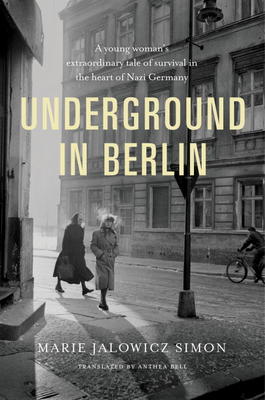

Facing increased harassment and persecution, several thousand German Jews still in Berlin after the outbreak of World War II went into hiding. Marie Jalowicz Simon was one of these so-called “submarines.” Living under an assumed name and shuttling between a succession of safe houses, she survived the tyranny of Nazism by the skin of her teeth.

Long after Simon’s ordeal had ended, her son, Hermann, asked his mother to recount her story on tape. Out of this has come Underground In Berlin: A Young Woman’s Extraordinary Tale of Survival in the Heart of Nazi Germany, published on May 12 by Alfred A. Knopf Canada.

Simon was a rarity among German Jews. The majority emigrated following Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in 1933. The ones who stayed behind hoped for the best, but were subjected to increasingly harsh and humiliating restrictions and, finally, deportation to Nazi extermination camps in Poland. Others, like Simon, took matters into their own hands and effectively disappeared from sight.

Simon was born in Berlin in 1922, the daughter of Hermann and Betti Jalowicz. Her mother died a few months prior to the Kristallnacht pogrom in November 1938. Her father, a notary, passed away in 1941, six months before the Nazi regime enacted legislation outlawing the emigration of Jews.

In the spring of 1940, when the German juggernaut seemed unstoppable and invincible, Simon became a forced laborer in the armaments industry. “We did hard physical work,” she recalls of her days as a worker in a Siemans plant. Even as she learned to adjust to this “abnormal situation,” she was beside herself with “rebellious feelings, crying out silently for liberty.”

In the wake of her father’s death, she was compelled to vacate his apartment. She found accommodation with a Jewish family in a slum area. Simon’s aunt, Grete, was deported to Lodz, a city in Poland, in 1941. She was advised to go with her, but a sense of self-preservation held her back.

As a Jew, Simon was permitted to go food shopping only in the late afternoon, when everything had already been sold out. In defiance of this Nazi edict, she went in the morning, the mandatory yellow Star of David visible on her coat. Stopped on the street and reprimanded by a minor Nazi official one day, she was almost arrested.

Conditions worsened toward the close of 1941. “The threat of danger settled round my neck like a noose and kept tightening,” she writes, referring to the ethnic cleansing of Jews. “Fear had me in its clutches.”

In desperation, she decided to marry an Asian man, thinking that his Chinese passport would protect her from the wrath and machinations of the Nazis. “My Chinese fiance was a nice man, and generous,” she recalls. “He gave me presents now and then. But we did not come any closer. After all, we could hardly converse with each other.” Their relationship petered out, leaving Simon vulnerable once again.

