Although Christians have never represented more than about 11 percent of the Palestinian population in the Middle East, they’ve played a significant role in the Palestinians’ national movement.

Despite this fact, Arab Christians have been “largely overlooked in modern Palestinian history,” says Noah Haiduc-Dale in Arab Christians in British Mandate Palestine: Communalism and Nationalism, 1917-1948, published by Edinburgh University Press.

As he points out in this deeply researched and engaging book, Christians like Najib Nassar, George Antonius and Emil Habibi spearheaded the anti-Zionist movement in the first decades of the 20th century, both as political activists and publishers of Arab newspaper in Palestine.

And from the 1960s onward, Christians such as George Habash, Wadie Haddad, Nayif Hawatmeh, Kamal Nasser and Hanan Ashrawi occupied important positions as well.

In this volume, the author discusses the relationship between Arab Christians and the Palestinian national movement from Britain’s conquest and occupation of Palestine in 1917 to its withdrawal in 1948.

But before exploring this dimension, he writes about the Christian presence in the region. Until the Arab conquests of the 600s, the Middle East was almost wholly Christian. Subsequently, Muslims formed the vast majority of the populace.

By 1914, Christian Palestinians constituted just over 11 percent of Palestine’s population, with Greek Orthodox Christians being the biggest denomination (43 percent). They were followed by Latins (20 percent), Melkites (14 percent), Anglicans (5 percent) and Maronites (4 percent). The remainder were predominantly Syrian Orthodox, Coptics and Gregorians. There were also Armenians, but they did not consider themselves Arabs.

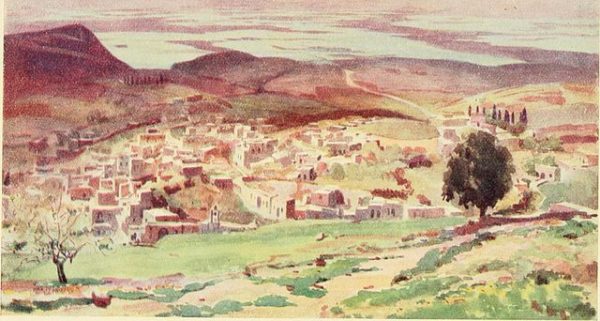

Most Christians lived in religiously mixed cities — Jerusalem, Jaffa and Haifa — but some were found in towns like Bethlehem, Nazareth, Beit Jalla and Ramallah, which had a mostly Christian population.

During the 400-year Ottoman period, which ended in 1917, minorities like Christians enjoyed substantial communal autonomy under the millet system. Some historians believe that Muslims and Christians lived as two separate groups, rather than as two parts of a single Palestinian community. Still other scholars claim that Christians had strong connections to Arab Muslims within the framework of their marginal and secondary position in Palestinian society.

Historians like Rashid Khalidi and Muhammed Muslih have advanced the argument that religious identification among Palestinians diminished in importance through the late Ottoman and Mandate epochs in favor of a secular national identification. But with the intensification of the conflict between Palestinians and Jews, and the increase in Islamic identification among some Arabs, Christians turned inward. Despite this shift, Haiduc-Dale says, Christians fully identified with the Palestinian cause.

Some of the earliest anti-Zionist propagandists were Palestinian Christians. Najib Nassar, the editor of the newspaper al-Karmil, was one of the first to warn of Zionist encroachments in Palestine. Founded in 1908, al-Karmil pressed for Arab unity and the establishment of an Arab political party to counter Zionist inroads.

According to Haiduc-Dale, Christians “participated in politics with their own interpretation of what was best for the nation, their specific denominational community and themselves.” He adds that Christians “were unified only in their opposition to Zionism.”

While openly supportive of the movement’s opposition to the 1917 Balfour Declaration and Jewish immigration and settlement, Christians were chary of the increased use of Islam as a tool of “nationalist rhetoric.” Haiduc-Dale agrees that Haj Amin al-Husseini, the mufti of Jerusalem, utilized “religious sentiments” to whip up support of the Palestinian cause among Muslims.

Christians responded to the outbreak of Arab-Jewish violence in Palestine in the 1920s in various ways. Some rejected it, while others endorsed it. But all Christians expressed support for the Palestinian agenda.

As for the 1936-1939 Arab Revolt, or uprising, the Christian level of participation in it varied. “Some Christians were deeply involved while others were not fully invested,” he says. Certainly, Christians played a leadership role in the labor movement and in perpetuating the general strike during the uprising.

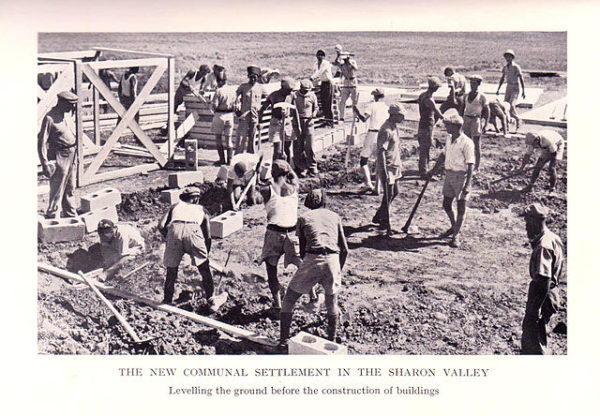

Haiduc-Dale points out that Christians were involved in the Arab communist movement, which opposed Zionism. Its organ, al-Ittihad, was founded in 1944 by a Christian from Haifa, Emil Toma. He, along with such figures as Tawfiq Tubi and Hanna Naqara, were among the movement’s most important leaders in the 1940s.

During the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948, Christian villagers were less likely to flee and more likely to be allowed to stay in their homes by the Israelis. Quoting the Israeli historian Benny Morris, Haiduc-Dale says that Christians usually did not resist Jewish forces and stayed in their homes, even if that meant submitting to Jewish rule. In Shefa’amr, for example, the Muslim majority fled, but the Christian and Druze inhabitants remained behind.

Christians continued to support the Palestinian national cause, even as many surrendered peacefully to the victorious Israeli army.

This “dual approach” was perhaps rooted in fear. But Haiduc-Dale offers another explanation: “A better assessment is that Christians were fully connected to both their national and religious labels and never abandoned one for the other.”