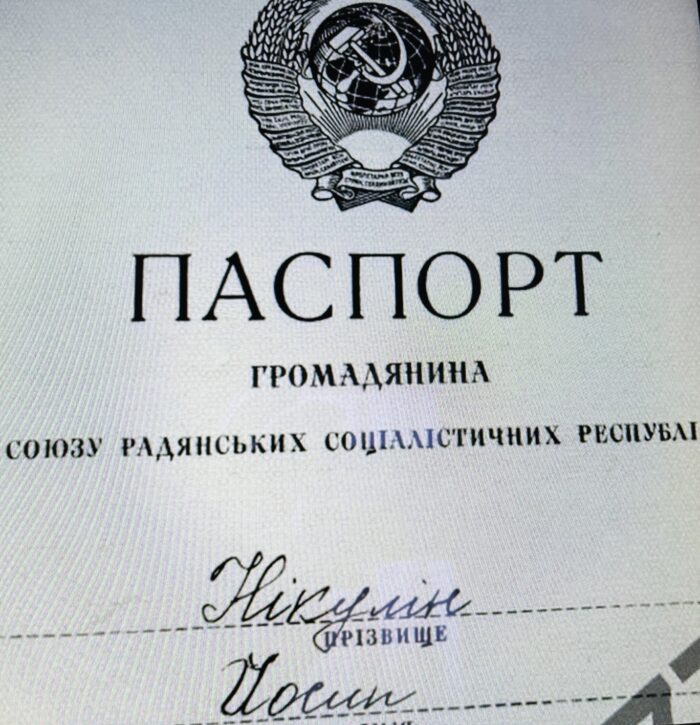

At the age of 16, citizens of the now-defunct Soviet Union received their official identification card. This was usually seen as a festive and significant event, a giant step forward into adulthood.

One’s “nationality” was inscribed on the fifth line of this document. In a multicultural country with 100 nationalities, you could be Russian, Ukrainian, Latvian, Lithuanian, German or Jewish. And therein lay a problem of immense importance to Jews. Once you were officially identified as a Jew, your social, economic and occupational horizons were automatically limited.

In short, the fifth line in your internal passport singled you out and, if you were Jewish, determined your prospects and fate in Soviet society.

This was particularly true after the birth of Israel in 1948. While the Soviet Union was one of the first countries to recognize Israel’s existence, Moscow feared that Jews might be more loyal to Israel than to the motherland. Since the Soviet communist regime under Joseph Stalin’s leadership suspected Jews of dual loyalty, the fifth line in their ID card predetermined their status in nearly every conceivable way.

This issue is explored in some depth in 5th Paragraph, an Israeli documentary by Boris Maftsir and Lilia Tsvokbenkel. It will be screened on June 3 at this year’s edition of the Toronto Jewish Film Festival, which runs from May 30 until June 9.

Their interviewees are Soviet Jews who immigrated to Israel in two separate waves — from the late 1960s onward and from the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. During this period, when immigration restrictions were lifted, more than one million Soviet Jews immigrated to Israel, the United States and Canada.

In the main, 5th Paragraph is about its ramifications. As the Soviet Union’s bilateral relations with Israel cooled in the 1950s, Jews were subjected to greater restrictions. The fifth line was incorporated into Soviet documents in 1932 and abolished in 1997, but oddly enough, the filmmakers gloss over these facts.

When the pro-Arab Soviet Union severed diplomatic relations with Israel during the 1967 Six Day War, the position of Soviet Jews grew still more fraught.

Although Soviet citizens were theoretically equal under the law, Jews ruefully described themselves as “Paragraph 5 invalids” and observed a code of silence regarding their Jewish ancestry.

The interviewees in this unsettling film recall their childhood years in schools with anguish. To an alarming degree, they were picked on and ridiculed by their classmates simply because they were Jewish.

When Jewish students applied for places at universities, they were often rejected. A quota system kept the vast majority of Jews out of elite educational institutions. The diplomatic corps was resolutely closed to Jews, and Jews could generally not advance beyond a certain rank in the armed forces.

Antisemitism remained a malignant sore in the Soviet body politic despite government slogans that promoted the brotherhood of humanity. “You could feel the antisemitism in the air,” says a woman.

By this point, Jewish culture had been largely suppressed by the authorities, and Zionism was constantly blasted as an imperialist ideology.

In 1970, with Moscow having staunchly sided with the Arab world against Israel, the Soviet regime forced 52 prominent Jews to denounce Israel at a notorious press conference. Among them were David Dragunsky, an army general, and Maya Plisetskaya, a famous ballerina.

A process of political and economic liberalization occurred under Mikhail Gorbachev’s rule of glasnost and perestroika, enabling Jews to leave in droves. But during this interregnum, antisemitic agitators emerged into the full light of day.

5th Paragraph covers much of this material in a rather glib and superficial manner, failing to provide viewers with a rigorous sociological analysis of religion and ethnicity in the Soviet Union.