When I visited Warsaw in the summer of 2009, the Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews, a monumental $100 million project, was still a figment of the imagination of its founders and still in the planning stages.

When I returned to Poland last month, Warsaw’s newest museum had been opened for more than a year and was already a great tourist attraction, drawing in a steady stream of visitors and brightening up an otherwise drab cityscape of gray apartment buildings in the city’s former Jewish neighborhood, Muranow.

An impressive glass and copper structure facing a 1948 monument honoring the Warsaw Ghetto uprising — which broke out on April 19, 1943 — the museum brilliantly chronicles the 1,000-year history of Jews in Polish lands.

Its chief curator, Barbra Kirshnenblatt-Gimblett, is a Canadian of Polish Jewish ancestry.

Polish Jewry was virtually wiped out by Nazi Germany in a genocidal onslaught which began with its invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939. Within a few years, the German occupiers had eradicated more than 90 percent of the 3.3 million-strong Jewish community, which was second in size to that of the United States.

Polish Jews never really recovered from this catastrophe. According to the Polish census of 2011, Poland’s official Jewish population is only about 7,000.

It’s a community that’s a pale imitation of its former self, judging by the stunning collection of artifacts, photographs, posters and documents in the museum’s eight galleries.

Even a cursory tour leaves a visitor with the distinct impression that Jews left an indelible mark on Poland. As the museum’s glossy pamphlet succinctly states, “The history of Polish Jews is an integral part of the history of Poland …”

The galleries are found beneath the airy first floor foyer and are reached by way of a white marble staircase that leads to a phalanx of green screens portraying an unspoiled forest of pine and deciduous trees.

According to legend, the first Jews to reach Poland called it Polin, its Hebrew name. “Po,” in Hebrew, means “here,” while “Lin” means “shalt thou dwell.” Supposedly the first known Jewish traveller to set foot on Polish soil was a trader/diplomat from Moorish Spain, Ibrahim Ibn Yakub. “It abounds in food, meat, honey and arable land,” he wrote in Arabic.

The oldest object in the museum, a coin engraved with Hebrew letters, was minted in the 13th century by Jewish craftsmen. Under the Statute of Kalisz, Jews had been given permission to settle in Poland by Boleslaw the Pious.

Exhibits trace the settlement of Jews in the country and document the relationship between Polish kings and their Jewish subjects. Seven hundred thousand Jews lived in Poland during the era of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a golden age for Jewish communal autonomy and rabbinical authority and scholarship. A large map pinpoints the towns where Jews resided.

The world’s first Yiddish books were printed in Krakow in the mid-16th century, one of the obscure facts that comes to light as you wander through the halls.

Although it accentuates the positive, the museum does not recoil from documenting darker interludes, such as the 1648 Khmelnytsky uprising-cum pogrom, which devastated Jewish communities and left the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in ruins.

It would be no exaggeration to say that the intricately-painted timber ceiling of an 18th century wooden synagogue is the museum’s piece-de-resistance.

These exquisite wooden shuls, built in towns and villages where Jews comprised a large proportion of the population, were methodically destroyed by the Germans in a frenzy of hatred. The ceiling, as well as the equally magnificent bimah, were reconstructed by a cadre of craftsmen and students.

Poland lost its independence during the partitions of the late 18th century, and as a result of this national tragedy, the Jewish population of Russia, Prussia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire increased significantly. These developments are traced by means of interactive exhibits and paintings.

Jews played a key role in the 19th century industrialization of Poland. Entrepreneurs like Herman Epstein and Jan Bloch built the first railways, while Izrael Poznansky was one of the founders of the textile industry in the central Polish city of Lodz. (One of his descendants, Alicia Poznansky, was married to Jacques Parizeau, a leader of the separatist Parti Quebecois).

Polish Jews experienced hardships in the late 19th century. With pogroms erupting in the Russian empire from the 1880s onward, Jews emigrated en masse. According to a chart in the museum, some two million Jews left between 1881 and 1914, with the overwhelming majority immigrating to the United States. Canada attracted 105,000, or four percent, of the immigrants. Seventy thousand, or three percent, settled in Ottoman Palestine.