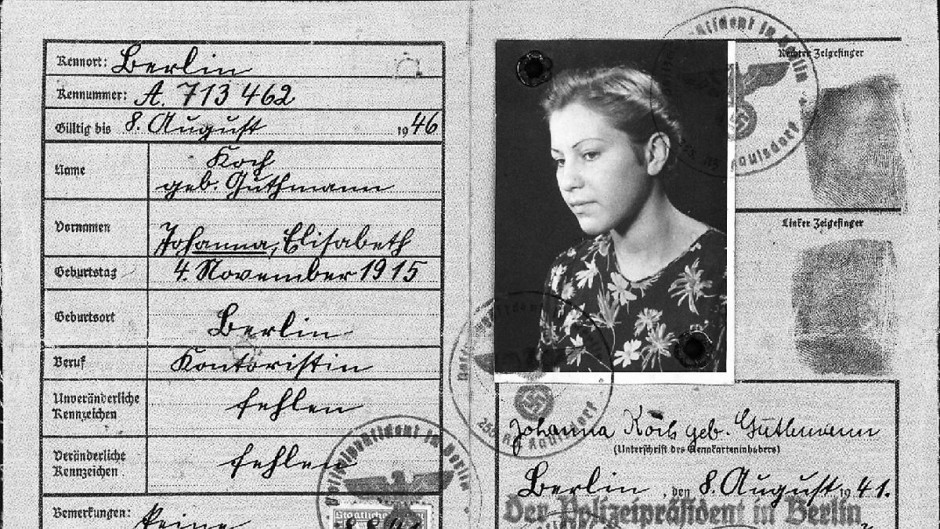

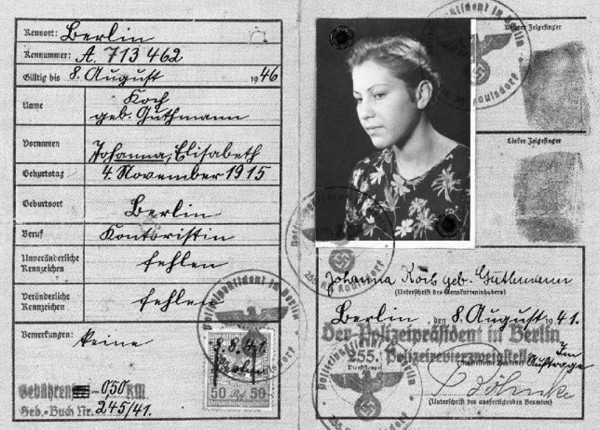

In 1942, thanks to German friends, she acquired a false identity card under the name of Johanna Elisabeth Koch. During these forlorn years, she found refuge in 20 different safe houses, staying with foreign workers, communists and even a Nazi, who behaved like a mother figure. “Life is complicated,” she observes in an understatement.

Concluding she would be better off in another city, Simon went to Magdeburg. “As soon as I arrived, I stood out as a stranger. I drew an important conclusion: if I wanted to live underground without hiding all the time, I could do so only in Berlin.”

Still, she was always at risk, dodging not only zealous Nazis but Jewish informers like Stella Goldschlag and Rolf Isaakson, who worked for the Gestapo in exchange for their lives.

Though heartened by the July 1944 assassination plot against Hitler, Simon had no illusions. “They were not really anti-fascists but conservative military men,” she says dismissively of the plotters.

Like all Berliners, she feared Allied bombing raids. Yet she was not afraid of what was coming — Germany’s defeat. When she learned that Germany had surrendered unconditionally, she rejoiced. “I stood formally by the side of the defeated, but my feelings were with the victors,” she says.

As the Soviet army swept through Germany in April and May 1945, thousands of women were brutally raped. “Naturally I was among them,” she discloses in a curt aside.

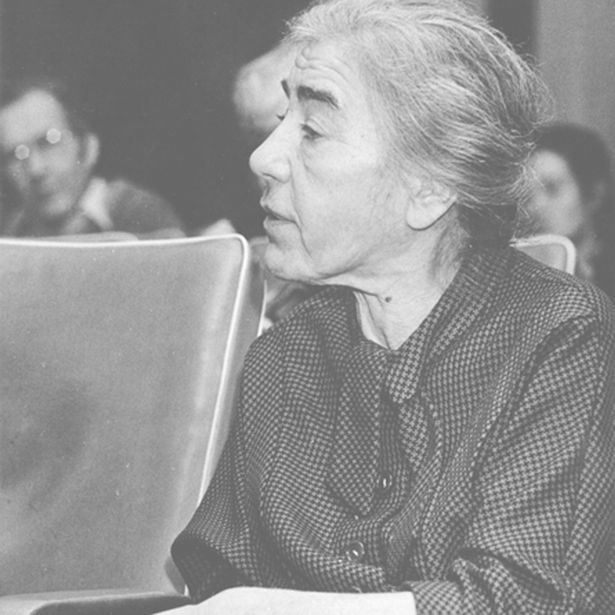

After the war, Simon studied philosophy and sociology at the University of Berlin and joined the Communist Party. She married Heinrich Simon, an academic who taught classical Arabic and Arab philosophy at Humboldt University. Simon herself was a professor of ancient literature and cultural history at the same institution.

She died in 1998, leaving behind this heart-felt testament of survival in the Nazi bastion of Berlin.