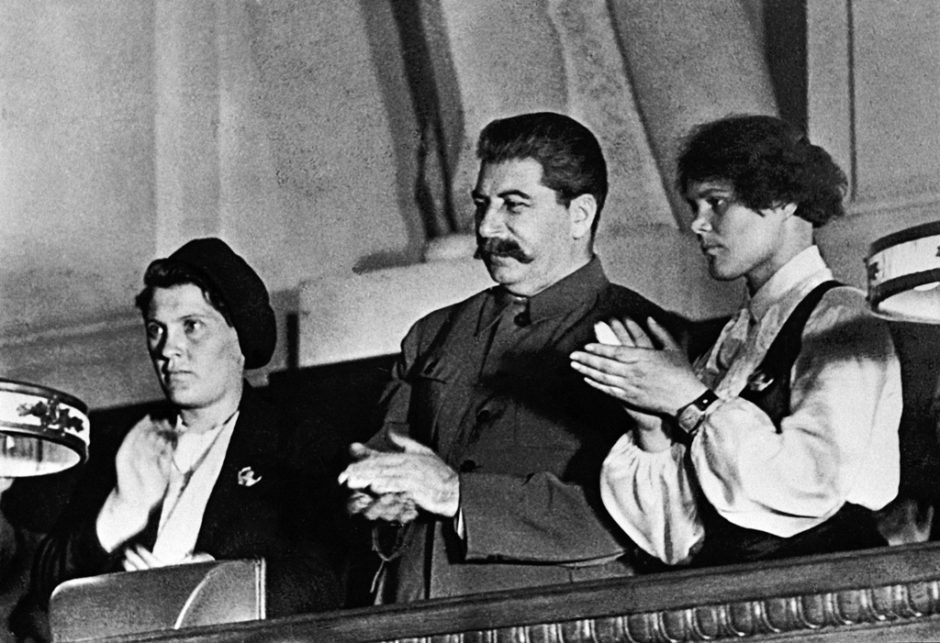

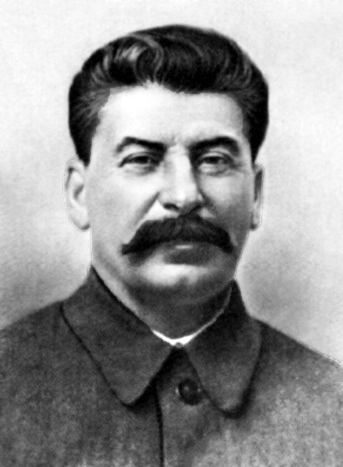

On Sunday, March 1, 1953, Joseph Stalin’s longtime maid, Matryona Petrovna, found him lying on the floor in his library. He was unconscious and his night clothes were drenched in urine. The supreme leader of the Soviet Union had suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and was at death’s door.

Petrovna quickly alerted his guards, who promptly notified their superiors. The news of Stalin’s collapse was solemnly announced on Radio Moscow on March 4 after members of his inner circle — Georgy Malenkov, Lavrenti Beria, Nikolai Bulganin and Nikita Khrushchev — had agreed on how to share Communist Party and central government authority.

A day later, Stalin, one of the tyrants of the 20th century, died.

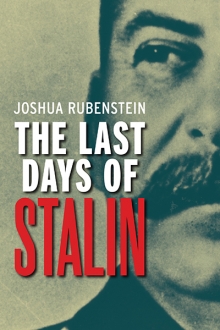

Stalin’s death set off a chain reaction of events that are recounted lucidly and meticulously by Joshua Rubenstein in his splendid book, The Last Days of Stalin, published by Yale University Press.

Rubenstein, an associate of the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies at Harvard University and an expert on the now-defunct Soviet Union, sheds light on a panoply of events — Stalin’s campaign against the Jewish community during his final years in office, the struggle for power that ensued following his stroke, the Cold War tensions that flared on the day he died, the reforms his successors introduced after his demise, and the manner in which the United States, the Soviet Union’s rival, responded to some of these developments.

As Rubenstein points out, Stalin had been in poor health since at least 1945, when he started taking off more time for rest cures in the Caucasus. A foreign diplomat who saw him in 1947 said he looked like a “very tired old man.” His personal physician, in 1952, urged him to consider retirement.

A doctor who treated Stalin during this period offers the starkest appraisal of his deteriorating medical condition. As a result of the progressive hardening of Stalin’s arteries in his brain, his judgment had become impaired. “In essence, a sick man ruled the state,” he observed.

Seven months before Stalin collapsed in his Moscow apartment, he told colleagues he intended to replace the ruling Politburo with an expanded Presidium, tighten control over collective farms and improve housing conditions and salaries for workers.

Paranoid as usual, he accused his closest associate, Vyacheslav Molotov, of behaving timidly in the face of American imperialism, and directed equally scathing criticism at two other figures in his circle, Anastas Mikoyan and Kliment Voroshilov. Strangely enough, Lazar Kaganovich, the last remaining Jew in the nine-man Politburo, was spared Stalin’s wrath.

