Weimar, a pleasant city in the eastern state of Thuringia, is where the tangled and irreconcilable strands of Germany’s history meet abruptly.

Although Weimar was the birthplace of the short-lived Weimar Republic, Thuringia was a bastion of the Nazi movement, having been the first state in Germany where two Nazi officials, Wilhelm Frick and Fritz Sauckel, achieved ministerial power in 1930 and 1932 respectively.

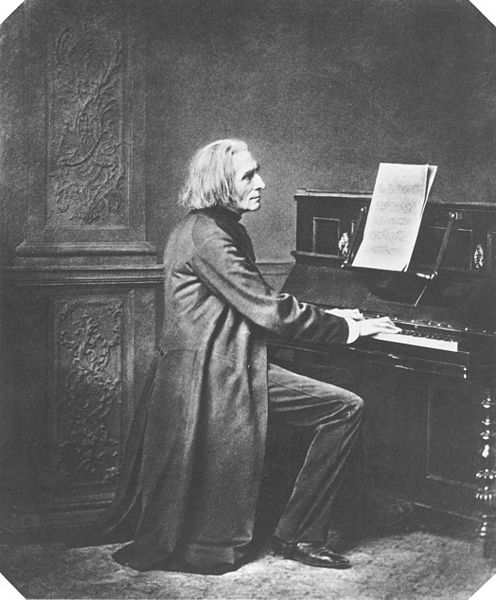

Despite its 20th century association with fascism, Weimar was a major center of high German culture, having nourished literary figures such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller and composers like Johann Sebastian Bach and Franz Liszt. Their homes have been converted into museums.

The 16th century painter, Lucas Cranach the Elder, lived in Weimar, too. His half-timbered, fairy tale house rounds off an exquisite ensemble of renovated Renaissance buildings in Weimar’s central square, known as the Marktplatz.

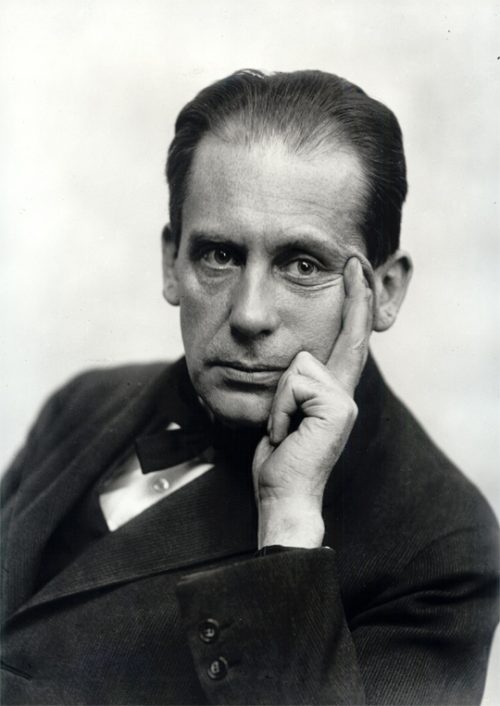

The Bauhaus architecture movement, founded by Walter Gropius in 1919, the year the ill-fated Weimar Republic was proclaimed in the National Theater, is rooted in Weimar.

The statues of Schiller and Goethe stand resolutely in front of the dull grey building where post-World War I German democracy was born, only to be snuffed out by Adolf Hitler little more than a decade later.

Under Frick’s and Sauckel’s baneful influence, Weimar became a center of Nazi racial research and antisemitic agitation. Hitler, who rose to power in 1933, visited often and stayed at the Hotel Elephant, which is still regarded as one of the finest hotels in the region.

In the wake of Kristallnacht, the nation-wide pogrom which served as a prelude to the Holocaust, Jewish residents of Weimar were interned in the Buchenwald concentration camp, only eight kilometers away.

Jewish detainees were released after promising to leave Germany. Jews unable or unwilling to emigrate were dispatched to the Auschwitz and Treblinka extermination camps in 1942, sharing the fate of Jews from neighboring towns such as Gotha, Jena and Eisenberg.

With the fall of the Third Reich, a handful of Holocaust survivors returned to Weimar, thereby invalidating the Nazis’ grandiose vision of a Judenrein city. Weimar, with a population of 65,000, is today home to a modest Jewish community, many of whose members are originally from the now-defunct Soviet Union.

Buchenwald was opened in the 1930s as a camp for political dissidents, religious dissenters, social misfits, homosexuals, common criminals and, of course, Jews. During World War II, Allied soldiers, including Soviets and Canadians, were incarcerated in Buchenwald.

The camp was converted into an anti-fascist museum cum-memorial by communist East Germany, which fell apart in 1990 and was amalgamated into West Germany to form a unified country.

Buchenwald sprawls over some four square kilometers, running into thickly forested valleys where prisoners’ huts once stood. From the green Ettersberg hills, 470 meters above sea level, the outlines of Weimar are visible.

Guarded by the SS, Buchenwald was a work camp, funnelling inmates from more than 50 countries into armament factories on the grounds and in Weimar.

Buchenwald had no gas chambers, but crematoriums, manufactured in nearby Erfurt by Topf & Sohne, were installed in 1940 to dispose of prisoners who had been shot or who had succumbed to gruesome medical experiments and disease.

It’s estimated that 55,000 inmates, of whom 11,000 were Jews, perished in Buchenwald.

Liberated by the U.S. army, it fell into Soviet hands after the division of Germany and was used as a labor camp for Nazis and political prisoners.

The passage of time has wrought changes in Buchenwald. Virtually all its buildings, from the barracks to the munition plants, are long gone. The factories were bombed by Allied aircraft in 1944, while the barracks were dismantled in the 1950s to cope with a scarcity of residential housing.

The crematoriums, however, remain intact, a chilling reminder of the depths to which Germany sank under Nazism.