When I was five or six years old, my mother — an immigrant from postwar Poland whose appreciation of nature seemed boundless — introduced me to the glories of Montreal’s great urban forest, Mount Royal Park, which is still the most dominant landmark in a city filled with stately landmarks.

My love affair with this exquisite park, one of North America’s finest, remains undimmed to this day. It’s a gift my mother kindly bestowed on me.

Back then, we lived on St. Urbain Street, which was only two blocks away from the park. An artery running through the storied Mile End district, the heart of Jewish Montreal, St. Urbain Street was within easy walking distance of the No. 11 streetcar, which brought local residents to the top of “the mountain.”

On a bright summer morning, when the wild flowers in city gardens were already in full bloom, we boarded the street car at the corner of Park Avenue (as it was called before Quebec’s Quiet Revolution) and Mount Royal Avenue, where a mammoth Kik Cola sign adorned the roof of a non-descript building for as long as I can remember. As the streetcar chugged up the steep, thickly-wooded slope, I gazed out the window, totally smitten by the alluring sylvan landscape.

I was just a kid, but I instinctively knew that I was in my element. As far as I was concerned, the combination of old-growth trees, dappled light and clear blue skies was irresistible. My mother, a young and vibrant woman of 36, could tell I had been transported into a state of bliss. That blessed day has been imprinted in my memory since then. In retrospect, it was one of those rare moments that shaped my deep and abiding attachment to the outdoors.

Regrettably, I never again had the pleasure of riding the No. 11 streetcar. By the 1960s, it was long gone, a relic of the past, having been replaced by a winding road that cuts through Mount Royal Park. But its absence has hardly deterred me from regularly visiting the park, my single favorite destination in Montreal.

The road that supplanted the No. 11 is named after Camillien Houde, the former mayor of Montreal and a French Canadian nationalist who was interned during World War II because of his opposition to conscription, a hotly contested issue in Quebec in the early 1940s. Ironically, Houde opposed the building of a paved road through the park, the city’s largest green space and the site of an extinct volcano.

Love it or hate it, the road offers motorists scenic glimpses of western Montreal and affords intrepid cyclists the opportunity of barrelling down its precipitous slopes at speeds that might seem excessive. But whether you’re moving along on four wheels or two wheels, you should definitely pull into the lookout on the side of the road and contemplate the vistas in the distance: Jeanne-Mance Park (where my parents, my sister and I enjoyed occasional Sunday picnics), parts of Mile End and the Jacques Cartier bridge spanning the mighty St. Lawrence River.

Cartier, a French explorer, sailed down that river in the 16th century and became the first European to scale Mount Royal, which was inhabited by indigenous people. From the 19th century onward, real estate developers encroached on Mount Royal, carving out neighborhoods in the Cote-des-Neiges, Outremont and Westmount districts. Mount Royal was also whittled down to size by the addition of two huge cemeteries, which comprise about two-thirds of its current land mass.

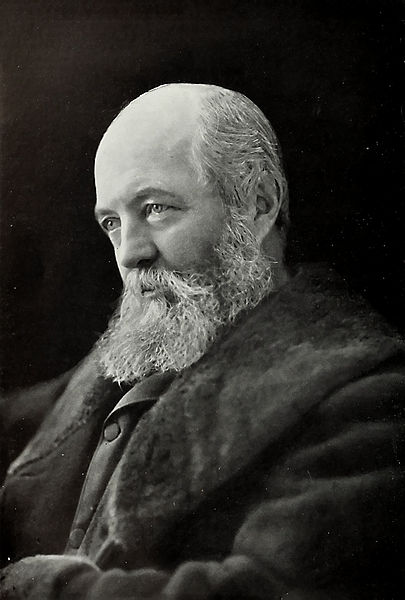

Mount Royal Park, the brainchild of Frederick Law Olmsted, a New York City landscape architect, was officially opened in 1876. During the course of his career, Olmsted designed several spectacular parks in the United States, including New York’s Central Park, which is equally magical, yet practical, in design.

