Masha Gessen does not mince words.

Birobidzhan, set aside by the Soviet Union in the late 1920s as a national homeland for Jews, was “perhaps the worst good idea ever.”

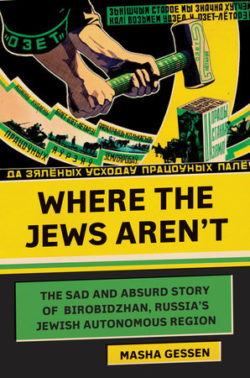

She develops this argument in an absorbing book, Where the Jews Aren’t: The Sad and Absurd Story of Birobidzhan, Russia’s Jewish Autonomous Region (Nextbook)

For a brief moment in the 1930s, Birobidzhan seemed like a going concern, a secular Yiddish outpost in the wilds of Siberia whose borders were defined by the Bira and Bidzhan rivers. But political purges, orchestrated by Joseph Stalin, and harsh conditions on the ground, doomed the project to irrelevance.

According to Gessen, a Soviet-born journalist who immigrated to the United States, the original idea behind Jewish settlement in Birobidzhan was formulated by the great historian Simon Dubnow. She empathizes with this form of “autonomism.” As she puts it, “It was his concept of a secular Judaism as the basis for national identity that … I recognized as the foundation of my own Jewishness.”

To Dubnow, a victim of the Holocaust, the Zionist notion of moving European Jews to Palestine was unrealistic. “Political Zionism is merely a renewed form of messianism” that “blurs the lines between reality and fantasy,” he noted.

Yet, as the enthusiasts of the ill-fated Birobidzhan scheme would learn to their bitter disillusionment, they were far less realistic than the Zionists, who ultimately attained statehood.

The titular head of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Kalinin, was apparently the first high-ranking communist official to raise the idea of a Jewish autonomous republic. He did so in 1926 in a speech to the Committee for the Settlement of Toiling Jews. What he actually had in mind was an agricultural colony modelled after Jewish colonies in Crimea and southern Ukraine that had been established in the first decade of Soviet rule.

In 1927, a team of agronomists was sent to the region, which was near the Chinese border. Their mandate was to ascertain whether it might be compatible with large-scale settlement. They produced an 80-page report which, she notes, read like “a list of arguments against the very idea.”

The terrain was inhospitable. The weather was inclement. The mosquitos and gadflies tormented men and beasts alike. The local population, consisting of Cossacks and ethnic Koreans, were none too eager to welcome an influx of Jews. Marauding gangs of Chinese thieves terrorized the area.

Moscow, having adopted a strategy of harnessing ethnic nationalism to preserve the multi-national Soviet empire, ignored the experts’ assessment. Indeed, the Soviet government expected Birobidzhan to attract a million settlers within a decade.

The first trainload of settlers arrived in the spring of 1928 only to find a wasteland. Apart from the dilapidated railway station, there was virtually nothing at the end of the line.

Two types of Jews went to Birobidzhan: Poor working-class Jews from Ukraine and western Belarus and Jews who had fled Russia in the early 20th century and had settled in the United States, Canada, Argentina and even Palestine.

“It is safe to assume that most of those who stayed either had no home at all to go back to or had no way of scraping together the cash for a return ticket,” Gessen writes.

The first settlers were directed to plots of land where they could start collective farms. It was not a successful endeavor. Only a handful had worked on a farm before, and heavy rains washed away their hard work.

One of the most important figures in Gessen’s book is the Yiddish poet and writer David Bergelson, who sang the praises of Birobidzhan. In 1932, he boarded the Trans-Siberian Railway to visit and was greeted as “a long-lost descendant of a royal Yiddish tribe.”

Three years later, he published an upbeat manifesto in which he described Birobidzhan as “one of the most important and prominent fronts in the establishment of a classless society.” He promised to help build “a glorious Jewish culture, socialist in form and national in content.” Shortly afterward, he announced his intention to live there. Gessen doesn’t believe he was ever serious. His announcement was strictly rhetorical, designed to whip up fervor for Birobidzhan.

Its high-water mark was in 1935 and 1936, when more than 8,000 settlers converged on Birobidzhan and one of Stalin’s closest associates and secretary of the Central Committee, Lazar Kaganovich, paid his first and only visit.

Kaganovich attended a gala performance of Sholem Aleichem’s play, The Gold Diggers, at the Yiddish theater and was treated to a traditional Jewish home-cooked meal. Before he left, he suggested that Birobidzhan should host a scholarly conference on the Yiddish language.

Famous last words.

During the late 1930s, waves of arrests swept through the autonomous republic, coinciding with the disappearance of Yiddish language activists in Moscow and Stalin’s crackdown on Jewish culture in the Soviet Union.

At this point in her book, Gessen segues to the formation of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee. It was created in 1942 to rally American moral and financial support for the Soviet Union following Nazi Germany’s 1941 invasion.

Bergelson was deeply involved in the committee’s activities. His herculean efforts did not save him from the post-war purge Stalin conducted against Soviet Jews and Jewish institutions. Arrested in 1948 on trumped-up charges of fomenting “bourgeois nationalism” and conspiring against the state, he was subjected to various forms of torture. He was executed on August 12, 1952, along with 12 other Jewish notables, in the Night of the Murdered Poets.

Prior to his execution, Birobidzhan’s leadership was purged from top to bottom and, shockingly enough, Yiddish-language books in the Sholem Aleichem Library were burned. A policy of Russification abolished Yiddish as the primary language of instruction in schools and erased Jewish references in institutions.

With the death of Stalin in 1953, jailed Yiddish writers were released, but for all intents and purposes, Birobidzhan was dead in the water. Harrison Salisbury, the New York Times‘ bureau chief in Moscow, visited in 1954 and wrote: “It was plain that Birobidzhan had lost its significance as a Jewish center a long time ago. I could not see that the place had any special Jewish character.”

In 2009, Gessen travelled to Birobidzhan, finding “a decent tourist infrastructure geared to the Jewish curiosity seeker.” Beyond that, she found an empty shell, a “falsification of history.”

Although one of its two main avenues is named after Sholem Aleichem, Birobidzhan is virtually bereft of Jews, the vast majority having immigrated to Israel from the late 1980s onward.

To use a modern expression, Birobidzhan was all smoke and mirrors, amounting to very little.