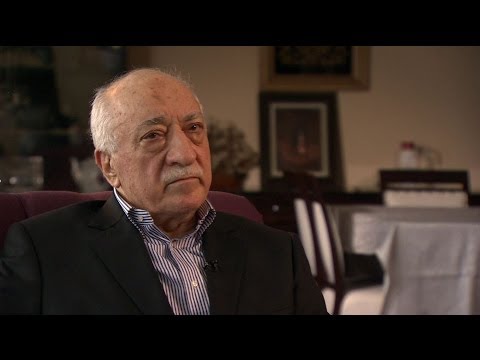

The reclusive Turkish cleric who heads Turkey’s influential Hizmet (Service) movement has become front-page news since the recent abortive coup in Turkey.

Fethullah Gulen, who lives in semi-seclusion in Saylorsburg, Pennsylvania, has been accused by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of masterminding the July 15 attempt to overthrow him. Erdogan called the failed military coup a “clear crime of treason” and intimated that the plotters should receive the death penalty.

He has now begun a massive purge. Nearly 18,000 people in all, including 6,000 military, almost 9,000 police, as many as 3,000 judges, 30 governors and one-third of all generals and admirals, have so far been removed from office because of suspicions that they have links to the Gulen movement.

He has also demanded that the United States allow for Gulen’s extradition, so he can be tried in Turkey.

Gulen has denied any involvement. “My message to the Turkish people is never to view any military intervention positively,” he stated, “because through military intervention, democracy cannot be achieved.”

The 75-year-old imam began preaching in the Aegean city of Izmir in the 1970s, and soon began urging his followers to “move in the arteries of the system, without anyone noticing your existence, until you reach all the power centers.”

In 2000 Turkey’s authorities, under the secular government of Bulent Ecevit, charged him with plotting to overthrow the government, but he had moved to United States two years earlier. A Turkish court acquitted the preacher of the charges in 2003, but he remained in the U.S.

The Gulen movement contends that it runs more than 2,000 educational premises, including charter schools, university departments, language centers and religious courses, in 160 countries.

It also controls billion-dollar business interests such as media companies, banks and construction firms.

Gulen has an estimated two million disciples and a further two million sympathizers at home and abroad. Hizmet followers in Turkey have until now continued to hold influential positions in institutions from the police and secret services to the judiciary.

As a fellow moderate Islamist, Gulen at first backed Erdogan’s Justice and Development (AK) Party, helping it to its electoral victories after 2002. But in 2013 the alliance began to come apart, as police investigations into government corruption were blamed by Erdogan on Gulan.

Mass arrests were carried out as part of an inquiry into alleged bribery involving public tenders. The sons of Interior Minister Muammer Guler, Economy Minister Zafer Caglayan and Environment Minister Erdogan Bayraktar were among those detained.

Infuriated, Erdogan closed down the network of private schools run by Hizmet and has been his bitter enemy ever since.

Erdogan has compared Gulen and his supporters to a virus and a medieval cult of assassins. An official from Erdogan’s ruling AKP called the Gulen movement a fifth column.

Gulen and Erdogan had an earlier confrontation in 2010 over the Israeli commando raid on the Mavi Marmara, one of six civilian ships of the “Gaza Freedom Flotilla” organized that May by the Free Gaza Movement, a coalition of pro-Palestinian groups, and the Istanbul-based Foundation for Human Rights and Freedoms and Humanitarian Relief (İHH).

They were trying to break Israel’s naval blockade of the Hamas-ruled Gaza Strip. Nine Turkish activists were killed during Israel’s commando raid.

While Erdogan angrily denounced the Israeli action, Gulen criticized the organizers’ failure to reach an accommodation with Israel. “What I saw was not pretty, it was ugly,” he told the Wall Street Journal on June 4, 2010. Gulen described their conduct as “a sign of defying authority and will not lead to fruitful matters.”

American Jewish organizations have been somewhat wary of Gulen, particularly because of sermons and writings from the 1980s that Joshua Hendrick, a sociologist at Baltimore’s Loyola University, described as “highlighting Jews as a crafty, wily group of people who were successful because of being clever, but this is spoken with a tone of being something suspect.”

In a book he published in 1995, Gulen called Jews “very intelligent. This intelligent tribe has put forth many things throughout history in the name of science and thought. But these have always been offered in the form of poisoned honey and have been presented to the world as such.” He added that they had an “incurable enmity to Islam and Muslims.”

Supporters today, however, describe Gulen as a moderate Muslim cleric who champions interfaith tolerance and dialogue.

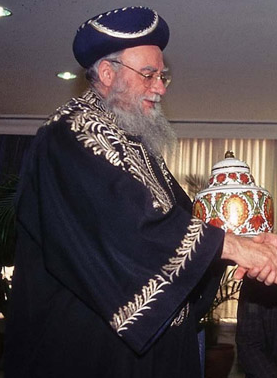

Gülen seems to have moderated his views towards Jews and Christians, and now condemns antisemitism. Among the outreach meetings Gulen can claim to have facilitated is one with Israel’s then-Sephardic chief rabbi, Eliyahu Bakshi-Doron, during Doron’s visit to Istanbul in 1998.

In an interview with the Atlantic magazine in August 2013, Gulen said, “I had a chance to get to know practitioners of non-Muslim faiths better, and I felt a need to revise my expressions from earlier periods.”

He added, “I sincerely admit that I might have misunderstood some verses and prophetic sayings. I realized and then stated that the critiques and condemnations that are found in the Quran or prophetic tradition are not targeted against people who belong to a religious group, but can be found in any person.”

He told journalist Jamie Tarabay, “I have not done anything that I did not believe to be in the footsteps of the Prophet Mohammed. He was the one who stood for a funeral procession of a Jewish resident of Medina, showing respect for a deceased fellow human being.

“It is a fact that I criticized certain actions of Israel in the past. But in my mosque sermons, I also categorically condemn terrorism and suicide bombings that target innocent civilians.”

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.