I was a young man when the Six Day War broke out on June 5, 1967, a date stamped indelibly into my memory. In the life of a person, there are only a handful of select events that one never forgets, and the Six Day War is one of them.

On that warm, sunny morning in Montreal, when I was about to start a summer job, I turned on the radio to listen to the 8 a.m. CBC news report. The first item exhilarated me. The Israeli Air Force had launched a preemptive strike on Egyptian airfields and had destroyed a significant proportion of Egypt’s planes. On the ground, Israeli armored columns had penetrated Egyptian lines and were advancing swiftly into the Sinai Peninsula toward the Suez Canal.

When I returned home, I tuned in to Walter Cronkite’s 6:30 p.m. newscast on the CBS television network. In incredulous tones, he reported Israel’s stupendous victories in the air and on land. I was elated and euphoric, as was my father, who had been a soldier in the Polish army when Germany invaded Poland on the first day of World War II.

The outbreak of the Six Day War came as something of a relief, dramatically defusing a tense, nerve-wracking three-week waiting period during which Israel’s Arab enemies menacingly massed on its borders and threatened it with annihilation.

The countdown to war, I believe, began on May 14 when the Soviet Union — the first country to recognize the newly-created state of Israel in 1948, but now a staunch ally and generous arms supplier of Arab countries — issued a false report of an Israeli military buildup on the Syrian border. Tensions had been escalating since Israeli pilots shot down six Syrian MIGs in a dogfight on April 7 and Israel’s chief of staff, General Yitzhak Rabin, made threatening comments about Syria.

Egypt’s top soldier, General Mohammed Fawzi, flew to Damascus to confirm the rumor that had been circulated by Moscow, but found no trace of Israeli troops massing on Syria’s frontier with Israel.

Nonetheless, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser — a secular Arab nationalist who had fought in the first Arab-Israeli war and who could not abide Israel’s existence — continued stirring the pot. On May 21, he demanded the removal of the United Nations Emergency Force in the Sinai, which had been established to patrol the demilitarized peninsula following the 1956 Sinai War.

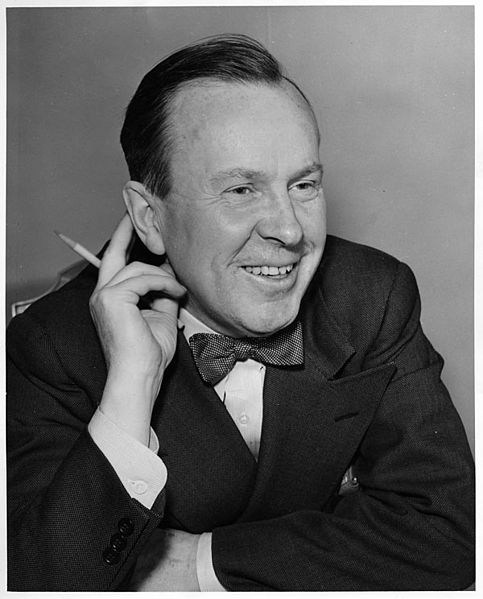

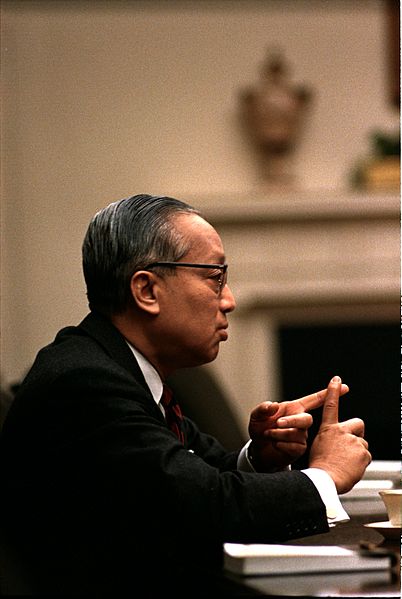

The notion of inserting an international peacekeeping force to stabilize the region had been proposed by Canada’s foreign minister, Lester B. Pearson, and now it was fast unravelling, thanks in part to U Thant, the United Nations secretary-general who acceded to Nasser’s demand all too hastily. U Thant’s show of weakness emboldened Egypt to dispatch two armored divisions to the Sinai, thereby shattering the status quo and planting the seeds of a new war.

On May 22, Nasser raised the ante again when he announced the closure of the Strait of Tiran, in the Gulf of Aqaba, to Israeli shipping. Israel regarded this provocative move as a casus belli, since the Gulf of Aqaba was its maritime gateway to the Far East. Nasser understood he had crossed a red line, but he was defiant. “We are ready for war,” he said in a fiery speech.

Four days later, Nasser declared that his chief objective would be “the destruction of Israel” if hostilities broke out. Nasser’s confidant, Mohammed Hassanein Heikel, the editor of Al Ahram, wrote in his column that war was inevitable.

