With a deafening blast from its foghorn, the R.M.S. Segwun, North America’s oldest operating steamship, set off from its base in Gravenhurst, Ontario, for a serene two-hour cruise of Muskoka Bay and the broader expanses of Lake Muskoka.

My wife and I were aboard as it left Gravenhurst’s historic Wharf district on a pleasant sunny day in mid-September.

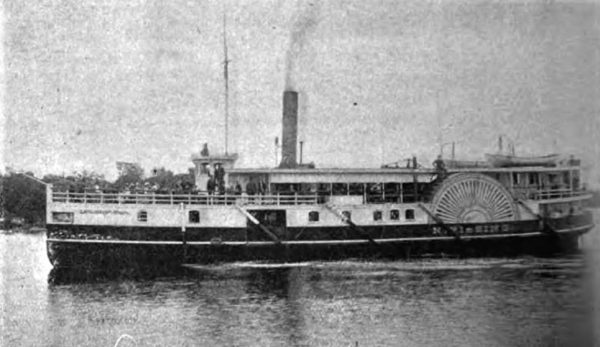

Originally named the SS Nipissing, the R.M.S. Segwun once transported passengers, freight and mail from Gravenhurst to a maze of cottages and resorts in the Muskoka Lakes district, colloquially known as “cottage country.”

As the sole survivor of a fleet of identical ships that plied these glistening waters during the golden age of the steamship from the 1860s to the 1950s, the R.M.S. Segwun is a floating museum of regional history.

Carrying a maximum of 99 passengers, it was constructed in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1887 and assembled as a side paddlewheel steamer in Gravenhurst, about 150 miles north of Toronto.

Refitted and relaunched in 1925 under its present name, it made its last trip in 1958 and was then decommissioned. Offered for sale as scrap, the town of Gravenhurst — the gateway to Muskoka — raised a hue and cry and bought it for a symbolic sum of $1 before converting it into a maritime museum.

Following further restoration, the R.M.S. Segwun was commissioned as a cruise ship in 1981. Its sister vessel, Wenonah II, was launched in 2002. Its predecessor, the Wenonah I, made its debut in the spring of 1866 as the very first steamship to ply the Muskoka Lakes.

The proprietor of the Wenonah, A.P. Cockburn, ran the Muskoka Navigation Company, which was instrumental in opening up tourism in Muskoka. A visionary, he convinced the Ontario government to build locks to connect Lake Muskoka with two adjacent lakes, Lake Rosseau and Lake Joseph, and thereby expanded the territorial scope of the tourist industry.

As a result of these developments, railway lines came to Muskoka, which became the hub of a booming timber trade and boat building empire. At one point, the Muskoka region was home to 11 boat builders, one of which assembled the R.M.S. Segwun, now the oldest operating hand-fired steamship in Canada or the United States.

As we boarded the R.M.S. Segwun, along with scores of fellow travellers, I had a gut feeling I was in store for a nice, relaxing and informative afternoon of sight-seeing in one of Canada’s most scenic corners.

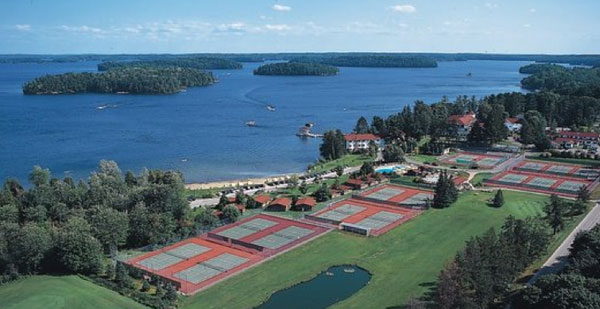

The guide on the vessel, a congenial man in his late 60s or early 70s, gave us a running commentary on Lake Muskoka, one of 1,600 bodies of water in the general vicinity. He told us the lake has a surface area of 115 square kilometers, is 26 kilometers long, 10 kilometres wide and is generally 15 meters deep.