By then, Stalin had already launched a barrage of attacks against Soviet Jews. The enormous Jewish crowds that enthusiastically welcomed Israel’s first ambassador to Moscow, Golda Myerson, raised questions in Stalin’s suspicious mind about the loyalty of Jews to the motherland. Blaming the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee for whipping up pro-Israel sentiment, he banned it, condemning it as a “center of anti-Soviet propaganda.”

This was a bizarre accusation, since the committee had been formed, at Stalin’s behest in 1941, to encourage support in the West for his alliance with capitalist countries like the United States and Britain.

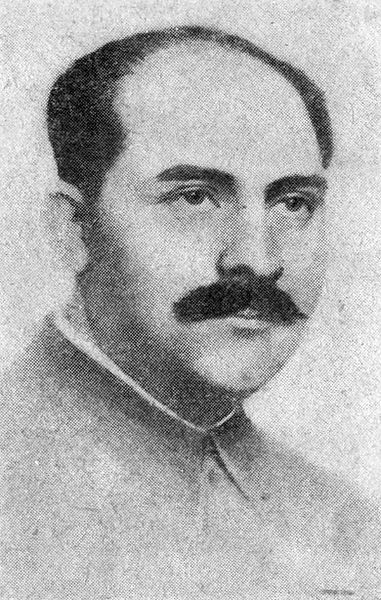

Not content with dismantling the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, the Soviet government arrested, tortured and executed 13 of its leading members on August 12, 1952. Among the victims were the Yiddish poets and writers Peretz Markish and David Bergelson.

As Rubenstein suggests, this was a crime representing merely the tip of a menacing iceberg. Within the framework of its anti-Western and anti-cosmopolitan campaign, the Soviet Union closed Yiddish-language periodicals and publishing houses as well as Yiddish theaters and removed Jews from senior government positions. And in the infamous Doctors’ plot, Stalin accused widely respected Jewish doctors of plotting to murder Kremlin leaders.

At Stalin’s insistence, the anti-Jewish campaign was extended to Soviet satellite states such as Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Romania.

Amid this poisonous atmosphere, rumors suggested that Stalin intended to deport Soviet Jews to Kazakhstan, Siberia or, perhaps, the Jewish autonomous region in Birobidjan. Aleksandr Yakovlev, a principal adviser to Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader, believes that preparations for the mass deportation of Jews were well under way in the winter of 1953. Rubenstein dismisses these rumors, saying that not “a single document has been located that can confirm that such a plan was ever considered.”

Israel, though concerned by the witch hunt targeting Jews, was loathe to break diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union. But after Israeli right-wingers damaged the Soviet legation in Tel Aviv, setting off an incendiary device that injured the wife of the ambassador and blew out windows, Moscow broke ties with Israel despite Israeli Prime Minister David Ben Gurion’s denunciation of the crime.

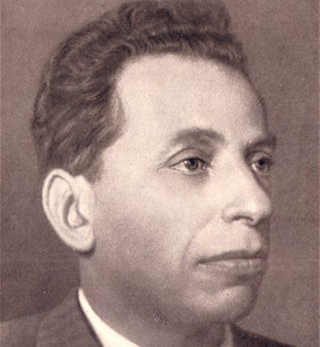

Rubenstein claims that Stalin’s passing did not diminish the ferocity of the anti-Jewish campaign. Just a day after his death, Solomon Mikhoels’ Order of Lenin was withdrawn by a secret decree. Mikhoels, murdered by the KGB in 1948 and denounced in 1953, had been one of the most prominent Jewish actors and theater directors in the Soviet Union.

In the wake of Stalin’s state funeral, Mikhoels was rehabilitated, the Doctor’s plot was disavowed and the Jewish physicians who had been arrested were released from prison. But the Kremlin offered no explanation as to why the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee had been disbanded. Nor did it offer a full accounting of the antisemitic campaign. Almost three years would elapse before Khrushchev delivered his famous speech denouncing Stalin’s crimes.

Cold War tensions escalated after the funeral. Two Czech aircraft were shot down by a U.S. fighter jet over West Germany, and shortly after this incident, a Soviet airplane brought down an unarmed British bomber over German territory.

Within five days of Stalin’s death, the Soviet Union offered the West an olive branch, calling for “prolonged coexistence and peaceful competition.” In response, the president of the United States, Dwight Eisenhower, refrained from offering substantial concessions to the Soviets. According to Rubenstein, Washington regarded Moscow’s overture as “a stratagem to undermine Western resolve” over a range of burning issues.

Within the Soviet Union, the new leaders instituted a number of reforms, two of which were the release of more than one million prisoners from the Gulags and significant price reductions for food and consumer goods. “But the Kremlin remained intolerant of ‘bourgeois liberties’ and enforced its ideological presumptions with arrests, prisons, labor camps, psychiatric hospitals, internal exile, even deportation abroad, writes Rubenstein. “There would be no tolerance for any challenge to one-party rule.”

In effect, post-Stalin Soviet leaders condemned Stalin’s worst crimes, but preserved the structures of his dictatorship.