Anwar al-Awlaki was a lucky guy, at least until his luck ran out.

Born into an elite Muslim family from Yemen, he was a member of the lucky sperm club. His father, Nasser, was a government minister and president of a university. Anwar, his son, was superbly educated and possessed the gift of the gab. He could have gone far had he not been sucked into the vortex of Islamic radicalism. But having joined Al Qaeda and having inspired or encouraged his followers to attack the United States by violent means, he marked himself for death.

On September 30, 2011, he had the dubious distinction of becoming the first American citizen since the U.S. Civil War to be hunted down and killed by his government.

Scott Shane, in Objective Troy: A Terrorist, A President, and the Rise of the Drone (Random House), tells his story in methodical and lucid fashion.

The order to kill Awlaki was issued by Barack Obama, a president who sought to improve relations between the United States and the Muslim world. “He believed the Bush administration had done grave and unnecessary damage with its counter-terrorism policies and with the invasion of Iraq,” writes Shane, a New York Times reporter specializing in national security affairs.

Yet under the Obama administration, the United States stepped up the pace of drone strikes aimed at Muslim extremists in Yemen, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

As Shane suggests, Awlaki was an unlikely terrorist.

He was born in 1971 in New Mexico, where his father, a secular Arab, was a graduate student in agricultural science at New Mexico State University. In 1977, the Awlakis returned to Yemen, where he grew into manhood. Awlakai showed no special interest in Islam, though he was intrigued by the concept of jihad.

Returning to America, he studied civil engineering in Colorado while serving as an imam at the Denver Islamic Society. He preached tolerance, denounced Al Qaeda and condemned the terrorist events of September 11, 2001, during which the World Trade Center in Manhattan was brought down in a hail of smoke and rubble.

But after the United States launched its war on terrorism, sweeping up scores of American Muslims in its net, Awlaki criticized the roundups. “This is a war against Muslims,” he declared.

As he became increasingly militant, he grew a beard, an unmistakable sign of his surging religiosity. As a preacher, he complained about the plight of the Palestinians, U.S. support for Israel and the sanctions that had been imposed on Iraq.

In Shane’s estimate, Awlaki’s break with the United States occurred in 2005 with the release of Constants on the Path of Jihad, a five-hour set of lectures which have been described as perhaps the single most influential work of jihadist incitement in English. In these lectures, he lauded Sayyid Qutb, a member of the Egyptian Brotherhood who was hanged in 1966 on charges of attempting to assassinate Egypt’s president, Gamal Abdul Nasser.

By then, he was publicly calling for the mass murder of Americans in the name if jihad and describing the United States as a “nation of evil.”

Claiming that 9/11 had been “the answer of the millions of people who suffered from American aggression,” he articulated his inflammatory message in a blunt, clear and informal style that attracted numerous followers. By that point, Awlaki had been identified as the single most dangerous threat to the United States by the American government.

His advocacy of violence had become open and unconditional by 2009, says Shane. Awlaki, having become proficient in disseminating his message on the Internet, was complicit in a plot by a Nigerian Muslim man to blow up an American airliner. He also inspired Nidal Hassan, a U.S. army officer, to open fire on fellow soldiers at Fort Hood, Texas. And he influenced the Toronto 18, a group of Canadian Muslims bent on storming Canada’s Parliament and beheading the prime minister.

In some of his sermons, Awlaki — a married man with children — railed against zina, or licentious behavior. But as Shane points out, he was a rank hypocrite, frequenting prostitutes. “Sometimes he asked for intercourse, sometimes oral sex and sometimes he just watched the woman stimulate herself while he masturbated.”

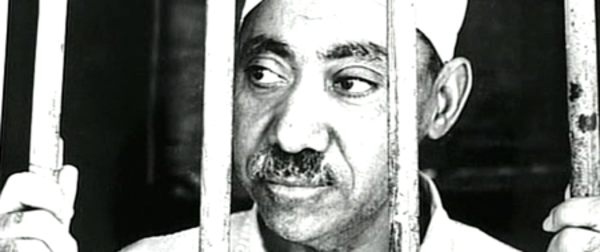

In 2006, he was arrested in Sanaa — the capital of Yemen — and thrown into prison, charged with having participated in an Al Qaeda plot to blow up oil installations in Marib and Hadramout provinces.

Obama placed him on a kill list in 2010, and the Central Intelligence Agency offered a $5 million reward for his capture.

Predator drones spotted him in a pickup truck in a remote area of Yemen and fired two or more missiles, but missed the target. Shortly afterward, a Reaper drone equipped with Hellfire missiles killed him.

“Never before in history had the U.S. government’s awesome power been directed to hunting and killing a single citizen,” Shane observes. “It was simultaneously a triumph of technology, an act of self-defence in the relentless American campaign to eliminate the risk of terrorist attack, and, in the view of some, a challenge to the (U.S.) constitution and to the legal and ethical standards on which Americans prided themselves.”

Obama called his death “a major blow to Al Qaeda’s most active operational affiliate.”

But to his followers and admirers — young, restless Muslims searching for a cause — Awlaki is nothing less than a martyr to be emulated. And today, though he’s deceased, he speaks to them through his sermons and videos.

Awlaki’s ideology and finesse in recruiting acolytes, Shane adds, has served as a model for Islamic State, the Sunni jihadist organization seeking to create a caliphate in the Middle East.

Awaki is dead and buried, but his legacy lives on, as Shane points out in his informative book.