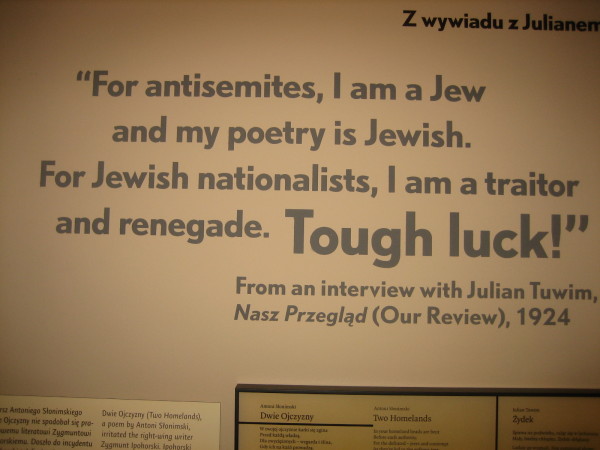

Poland attained independence in 1918, and for a while, the Jewish community flourished under the banner of the Second Republic. Economic turmoil and rising antisemitism, however, cast a dark shadow. The mood of this mercurial epoch is conveyed by graphic posters and photographs and a pungent quotation from the assimilated Jewish poet Julian Tuwim decrying racism.

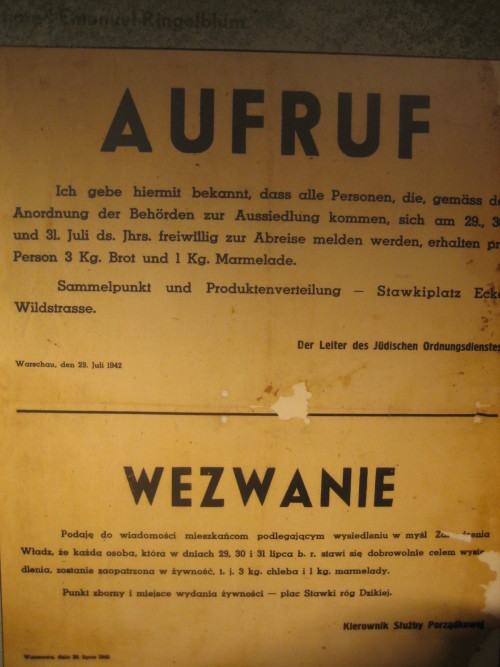

The Holocaust, the darkest period in the annals of Polish Jewry, fills a visitor with dread and sadness. Excerpts from the diaries of Emanuel Ringelblum speak to the growing repression of Jews within Nazis ghettos.

A Nazi sign promises bread and jam to Jews who report for “resettlement” in what would be the Treblinka extermination camp.

Nazi propaganda photographs portray the roundup of Jews after the fall of the Warsaw ghetto. On May 6, 1943, Jurgen Stroop, the German general in charge of destroying the ghetto, wrote, “The Jewish quarter in Warsaw is no more.”

Jan Karski’s role in publicizing the genocidal intentions of the Nazis is noted. Karski, a courier from the Polish government-in-exile who visited the Warsaw ghetto before its destruction, is commemorated by a statue outside the museum building.

The number of European Jews deported to Nazi concentration camps is inscribed on a plaque. From seven Jews in Finland to 2.9 million Jews in Poland, the toll was staggering.

A touching photograph of a survivor kissing the hand of a British soldier who liberated her in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in 1945 ushers in the postwar era in Europe.

The rebirth of Jewish life in Poland in the wake of World War II was rocky. The 1946 pogrom in Kielce drove away Jews in droves, as did the 1968 state-sponsored anti-Zionist campaign. An excerpt from an indignant article by Mieczyslaw Rakowski, the editor of the journal Polityka, denounces the anti-Jewish witchhunt.

The revival of the Jewish community in democratic Poland after 1989 opened a new and hopeful chapter in Polish Jewish history. This phase is documented at length, but has yet to play itself out. The museum will doubtless take note of it in due time.