The lake is dotted with 430 wooded islands. Brown Island is the largest one. Wilma Island, with a cottage occupying most of its territory, is among the smallest ones. Daisy Island is where the first resort in these parts was constructed. Eleanor Island, an islet, is the sole bird sanctuary on the lake. Designed to protect gulls and blue herons, it has been virtually taken over by cormorants.

The lake abounds with fish — principally rainbow trout, brown trout, walleye, northern pike, yellow perch and rock bass.

Cottages, equipped with boat houses, are nestled on the rugged cliffs of the Canadian Shield. The dense forests consist mainly of maple, birch, oak, spruce, hemlock and white and red pine. The wildlife ranges from beavers and otters to moose and mink.

A century ago, when lumberjacks worked these lands, the landscape, as well as the lake, looked completely different, the guide said.

There were few cottages to be seen and the forests had been largely denuded. Ten lumber mills, the last of which shut down in 1933, were strung out along the shore, turning out lumber and shingles. The lake was filled with logs destined for the mills. A man could supposedly cross the lake by jumping across the floating logs.

By then, tourism had become an intrinsic part of the local economy. And new paved roads facilitated the relatively short drive to Muskoka, once considered remote and isolated.

Roughly 100 rustic resorts, such as The Bluff and Riverdale House, catered to a well-heeled clientele seeking relief from the hurly-burly of city life. During this halcyon era, famous musicians like Duke Ellington, Glenn Miller and the Dorsey brothers entertained guests.

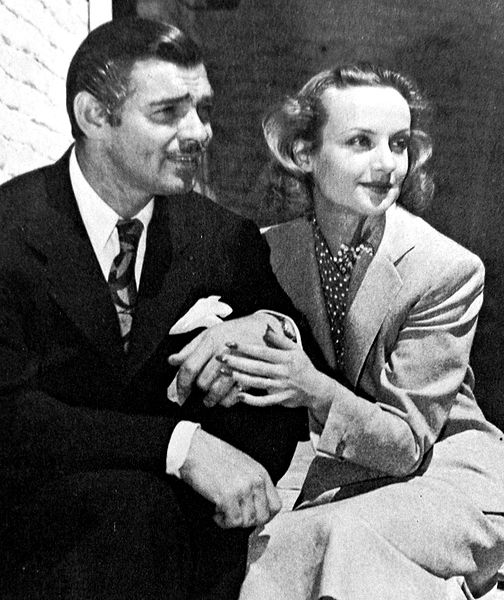

Such was Muskoka’s allure that the Hollywood movie stars Clark Gable and Carole Lombard honeymooned here.

Over the years, some resorts burned down. Still others closed due to changing times and tastes. As air travel became common and affordable, people opted for more exotic destinations far from Ontario. And as this process accelerated, steamship fleets dwindled.

Today, only ten of these grand resorts still exist, notably Clevelands House and Windermere House.

Strangely enough, Muskoka was also the home of a German prisoner-of-war camp in the 1940s. Situated on a hill near the Gravehurst Wharf, it was called Camp 20 and accommodated upwards of 490 German soldiers and officers. The story of the camp is recounted by Cecil Porter in The Gilded Cage: Gravenhurst’s Prisoner-of-War Camp 20, 1940-1946.

Ironically enough, the site was taken over by the Gateway Hotel, which would be Ontario’s largest Jewish resort in the 1950s. With its demise, a Jewish summer camp sprang up in its place.

Irving Ungerman, the late Toronto boxing promoter and a summer resident of Gravenhurst, bought the land and donated it to the town. Today, it’s known as the Ungerman Gateway Park.

Gravenhurst’s brief association with the POW camp goes unmentioned in the Muskoka Steamships and Discovery Center, which celebrates the region’s association with tourism, boat building and the lumber industry.

But who can be surprised by this omission?