Since the 1980s, Chinese people have displayed “unprecedented levels” of interest in Jews and Israel, says Zhou Xun, a scholar at the University of Essex. This phenomenon has manifested itself in the proliferation of Jewish studies programs and the publication of books on Jewish history.

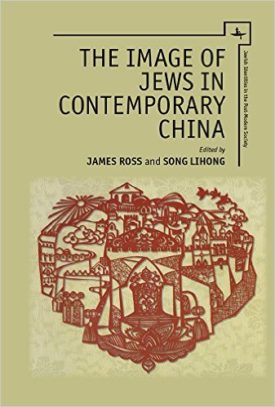

Xun’s essay appears in The Image of Jews in Contemporary China, an illuminating volume edited by James Ross and Song Lihong and published by Academic Studies Press. It’s one of the informative essays by Chinese and Western scholars that deal with such overlapping topics as Chinese perceptions of Jews, the ancient Jewish community of Kaifeng, Jewish and Holocaust studies in China, and China’s relationship with Israel.

Having travelled to China several times in the past 13 years, I’m drawn to this subject, and glad to say this book covers a great deal of ground in comprehensive fashion.

In an introductory essay, Ross — a Northeastern University historian — suggests that dollars and cents lie at the core of China’s “discovery” of Jews. “As the Chinese economy surges, Jews represent money, power and success, goals to which most Chinese aspire,” he explains.

Xun elaborates on this theme: “In modern China, the definition of ‘Jew’ and ‘Jewishness’ is problematic and complex. It is a symbol for money, deviousness and meanness; it can also represent poverty, trusthworthiness and warmheartedness.” She adds, “The Jew can be a filthy capitalist or an ardent communist …” Jews embody “negative as well as positive qualities.”

As Xun observes, Chinese researchers have inadvertently embraced antisemitic tropes to understand Jews. You Xiong, a celebrated writer, claims that Jews “control” world politics and finance due, in part, to their rational thinking and good judgment. “The symbolic link between Jews and money has reemerged especially in cities such as Shanghai and Harbin,” Xun says.

Ross, in another essay, contends that Chinese scholarly interest in Jews, known as “youtai,” dates back to the early 19th century, when Protestant missionaries translated the Christian Bible into Chinese. Turning to the wave of books about Jews published in China, he points out that they’re filled with “misunderstandings and stereotypes.” Some are almost comical. Tian Zaiwei, in What’s Behind Jewish Success, writes that “Jews are distinguished by their noses.”

Glenn Timmermans of the University of Macau explores this point. “It is precisely because China sees Jews, often rather stereotypically, as, on the whole, an admirable people who have survived continuous persecution and great suffering and still maintain a strong sense of their own identity, that they do wish to know more about this small but noteworthy nation.”

Xu Xin, in Chinese Policy Toward Kaifeng Jews, writes that Kaifeng Jewry enjoyed a relatively high degree of religious freedom during the Middle Ages. “Over time, Jews in Kaifeng did not lose their identity, even when they were not observant and their community ceased to formally exist,” he says.

During the Republican period, from 1912 to 1949, some 40,000 Jews lived in China, Its founding father, Sun Yat-sen, endorsed Zionism, saying Jews “rightly deserve an honorable place in the family of nations.” During the Holocaust, China was “particularly sympathetic to the plight of Jews” and permitted European Jewish refugees to enter Shanghai, says Xu, a professor at Nanjing University.

Israel’s bilateral relations with China are examined by She Gangzheng of Brandeis University in The Changing Image of the State of Israel in People’s Daily in the Cold War.

