Skepticism is the order of the day following an agreement between the United States and Russia to reduce the scale of violence in Syria’s five-year-old civil war and to coordinate American and Russian air attacks on Islamic State and other jihadist groups in Syria.

The complex accord, brokered in Geneva on September 9 by U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov after nearly a year of on-again, off-again negotiations, had no immediate positive effect on the ground. Fierce fighting continued, with Syrian government air strikes killing nearly 100 people in Aleppo, Idlib and the Damascus suburb of Douma.

The bloodshed was another sharp reminder that the Syrian conflict — which has claimed the lives of some 400,000 combatants and civilians, displaced millions of Syrians and left a tableau of destruction — will be extremely difficult to resolve.

A succession of international mediators have attempted to defuse the war, and last February’s “cessation of hostilities” pact, worked out by Kerry and Lavrov, collapsed in a heap of rubble. Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, Russia’s closest ally in the Arab world, used it as a cover to attack rebel-held eastern Aleppo and U.S.-supported insurgents.

The latest accord, which has been embraced by Iran and Hezbollah, two of Assad’s chief allies, was announced only four days after U.S. President Barack Obama and Russian President Vladimir Putin, failed to agree on its terms.

The pair, who have been sharply at odds over a variety of issues, met at a Group of 20 summit meeting in Hangzhou, China, in a bid to break the impasse. Acknowledging a lack of progress, Obama said that “gaps of trust” had not been closed. Only a month earlier, in Washington, Obama expressed similar doubts that a deal could be reached. “I’m not confident that we can trust the Russians or Vladimir Putin,” he said bluntly.

Obama’s hard-nosed attitude was echoed by U.S. Defence Secretary Ashton Carter, who pointedly questioned whether Russia really desires a durable truce in Syria. As he put it, “Unfortunately, so far, Russia, with its support for the Assad regime, has made the situation in Syria more dangerous, more prolonged and more violent.”

Despite Obama’s wariness, he instructed Kerry to press ahead with talks with Lavrov in the hope that a ceasefire in Syria, however limited and tenuous, might lay the foundations for a comprehensive political settlement down the road.

There are compelling reasons why the conflagration in Syria should be doused.

It has drawn tens of thousands of jihadists to Syria, turning that nation into an incubator for Islamic radicalism, one of the greatest threats of our time. The war has sporadically spilled over into northern Israel, raising the possibility that the Israeli armed forces might be sucked into it. The flow of about four million Syrian refugees into neighboring Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon has stretched their resources to the limit. Hundreds of thousands of Syrians have fled to Europe, creating the most serious refugee crisis since World War II and spawning anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim sentiment among Europeans.

If the most recent agreement to end the war is honored by both sides, talks about postwar arrangements in Syria may well begin. The biggest question, of course, is the fate of Assad, who has proven to be a tenacious survivor. Russia, though not necessarily wedded to him, is totally committed to the survival of his Baathist regime. So will Assad be a transitional figure, as the United States hopes? Or will he stay on as undisputed leader? All these questions will at the heart of future negotiations, should the Kerry-Lavrov agreement endure and should the rebels agree to negotiate with Assad.

If the accord holds, the United States and Russia are expected to establish a joint military command center to facilitate integrated operations against Islamic State and groups like Al Qaeda’s affiliate in Syria, Jabhat a-Nusra, a highly effective force which recently changed its name to Fatah Al-Sham.

A coordinated American and Russian air campaign would certainly be a step in the right direction. It would likely weaken Islamic State, which of late has suffered a series of military setbacks in Syria, Iraq and Libya. And it would probably further reduce the number of foreign fighters joining its ranks. By all accounts, the monthly flow of foreigners streaming into Syria from Turkey has been cut from a peak of 2,000 to 50 today.

Turkey, whose recent offensive into northern Syria deprived Islamic State of its last access to the Turkish border, appears ready to upgrade its contribution to the battle against Islamic State.

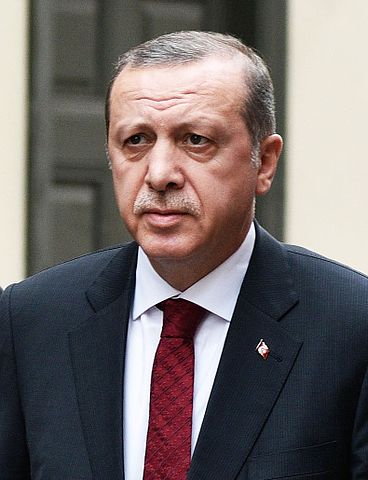

On September 7, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who recently quashed a military coup with ruthless efficiency and thereby consolidated his power, said that Turkey would be prepared to carry out joint operations with the United States to push Islamic State out of Raqqa, its de facto capital in eastern Syria.

Until now, the thrust of Turkey’s operations have been mainly aimed at Syrian Kurds, who are trying to establish a semi-autonomous enclave along its border with Syria.

Russia’s military intervention in Syria began last September, when Putin dispatched a squadron of Sukhoi fighter-bombers and Tupolev bombers to a base near the city of Latakia. This occurred after the Assad regime lost chunks of territory in northern Syria to the rebels. Since then, the Russians have largely concentrated their fire power on rebel groups aligned with the United States.

Russia has launched relatively few raids against Islamic State. But in mid-August, Russian aircraft based in Hamdan, in northwestern Iran, bombed Islamic State and Fatah Al-Sham targets in Syria. The presence of Russian planes in Iran was a stunning surprise, since no foreign power had been allowed to use Iranian military facilities in at least 70 years. Hamdan provided Russia with an immense operational advantage. But within 24 hours of the Russian disclosure that its jets had taken off from Hamdan, Iran abruptly terminated the arrangement, archly annoyed by Moscow’s odd decision to publicize the raids.

It was an embarrassing blow to Russian pride and prestige, but Russia’s access to the Latakia base means that Putin can continue playing an important role in protecting and strengthening Assad’s regime.

This will be all the more true should Russia and the United States, in accordance with their new agreement, join forces to pummel jihadists in Syria.