The first group of Jews to be transported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp in Poland consisted of 999 women from Slovakia. Their gruesome story unfolds in Heather Dune Macadam’s empathetic documentary, 999: The Forgotten Girls, which is scheduled to be screened at the Toronto Jewish Film Festival on May 31.

Slovakia, a province of Czechoslovakia, seceded in 1938. Its fascist president, Jozef Tizo, was a virulent antisemite and an admirer and ally of Adolf Hitler. He presided over the passage of anti-Jewish legislation more severe than that of even Nazi Germany.

In the spring of 1942, the Slovakian regime, having already expropriated the property of Jews, revoked their citizenship, pushing them one step closer to deportation.

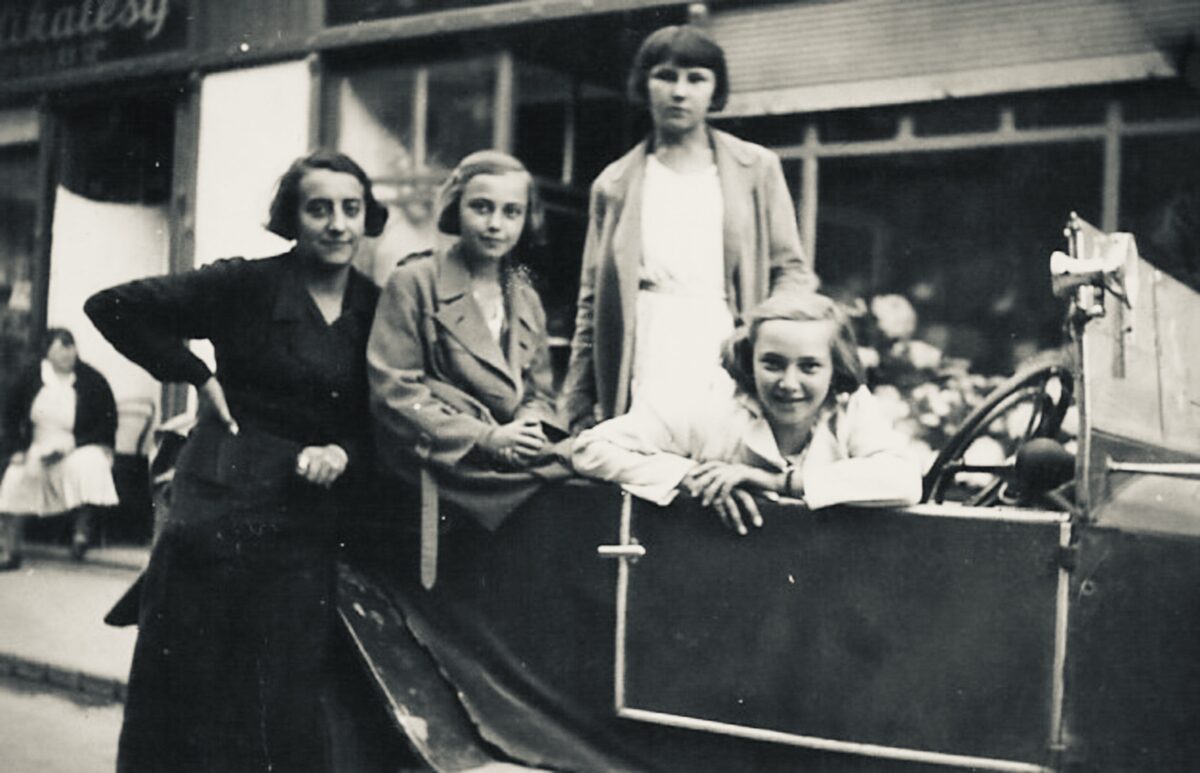

Prior to these events, 999 unmarried Jewish women over the age of 16 were rounded up for labor service on the orders of Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS. They assumed they would be back home within six months.

Taken to the Slovakian town of Poprod, they were dumped in an empty army barrack, then loaded on a train headed for Auschwitz-Birkenau. Appearing on screen, survivors say they had no idea where they were going. “We didn’t know what was waiting for us,” a woman says.

They reached the death camp on March 26, 1942, thinking they were in a grim factory complex. Placed in charge of the new arrivals were 999 German female kapos.

Housed in rudimentary barracks bereft of bunk beds and crawling with bedbugs, they were immediately mistreated by guards, who forced them to strip and submit to intrusive inspections of their private parts.

Compelled to wear the bloodied uniforms of Russian prisoners of war for the next six months, they were put to work demolishing the walls of condemned buildings on the grounds. Two women who were injured during this back-breaking and dangerous task were shot on the spot by the SS.

Several months later, the first transport of Slovakian Jewish deportees pulled into Auschwitz-Birkenau. Most were almost immediately gassed, the fate that befell some of the very first deportees.

A typhus epidemic killed still others. The lucky ones were put to work in Kanada, a vast storehouse containing the looted personal possessions of deceased Jewish prisoners.

On January 18, 1945, nine days before the Red Army liberated the infamous camp, the last remaining girls were forced on a Death March during a snow storm. As one woman recalls, the road was littered with corpses.

Eventually, they were placed on the open coal wagons of a train bound for the Ravensbruck concentration camp in Germany, which was reserved for females. Their new “home” was a terrible place. Women died of starvation. The luckier ones subsisted on spoiled horse meat. Thousands of prisoners were gassed.

The film does not disclose how many of the 999 Slovak women survived, but it appears that most died. After the war, some survivors were sent to neutral Sweden, where they received a warm welcome. A few returned to Slovakia, only to find that no one was waiting for them. The Slovakian Jewish community had been all but decimated.

In general, the survivors resettled in Israel, the United States and Canada. Many got married before leaving Europe.

This little-known footnote in the annals of the Holocaust has been expertly explored and now takes its rightful place in the anthology of films examining this human catastrophe.