I was surprised to read recently that China has cracked down on the minuscule Jewish community of Kaifeng. Historically, China has been a haven for Jews and one of the very few countries that has been free of antisemitism.

As part of President Xi Jinping’s campaign against unapproved religious faiths and foreign influence, the Chinese government has reportedly removed signs and relics of the city’s past from public places and shut down organizations instrumental in fostering Jewish consciousness.

This news brought back a flood of memories.

Some years ago, I was invited to China by the Chinese government to write about its Jewish dimension. China was interested in increasing tourism and hoped that a few newspaper stories about the Chinese descendants of Jews would elicit interest in Canada’s Jewish community.

A pleasant young woman from the government accompanied me around China. When we reached Kaifeng, 300 kilometers southwest of Beijing, we were received warmly by a representative from the municipality.

The next day, I was invited for a meal at a restaurant. I was joined at the table by six city officials who sang the praises of Kaifeng. As we partook of Chinese delicacies brought to the Lazy Susan by an army of waiters, they made no pretense about their interest in attracting Jewish tourists and investors from Canada.

Later that day, I met Moshe Zhang Xingwang, a short, squat, goateed man sporting a black embroidered yarmulke, green corduroy slacks, a blue and grey sweat top and black sneakers.

“Shalom,” he said as he greeted me in a high-pitched voice.

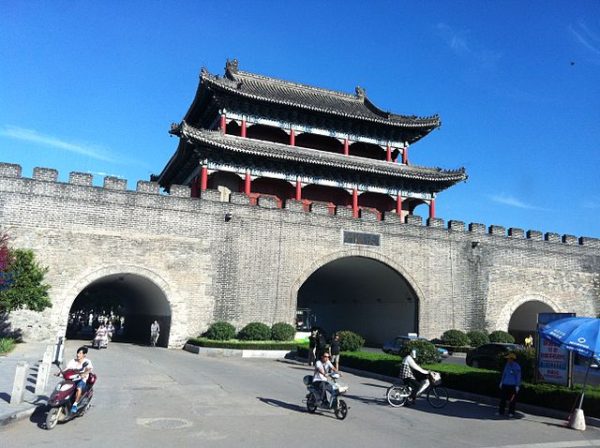

Moshe ushered me into the living room of his spare seventh-floor flat on the outskirts of Kaifeng, China’s former capital. As I had discovered the day before, Kaifeng is a clean and attractive city brimming with reconstructed imperial palaces and splendid monasteries and temples.

As I quickly looked around Moshe’s modestly-furnished apartment, I spied two brass menorahs resting on a shelf, a small plastic Israeli flag affixed to a wall and photographs of Moshe posing with Orna Namir (Israel’s former ambassador to China) and of the Western Wall in Jerusalem.

Moshe, a cheerful 56-year-old physical education teacher, was a direct descendant, on his father’s side, of Jews who had arrived in Kaifeng about 1,000 years ago. Whether self-appointed or not, he had set himself up as the spokesmen of his fellow Jews in Kaifeng.

By his estimation, there were roughly 1,000 Jews in China and several hundred in Kaifeng, where Jewish traders from Iran, India and Afghanistan had settled centuries ago. They reached Cathay, as China was then known, via the fabled Silk Road.

When I asked Moshe how he identifies himself, he said, “Chinese, with Jewish blood.” Munching an apple as he spoke, he explained that while he was an atheist, he felt a great kinship with his Jewish ancestors. He said he observes the sabbath, though not major Jewish holidays, lights candles on Shabbat and refrains from eating pork, a favorite Chinese meat. In deference to his forefathers, which he can trace back to the early 17th century, he wore a kipa.

Moshe started to seriously identify with his Jewish ancestors in the 1990s, when China launched significant economic reforms, modernized itself and began tolerating religious freedom.

In this spirit, he visited Nanjing University’s Judaic Institute to learn more about Jewish traditions and history and to ascertain how he could teach himself Hebrew.

Moshe told me that antisemitism had never intruded into his life. This was hardly surprising. Chinese emperors welcomed Jews, and the Jewish community in Kaifeng — the most permanent and durable one in China — was gradually so well integrated and assimilated into Chinese society that it simply disappeared.