Unlike Central Park, Mount Royal Park celebrates a major religion, Roman Catholicism. The 31-metre-high cross that crowns one of its summits was commissioned by the Saint Jean Baptiste Society, a French Canadian nationalist organization, in 1924. This occurred nearly 300 years after the French explorer Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve planted the first cross on its soil.

When I was a boy, I approached Mount Royal Park through Jeanne-Mance Park, which is much smaller, and Park Avenue, which always hummed with traffic. In those days, you crossed Park Avenue via a tunnel which always reeked of urine. To no one’s regret, it was demolished years ago. Today, traffic lights enable pedestrians to cross Park Avenue to Mount Royal Park with ease.

The approaches to the park are guarded by an imposing monument of a father of Canadian confederation, George-Etienne Cartier. In good weather, young people in the hundreds lounge on the meadow around the monument. A nearby gazebo, which I vividly remember from my childhood, was named in honor of Mordecai Richler, the famous Montreal-born novelist who died in 2000.

The heavily-wooded interior of the park is bisected by quiet trails and serene secondary paths which lead to utterly solitary cul de sacs. In places, the vegetation is so thick and lush that it resembles a dim primeval forest of the kind portrayed by the Grimm brothers in their sometimes menacing fairy tales. If you were led blind-folded into one of these hidden crevices, you’d never know you were in the middle of a big city.

On a recent trip to Montreal, I renewed my nostalgic boyhood bond with Mount Royal Park. Having checked into a hotel at Sherbrooke and Peel, near the bucolic campus of McGill University, I embarked on a short walk. Looking westward, I saw the wooded crest of the mountain. In this elegant neighborhood of chic shops, first-class art galleries, fine restaurants, expensive hotels and luxury condos, Mount Royal is omnipresent. It can’t be missed.

As I walked up Peel Street, my older daughter’s dog Rainbow harnessed to a leash, I passed old limestone mansions that had been converted into McGill faculty buildings. At Peel and Pine, I entered the outer perimeter of the park. After climbing a series of wooden staircases on a humid afternoon, I found myself in an unspoiled wilderness, literally minutes away from the noise and congestion of Montreal.

I climbed hundreds of additional steps before reaching the summit of Mount Royal, which, at 233 metres, forms the highest point on the mountain.

The plaza there, invariably buzzing with visitors, is dominated by a chalet, a stone-clad building whose walls are adorned with paintings of scenes from Canadian history. The lookout offers stunning views of downtown Montreal and environs.

As I strolled along Chemin Olmsted, I reached Maison Smith, a European-style cottage which hosts a permanent exhibit on the park. Beaver Lake, the artificial lake which serves as a skating rink during the long winter months, is just ahead. When I was a teenager, I spent many pleasurable hours tobogganing down the gentle snow-clad hills leading to Beaver Lake.

On another day, with Rainbow in tow yet again, I started my ascent to the chalet from L’Esplanade Avenue, which faces Jeanne-Mance Park and lies a block away from St. Urbain. Stretching languidly along the entire length of the park, and dotted with stolid buildings featuring grand staircases, tree-lined L’Esplanade brings back a flood of sepia-colored memories.

When I was a child, my parents and I would walk along L’Esplanade, pausing to catch up on gossip with neighbors from the old country. Occasionally, we’d sit on a bench, watching passing strollers. And it was here, on a shady path with an unobstructed view of Mount Royal, that I learned to ride a bicycle under my father’s patient tutelage.

On my most recent visit, I passed a familiar sight, the two-storey red-brick utilitarian building that is still the headquarters of the Canadian Grenadier Guards. Finished in 1913 and rededicated in 2012, it’s situated at the corner of L’Esplanade and Rachel Street, a few blocks from St. Laurent Boulevard, a fabled street which Mordecai Richler celebrated in his finely-wrought novels and essays.

Another building which caught my eye was a gated Italianate villa which was once served the Jewish immigrant community as a clinic. There, in 1951, my tonsils were removed.

For me, Mount Royal Park is more than a compelling place of singular beauty. It’s inextricably bound up with my youth and adolescence. It’s an integral part of my life.

It’s me.