In the face of this jingoistic rhetoric, Egypt and its Arab allies recklessly continued to push the region to the brink.

On May 30, King Hussein of Jordan, who had maintained secret contacts with a succession of Israeli prime ministers since his ascent to the Hashemite throne, signed a defence pact with Egypt. On May 31, an Egyptian general arrived in Amman to take charge of what would be the eastern front. On June 4, Egypt entered into a defence agreement with Iraq.

Buoyed by the mood of triumphalism sweeping the Arab world, Iraqi President Abdel Rahman Aref said, “We are determined and united to achieve our clear aim: to remove Israel from the map. We shall, Allah willing, meet in Tel Aviv and Haifa.”

The drumbeat of Arab threats demoralized some Israelis, who feared another Holocaust was in the offing. In Tel Aviv, young men began digging thousands of graves in parks. One of these volunteers was Benjamin Netanyahu.

The gloom lifted after the appointment of Moshe Dayan as minister of defence. Dayan, a dashing and resolute figure who had been chief of staff of the armed force in the 1950s, inspired more confidence than the stolid prime minister, Levi Eshkol. Amid these fast-moving developments, Rabin suffered a nervous breakdown, from which he swiftly recovered.

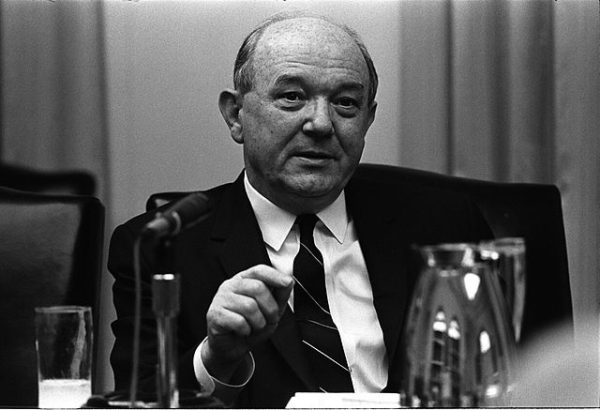

The Israeli government appeared indecisive as tensions mounted. Abba Eban, the foreign minister, advised cabinet ministers that the international community expected restraint from Israel. Dean Rusk, the U.S. secretary of state, said that while the United States would try to reopen the Gulf of Aqaba to Israeli shipping, Washington would remain neutral “in thought, word and deed.”

Israeli generals, however, were chomping at the bit. “We must wrest the initiative from the Egyptians,” said Avraham Yoffee. “What are we waiting for?” asked Matti Peled. “We’re ready, and we’ll destroy the Egyptian army,” said Ariel Sharon.