Pan Guang, a Chinese scholar in Shanghai, claims that the first Jews came to China during the Han dynasty (206 BCE to 220 CE). But it was not until the 10th century, under the Northern Song dynasty, that Jews established a community in Kaifeng, then known as Dongjing.

Situated in the middle of Henan province, and lying along the shores of the Yellow River, Kaifeng was a thriving mercantile town.

The emperor, having accepted a tribute of cotton goods from the Jewish traders, supposedly declared, “You have come to our China. Respect and preserve your customs of your ancestors here in Kaifeng.”

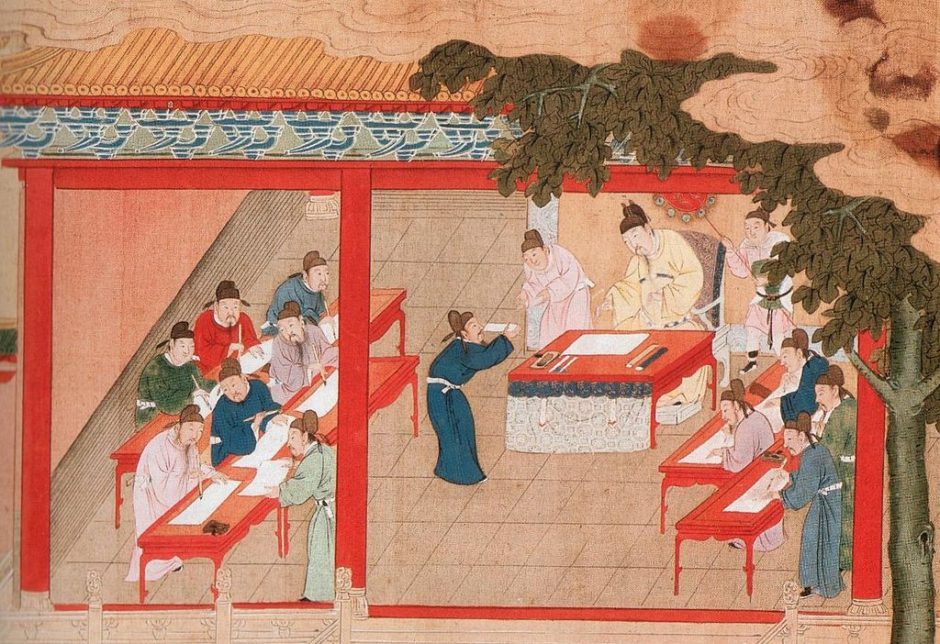

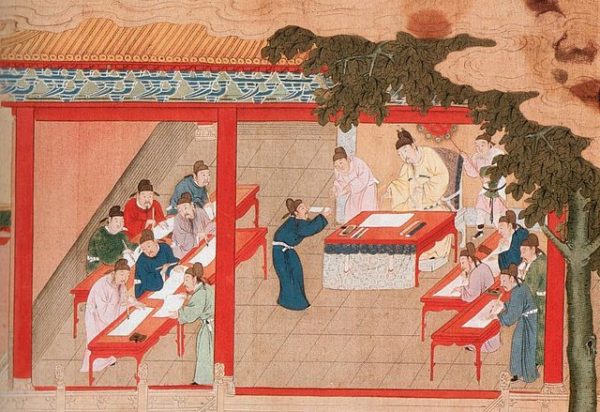

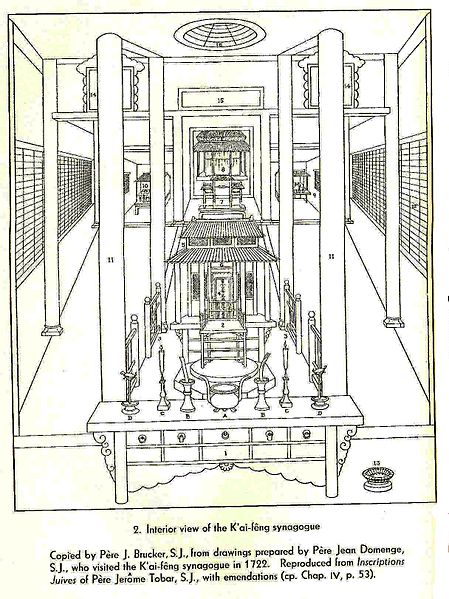

Enjoying equal rights and free to pursue their activities as merchants, the Jews of Kaifeng built a synagogue in 1163 and renovated it a century later. During the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), the community prospered, reaching a population of approximately 4,000 among 500 families.

