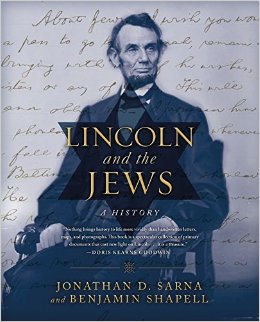

Historians never tire of reflecting on Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States. Since his assassination 150 years ago, just days after the Civil War had ended, he has been probed and analyzed in an avalanche of some 16,000 books.

With all this ink having been spilled in the cause of scrutinizing an iconic figure, one can ask if anything new can be said of Lincoln, a great leader and a courageous politician who guided his nation through war and liberated African Americans from the shackles of slavery.

Surprisingly, perhaps, there are gaps still to be filled in this vast terrain of historiography. Unlike his 19th century predecessors, Lincoln had a “profound and unusual relationship with Jews,” according to Jonathan D. Sarna and Benjamin Shapell, the authors of Lincoln and the Jews: A History, published by Thomas Dunne Books.

Its publication coincides with the launch of a major exhibition on Lincoln at the New York Historical Society. To See Jerusalem Before I Die — Lincoln and the Jews opened on March 19 and closes on June 7. It will then move to museums in Springfield, Illinois, Boston, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, Chicago and Los Angeles.

By all accounts, this handsomely-illustrated book is only the third or fourth volume of its kind in the past century. Theirs, however, is the most comprehensive, based on newly discovered documents and years of painstaking research.

To the best of their knowledge, Lincoln, born in Kentucky in 1809, never met a Jew until he was an adult. By that point, the United States was home to a mere 3,000 Jews. But Lincoln, an avid reader of the Bible, was certainly not unaware of Jews.

Jews in early 19th century America enjoyed legal equality. The first president, George Washington, promised them religious liberty as an “inherent right.” Yet Jews stood apart from the Christian mainstream and were widely considered foreigners. In a letter to John Adams in 1813, Thomas Jefferson made a denigrating reference to Jews, decrying their “wretched depravity of sentiment and manners.”

Lincoln, a lawyer, probably met Jews for the first time during his years in Springfield. “He came to know them as neighbors, clients and political allies,” Sarna and Shapell write in this sweeping survey of his friendship with Jews. “By the time of his death, he had acquired far more Jewish friends and acquaintances than any other American president before him.”

As Lincoln himself once said, “I myself have a regard for the Jews.”

Lincoln’s closest Jewish friend, Abraham Jonas, was born in Britain in 1801 and immigrated to the United States when he was a teenager. Like Lincoln, Jonas served in the state legislature. Lincoln also knew Julius Hammerslough, one of the nation’s largest clothing manufacturers, and Louis Salzenstein, a shopkeeper and livestock trader whom he represented in a minor lawsuit. Salzenstein, they speculate, may have been the first Jew Lincoln ever met.

Among his other friends and acquaintances were Issachar Zacharie, a chiropodist who treated Lincoln for back, wrist and foot problems and who was dispatched on a secret mission to the Confederacy, and Abraham Kohn, a staunch fellow Republican who sent him an American flag with Hebrew inscriptions.

Lincoln, in 1862, appointed Jacob Frankel as the first Jewish military chaplain in U.S. history. But as Sarna and Shapell point out, Lincoln’s frequent definition of Americans as “Christian people” remained problematic.

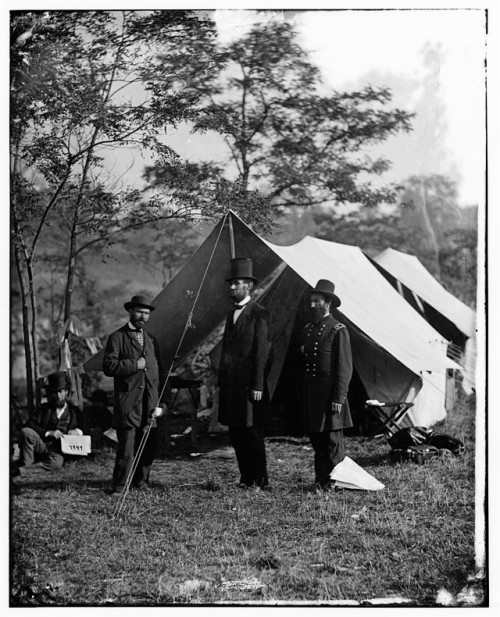

Nevertheless, when Union general Ulysses S. Grant issued General Orders 11 expelling “Jews as a class” from his district in Mississippi, Tennessee, Kentucky and Illinois, Lincoln intervened and rescinded the infamous edict.

Grant, a future American president, ordered Jews out of his area of command after several Jewish cotton smugglers and speculators were caught engaging in illegal activities. Cesar Kaskel, a resident of Kentucky, was affected and outraged by this unprecedented expulsion order. He contacted his congressman, who introduced him to Lincoln.

Lincoln, then in the midst of writing his famous Emancipation Proclamation, had not been aware of Grant’s order, and immediately quashed it. “I do not like to hear a class or nationality condemned on account of a few sinners,” he explained.

Sarna and Shapell claim that Lincoln’s interactions with Jews form part of a much larger history. As they put it, “It is, in microcosm, the story of how America as a whole began to come to terms with its growing Jewish population and how Americans and Jews were changed by that encounter. ”

In short, they add, Lincoln “promoted the inclusion of Jews into the fabric of American life and helped to transform Jews from outsiders to insiders.”

Lincoln’s willingness to embrace Jewish Americans as insiders paralleled his efforts to abolish slavery and grant legal equality to black Americans, they note.

After his murder, northern Jews eulogized Lincoln, lauding him for his character, values, leadership abilities and faith. And as Sarna and Shapell observe, they played a “significant role” in shaping America’s portrayal of Lincoln.

Southern Jews, however, did not generally mourn his passing.

Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, was hardly a philosemite. He described David Levy Yulee, a Florida senator, as “a contemptible Jew.” And he castigated Judah Benjamin, the confederacy’s secretary of state, for having belonged to “that tribe that parted the garments of our Savior.”

In 19th century America, there was only one president like Abraham Lincoln, at least as far as Jewish Americans were concerned.