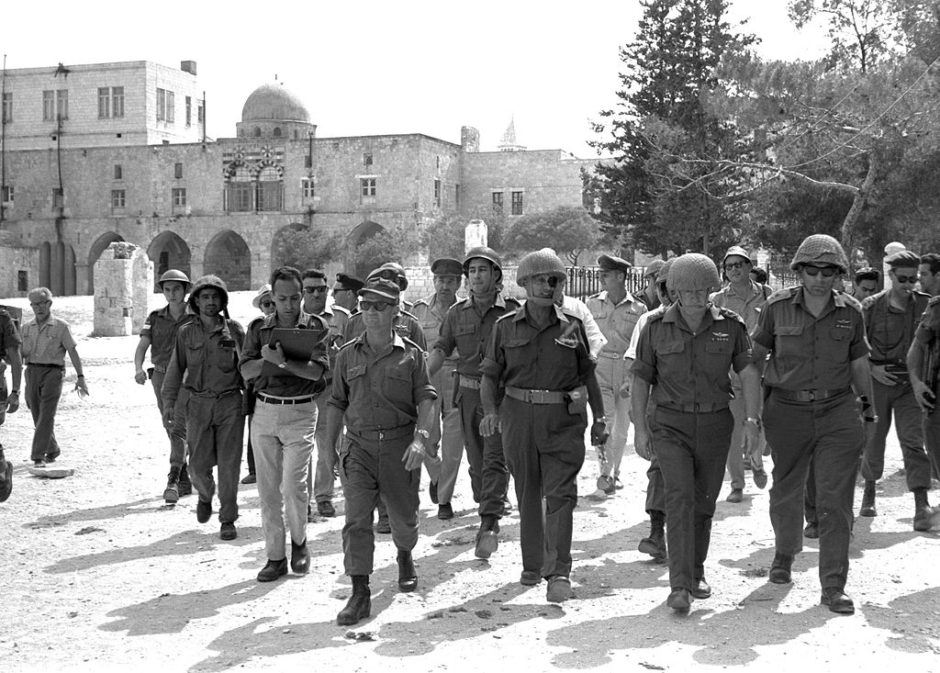

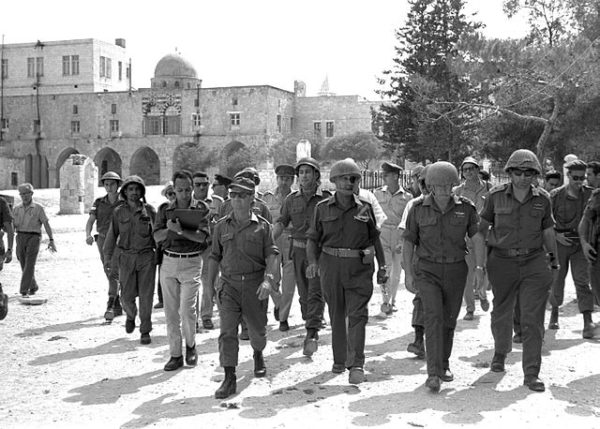

Israel broke the wrenching impasse with blistering air strikes that virtually obliterated the Egyptian Air Force in three hours. And in a blitzkrieg, Israeli tanks pushed into the Gaza Strip and deep into the Sinai. By the third day, Israeli troops Egypt had reached the Suez Canal.

Although Israel had warned Jordan to stay out of the war, King Hussein did not heed that advice. Jordanian artillery bombarded western Jerusalem and the suburbs of Tel Aviv, prompting an Israeli offensive to capture East Jerusalem and the West Bank.

Syria fired rockets into the Galilee, staged air raids and launched an attack on Kibbutz Dan. Israel responded by attacking Syrian fortifications on the Golan Heights. An Iraqi aircraft bombed Netanya. By way of reaction, Israeli jets struck a base in western Iraq.

Within a week, Israel had conquered territory in Egypt, Jordan and Syria, thereby tripling its size. The Arab world was utterly humiliated and pan-Arabism was discredited.

In retrospect, it’s clear that the Soviets set off the chain of events that culminated in the war. Nasser exploited them for his own ends, but he may have been grandstanding, not expecting such an outcome. Years later, Eban wrote, “Nasser did not want war. He wanted victory without war.”

War is what Nasser got in spades, but having been rearmed by Moscow, Egypt initiated the War of Attrition against Israel in the Sinai shortly after its defeat. Costing Israel dearly in terms of lives lost, the war ended with a ceasefire worked out by the United States in 1970. In 1973, the Yom Kippur War erupted as Egypt and Syria tried to regain the Sinai and the Golan. Israel’s complacency was shattered into a thousand pieces.

Shortly after the Six Day War, Israel established its first settlement in the occupied areas on the Golan. Israel would build more settlements on the Golan, the West Bank, Gaza and the Sinai. Years later, amid an acrimonious debate, Israel relinquished the Sinai and Gaza. But in the West Bank and the Golan, Israel built an array of new settlements and expanded existing ones.

The settlement project, championed in particular by the right-wing Likud Party after its election triumph in 1977, would become a source of contention inside Israel and an object of fierce criticism outside its boundaries. Israel’s deeply-entrenched occupation has polarized Israeli society and earned Israel the enmity of nations.

In the wake of the Six Day War, Israel annexed East Jerusalem and environs, creating a “united and indivisible” capital. Not a single nation has recognized the annexation. As for the Palestinians, they claim eastern Jerusalem as their rightful capital of a future Palestinian state.

The Six Day War galvanized the Palestinian national movement, imbuing it with a much stronger sense of nationhood. Hardly demoralized by the stunning Arab defeat, the Palestinians, led by Yasser Arafat, launched an insurrection in the West Bank. It was summarily crushed by the Israeli army and the Shin Bet, Israel’s internal security agency.

The Palestinians, having regrouped in Jordan, attacked Israeli towns and villages near the Jordan River. Jordan was dragged into the fighting. The Palestine Liberation Organization was driven out of Jordan in 1971, only to relocate to Lebanon. From that point onward, Israel and the PLO were locked in mortal combat in Lebanon until the PLO was chased out of the country following Israel’s 1982 invasion.

Undeterred by these setbacks, the Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza rose up in rebellion against Israel in the intifadas of 1987 and 2000, which claimed numerous lives in waves of terrorism. The Palestinians are still at odds with Israel, but Egypt and Jordan signed peace treaties with Israel in 1979 and 1994, respectively.

As a result of the Six Day War, the United States greatly upgraded its bilateral relations with Israel, which became a regional super power. The process, begun by President Lyndon Baines Johnson, was extended by his successors, whether Republicans or Democrats. Israel and the United States share not only moral and political values, but enjoy a strong strategic relationship. Washington and Jerusalem, however, remain at odds over Israeli settlements in the West Bank — a legacy of the Six Day War.

Five decades have elapsed since the eruption of the war, but the problems and dilemmas it created still resonate.