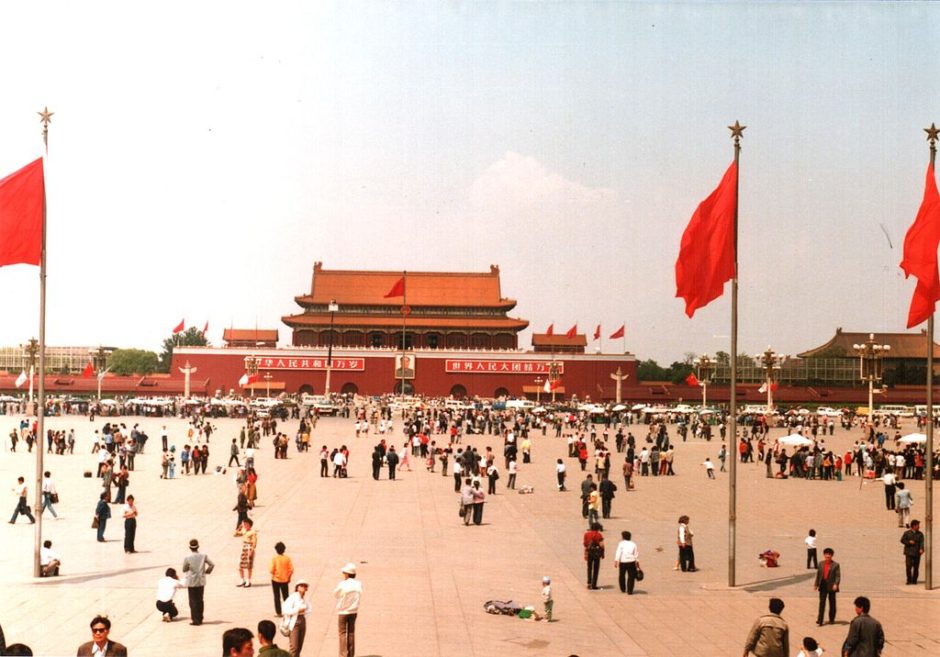

From the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 until 1991, China and Israel did not have formal diplomatic ties. During this era, China was sometimes quite hostile to Israel. From 1948 to 1954, China’s attitude to Israel, as reflected in the People’s Daily, the official organ of the Communist party, tended to be positive. Israel was regarded as a “peace-loving” and “courageous” nation.

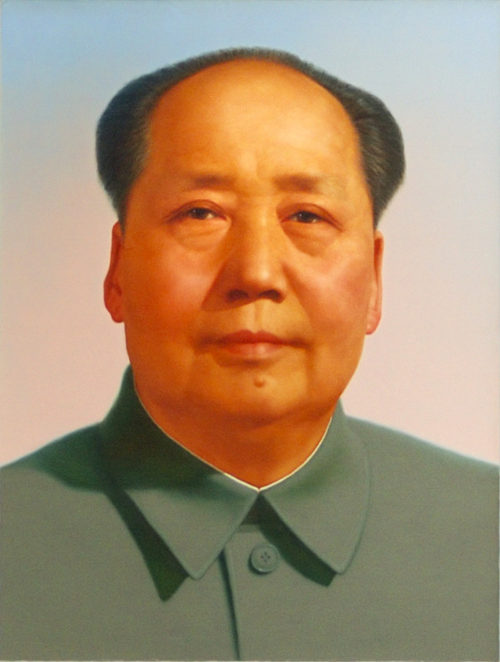

But in the wake of the 1955 Bandung Conference of non-aligned countries, China shifted to a pro-Arab position. Israel’s image was also battered by the 1956 Suez crisis. In 1965, Mao Zedong, China’s supreme leader, told a PLO delegation that “Israel, like Taiwan, is one of the military bases of American imperialism.”

From the Six Day War onwards, the People’s Daily adopted a still more critical stance toward Israel, labelling it a “proxy of the United States.”

With Mao’s death and the advent of Deng Xiaoping’s pragmatic leadership, the newspaper began to carry positive articles about Israel. This trend accelerated in the 1980s, even though China continued to be pro-Arab.

Before Deng’s appearance on the scene, there was little academic research on Israel. Since the late 1970s, Israel studies have made “considerable progress,” says She.

Chen Yi, in an essay on Israeli-Chinese relations, reminds readers of a salient fact: Israel recognized the People’s Republic of China in 1950, but the two countries failed to establish formal relations. Still, China never officially rejected Israel’s existence.

As China normalized links with Israel, Israeli arms and technology flowed to Beijing. But there were glitches. Example: Israel agreed to sell China the Phalcon, a sophisticated reconnaissance aircraft, but the United States vetoed the deal, forcing Israel to compensate China to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars.

China’s cultural relationship with Israel has yielded concrete dividends, says Zhiqing Zhong in The Reception of Contemporary Literature in China. At last count, 114 books and anthologies have been translated from Hebrew into Chinese, including the writings of S.Y. Agnon, Aharon Applefeld and A.B. Yehhoshua. Amos Oz, however, remains the most widely translated and recognized Hebrew writer in China.

No less than 10 Chinese institutions of higher learning grant degrees in Jewish history, philosophy, religion and culture, discloses Song Lihong. “What’s more, articles on Jewish topics are increasingly well represented in learned journals.”

According to Timmermans, the founders of Jewish studies in China are Xu Xin of Nanjing University and Pan Guang of the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences.

Holocaust studies are a comparatively new field in China, but the Holocaust looms larger there than in any other country in Asia for two reasons, as Timmermans explains: the Chinese experience of Japanese atrocities during World War II and China’s role in granting refuge to German and Austrian Jews during the same period.

This surge of interest in all things Jewish among Chinese people is no minor development, and fortunately, it’s neatly encapsulated in The Image of Jews in Contemporary China.