Rzeszow, the largest city in southeastern Poland, is a paradigm for inconsolable loss.

Like scores of Polish towns, cities and villages where Jews were demonized, marginalized and murdered by the Nazis during the Holocaust, Rzeszow lost an important part of its multicultural heritage with the destruction of its substantial Jewish community.

On the eve of Germany’s invasion of Poland, on September 1, 1939, Rzeszow’s population stood at approximately 42,000, of whom 12,000 to 14,000 were Jews. Prior to the Holocaust, Poland was home to 3.3 million Jews. Only the United States had a greater number of Jews.

At the end of 1941, the 20,000 Jews of Rzeszow and surrounding districts were crammed into a horseshoe-shaped ghetto near Market Square, the city’s scenic focal point.

Starting in the summer of 1942, when the Jewish inhabitants of the Warsaw ghetto were subjected to the first wave of mass deportations, the Jews of Rzeszow were successively deported to the Belzec extermination camp, shot in the nearby Rudna forest and sent to the Peikinia concentration camp and the Szebnia forced labor camp.

In the autumn of 1943, the last remaining Jews were dispatched to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Some 600 Jews from Rzeszow escaped to the Soviet Union. One hundred survived in Poland, hiding in dense forests or in the homes of peasants brave enough to offer them sanctuary.

When the war ended, the traumatized Jewish survivors left Poland, bound for Palestine, the United States and other destinations.

Dariusz Mazurek, a local guide, claims that 200 Poles in the area were executed by the Germans for having lent a helping hand to fleeing Jews.

The annihilation of Rzeszow’s Jewish community, which took place within a span of five years, ended a 500-year Jewish presence in the city. In Nazi parlance, Rzeszow was rendered Judenrein, like many other places in Poland.

When I asked Mazurek whether any Jews still live in Rzeszow, 300 kilometers from Warsaw, he replied, “I know a few Poles of Jewish descent, but there is no organized Jewish community here.”

Jews settled in Rzeszow in the 15th century, but as elsewhere in Europe, they were subjected to various restrictions. Nonetheless, Jewish traders and merchants dominated the local economy.

The first shul, known as the Old Synagogue, was erected in the 17th century. Another shul, the New Synagogue, was built about two centuries later.

This region, dotted with picturesque farms, was annexed by the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the late 18th century and not handed back to Poland until the advent of Polish independence in 1918. Before Poland was partitioned by the Austrians, Russians and Prussians, Rzeszow was a private city owned by the Lubomirsky family, whose stately summer palace and imposing castle attract a steady stream of tourists from all over the country.

Rzeszow’s Jewish population climbed incrementally, from 1,200 in 1765 and 7,000 in 1900 to 11,000 in 1931. It was not until the end of the 19th century that Jews enjoyed equal civic rights.

With the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918, Rzeszow was thrown into a brief period of upheaval and anarchy that affected Jews adversely. A pogrom broke out on May 3, 1919, resulting in the deaths of nine Jews.

During the interwar period, when antisemitism was on the rise in Poland, Zionist fervour impelled Jews to immigrate to Palestine.

Today, a visitor finds few visible reminders of the Jewish past in Rzeszow, a center of the Polish aircraft industry which has a population of around 200,000 and which was visited by the Polish pope, John Paul 11, in 1991 during a triumphal trip to his homeland.

The Old Synagogue, rebuilt after the war, is within easy walking distance of Market Square, which is dominated by a statue of Polish revolutionary Tadeusz Kosciuszko and filled with an assortment of hip shops, cafes and restaurants.

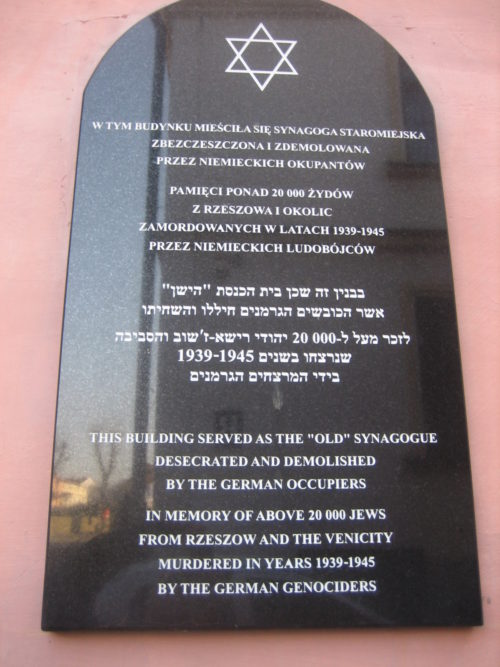

A plaque on the wall of the non-descript shul pays homage to the Jews of Rzeszow and environs who were killed by German “genociders.” Until recently, the building was used as a municipal archive. According to Mazurek, it will be returned to Poland’s Jewish community.

A low stone monument, in a compact park across the street from the Old Synagogue, informs visitors who can read Polish that this was the site of Rzeszow’s Jewish cemetery. The Nazis dismantled it and cut the tombstones into paving stones.

Around the corner stands the drab-looking New Synagogue, which has been converted into an art gallery and office building. The Nazis turned it into a stable, but as the Red Army approached in 1944, they set fire to the synagogue.

A glass case on the ground floor, containing a modest collection of fading black and white photographs of pre-war Jews, reminds a visitor of Rzeszow’s bygone Jewish dimension.

As I continued walking around Rzeszow, I came upon a street sign in the vicinity of Market Square named in honor of a famous Jewish patriot, Berek Joselewicz (1764-1809), who participated in the Polish uprising against the Austrians.

Mazurek told me that Joselewicz street signs are found everywhere in Poland.

As my tour ended, he took me to Rzeszow’s cultural center, the construction of which was funded by a local Jewish philanthropist in the 1920s. Inside its main hall was an exhibit on Poles who had rendered assistance to Jews during the Holocaust.

As I gazed at the somber faces of the Polish men and women who had risked their lives to help Jews, I felt I owed them a great deal of gratitude. But their humanitarian efforts, however herculean, only scratched the surface.

The Nazis succeeded in wiping out Rzeszow’s venerable Jewish community, which, I imagine, will not be resurrected.