Jewish communities also emerged in Guangzhou, Hangzhou and Ningbo, but only the one in Kaifeng endured for so long.

By the 17th century, Jews in Kaifeng had drifted into the civil service, the professions, the skilled crafts and agriculture. Amid a remarkable climate of tolerance and acceptance all but unique in the annals of Jewish history, they absorbed Chinese habits, dressed like Chinese, took Chinese names such as Zhao, Li, Ai, Gao, Jin and Shi and intermarried.

When the Ming emperors closed the Silk Road to commerce, the Jews of Kaifeng were isolated and forgotten. Their isolation was abruptly broken in 1605 when the Italian Jesuit priest, Matteo Ricci, met Ai Tian, a Chinese Jew from Kaifeng.

Less than 40 years later, the synagogue and many of its religious artifacts were swept away by a flood. In 1642, the shul was rebuilt in the shape of a pagoda.

Over the next few centuries, the community declined as Jews stopped practising Judaism and the last rabbi died. The synagogue fell into decrepitude and was inundated by flood waters once again.

During the 19th century, the deracinated descendants of Jews, some mired in poverty, sold Torah scrolls and Hebrew manuscripts to Christian missionaries. These priceless relics ended up in the British Museum, Oxford University, Cambridge University, Southern Methodist University in Dallas and the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati.

A small collection of artifacts, ranging from a lacquered wooden Torah case to rubbings from a stone stele commemorating the rebuilding of Kaifeng’s synagogue, found their way into the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto.

The Canadian connection is intriguing. Bishop William White, a Church of England missionary, tried to revitalize the community. In 1942, with the Holocaust raging in Europe, the University of Toronto Press published his book, Chinese Jews.

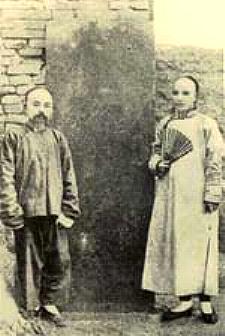

By 1907, when the National Geographic magazine published a piece by Oliver Bainbridge titled “The Chinese Jews,” the Jewish community of Kaifeng hardly existed. The community, he wrote, “has dwindled down to eight families, numbering in all about 50 persons, who have in great measure forgotten their characteristic observances through frequent vicissitudes and varied conditions of life.” Many of the Jews, he added, “had merged into Mohammednism …” And all efforts to bring them back to Judaism had failed.

During my visit to Kaifeng’s City Museum, the remnants of a dead community were displayed in “An Exhibition of the History and Culture of Ancient Kaifeng Jews.” The exhibit, displayed in two dusty, dimly illuminated rooms with barely legible explanatory signs and a geographically inaccurate map of the Silk Road, was normally closed to the public.

The curator also informed me that special arrangements had to be made to view the unimpressive objects, most of which were enclosed in a glass case: a large stone bowl, two stone tablets and three ink rubbings, all retrieved from the synagogue.

Five empty glass display cases had been left empty, waiting to be filled should more artifacts be found.

The ruins of Kaifeng’s synagogue disappeared after the land on which it had stood was sold to Canadian missionaries. The Number 4 Hospital now occupied the site. The hospital’s gloomy power plant was built on the site of the synagogue’s courtyard. (As per government instructions, the well near the synagogue was recently buried under concrete and soil).

Nearby was the Teaching Torah Lane, a narrow alley of drab cinder block homes which once housed the residential quarter of Kaifeng Jewry. There I met Cui Shin Ping, whose late husband, Zhao Pingyu, was a descendant of a Kaifeng Jewish family. Her home, consisting of two small rooms, was then something of a shrine to Kaifeng’s Jewish past.

On the walls, and arrayed on shelves, were photographs of long-deceased Kaifeng Jews in pigtails, paper cuts fashioned into menorahs, a Star of David, a decorative plate of Jerusalem and four brass menorahs.

These artifacts were the vestigial remains of a vanished Jewish community that had passed into oblivion through assimilation and near total isolation.