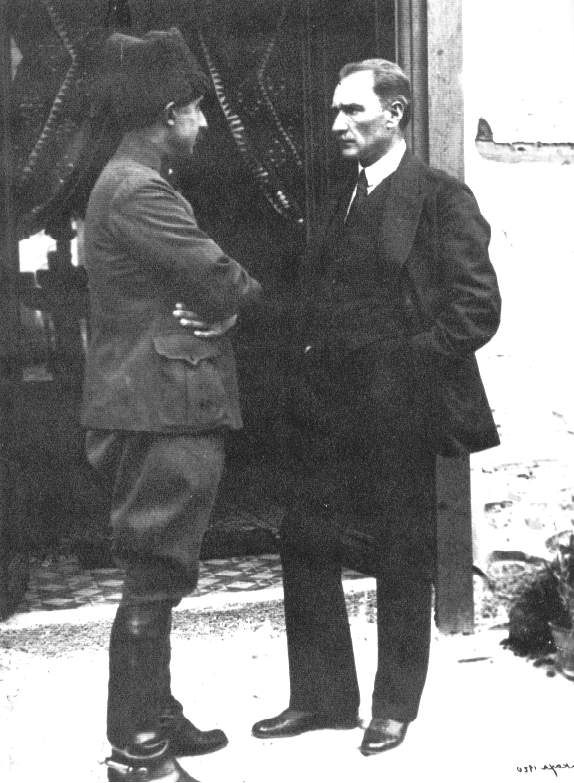

Mustafa Kemal, a Turkish general, objected to his country’s dismemberment and mounted a campaign of resistance. The sultan, rejecting Kemal’s nationalist zeal, charged him with treason. Kemal pressed on, defeating the Armenians in the Caucasus, the French in Cilicia and the Greeks in western Anatolia.

Under the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, Turkey’s independence was recognized more or less within its present boundaries. By then, the Turkish Grand National Assembly had voted to abolish the sultanate. The last sultan, Mehmed VI, was sent packing into exile.

In retrospect, World War I unleashed uncontrollable forces that created a new geopolitical order in the Middle East. Rogan, in The Fall of the Ottomans, charts and explains these developments with rigor and panache.