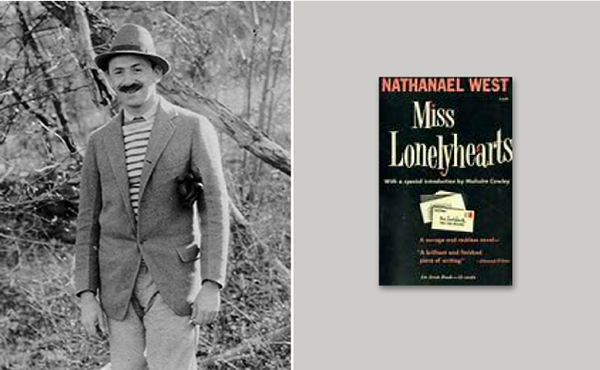

Nathanael West (1903-1940) was a promising but under-appreciated novelist during his brief lifetime. His four novels – The Dream Life of Balso Snell (1931), Miss Lonelyhearts (1933), A Cool Million (1934) and The Day of the Locust (1939) – sold fewer than 5,000 copies, garnered mixed reviews and earned a pittance.

Tragically, he did not live long enough to revel in the critical acclaim and fame that would inextricably be associated with his name years after his death.

It surely would have gladdened his heart had he known that two of his works, Miss Lonelyhearts and The Day of the Locust, dark, surreal and satirical, would be considered classics.

“Nathanael West was one of the great builders in American literature … but he did not know it,” writes his latest biographer, Joe Woodward, in Alive Inside the Wreck (OR Books). “His reputation was fixed almost completely postmortem, and it grows today …”

Interest in West – whose name at birth was Nathan Weinstein – and in his canon remained limited until 1946, when his masterpiece, Miss Lonelyhearts, was reprinted in France and then in the United States, Woodward notes. A reprint of The Day of the Locust, in 1950, added to his lustre. But according to Woodward, West’s reincarnation really flowered with the publication of The Complete Works of Nathanael West in 1957.

Apart from his novels, he co-wrote two plays, one of which was produced and poorly received, and a smattering of largely unpublished short stories. He was also a scriptwriter in Hollywood, banging out screenplays for 13 “B” westerns and gangster movies. West had a love/hate relationship with Tinseltown, but his activity as a screenwriter kept destitution at bay and enabled him to gather the material for The Day of the Locust, which has been compared to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Last Tycoon, a biting satire of the American movie industry.

West was born in New York City’s sedate, well-to-do Upper East Side. His parents, Max and Anna, immigrated to the United States from Lithuania in the late 19th century. The family was prosperous, having gone into construction.

West, though a voracious reader, was a mediocre student. Incredibly enough, he was admitted into Tufts College by doctoring his high school transcript. With failing grades in every subject, he left before he could be expelled. But within a year, he gained admission into Brown University by hijacking the transcript of another Tufts student named Nathan Weinstein.

At Brown, an Ivy League institution, West applied himself, immersing himself in the literary classics of Tolstoy, Flaubert, Conrad and Kafka and writing his first published works, a poem, a satire and a spoken spoof. Woodward argues that Brown provided West with “a foundation from which he matured as a professional writer.”

In 1926, he anglicized his name. West’s brother-in-law, the humourist S.J. Perelman, claims he was not ashamed of his surname: “He wanted a short and recognizable name.” The explanation does not wash. Was Nathan Weinstein not “short” enough? In an era of endemic and casual antisemitism, some Jews tried to mask their identity by tinkering with their name.

After graduating from Brown, West worked for his father as a building superintendent. Shortly afterward, he went to Paris, which had attracted such Americans as Ernest Hemingway and Ezra Pound. West hoped to spend at least a year in France and Europe, but, unable to earn any money, he returned to New York City within three months.

West’s pragmatic mother, considering writing a hobby rather than a profession, found her son his first real job as an assistant night manager at a family-owned hotel in Manhattan, Kenmore Hall. There, he began writing The Dream Life of Balso Snell. On the strength of a promotion, he became the manager of the Sutton Hotel.

His position at the Sutton gave him what he desired – solitude and companionship, an opportunity to release his creative juices and a chance to cultivate friendships with such up-and-coming writers as Edmund Wilson, Erskine Caldwell, Lillian Hellman and Dashiell Hammett.

Although West was a pessimistic person, his personality formed on the anvil of the Depression, he was outwardly amiable and possessed a gift for making friends.

West’s first novel, The Dream Life of Balso Snell, was less than a commercial or critical success, but it established him as a published novelist.

He fared better with Miss Lonelyhearts, but just as the positive reviews began pouring in, the publisher went bankrupt. West’s cousin, a lawyer, purchased the copyright for $1, and another company published the novel. But by then, it had been virtually forgotten, and the new edition was remaindered.

Much to West’s fortune, Twentieth Century Pictures bought the movie rights, while Columbia Pictures offered him a contract as a scriptwriter. The job did not last long, but West would return to Hollywood.

A Cool Million was rejected by West’s publisher, but found a new home in another publishing house. The reviews were lukewarm and within a year it was remaindered. Columbia Pictures, however, purchased the film rights.

West, having failed to sell a play to Broadway, returned to Hollywood in 1936 as a screenplay writer for Republic Pictures. He was drawn to the salary, the writers and actors and southern California’s mild weather, but was repelled by the cutthroat studio culture.

He left Hollywood in 1938, on the eve of the publication of The Day of the Locust, which generated poor sales. Indeed, as Woodward observes, his profits from the book was equivalent to one month’s pay in Hollywood. In 1940, he went back to Hollywood yet again.

West was happiest in the last year of his life. He was newly married, having wed a Disney Studios secretary, Eileen McKenney. He was at work on a fifth novel. As an aficionado of hunting and fishing, he enjoyed the year-round access to the outdoors that California offered.

And he was constantly employed. He and his new writing partner, Boris Ingster, sold two film treatments for $35,000, or about $500,000 in today’s currency. “At this point in his Hollywood career, West was a real success,” Woodward says.

It all came to a crashing end in the California desert on Dec. 22, 1940. Returning from a holiday in Mexico, West, a notoriously bad driver, collided with a car as he crossed an intersection. He and his wife were killed. She was cremated, her ashes placed inside West’s coffin.

West endured rejection, apathy and poverty in his fleeting 37 years in this vale of tears. But he persevered, vaulting to a rarefied place in literature. Regrettably, he did not live to savour it.

In Alive Inside the Wreck, Woodward successfully charts the highs and the lows of West’s life.