We should be beware of stereotypes, yet they persist from one generation to the next, twisting and distorting reality and causing misunderstandings and enmity.

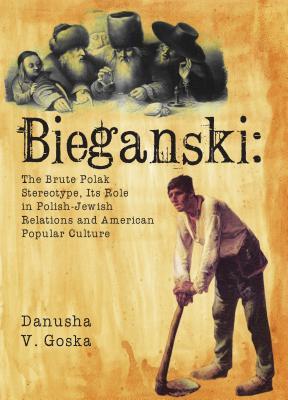

One of the oldest ones, concerning Poles, was perpetuated by William Styron in his novel Sophie’s Choice. Bieganski, a character in his book, is an antisemite. To some Polish Jews, especially Holocaust survivors outside Poland, a mythical Pole like Bieganski seems more real than imagined. In their minds, Poles are not only antisemitic but mentally dull and violent. Danusha Goska, an American scholar of Polish descent, examines this skewed perception of Poles in Bieganski: The Brute Polak Stereotype, Its Role in Polish-Jewish Relations and American Popular Culture, published by Academic Studies Press.

The topic she addresses in this wide-ranging book is of considerable interest because Jews and Poles have compiled a long record of coexistence in Poland. Until World War II, they usually lived in close proximity to each other, though not always in harmony. In short, Poles and Jews have had a mercurial relationship.

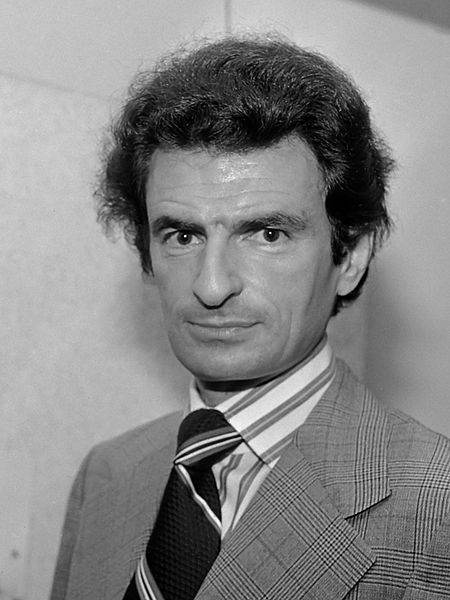

Jerzy Kosinki, the Polish-Jewish novelist, exploited the Bieganski stereotype in The Painted Bird, which was set in Nazi-occupied Poland and came off, as Goska suggests, as a Holocaust memoir of “bestial, violent, sexually perverse peasants tormenting a Jewish child.” As it turned out, Kosinski’s memoir was really a work of fiction.

The American Jewish comedian Lenny Bruce, succumbed to misleading generalizations, too. In one of his sardonic skits, he recklessly defined antisemitism as “two thousand years of Polak kids whacking the shit out of us coming home from school.”

Which leads Goska to write pointedly: “When a Pole exhibits what appears to be positive or neutral attitudes or behaviors toward Jews, that must be understood as a temporary failure of his antisemitic essence to fully express itself.”

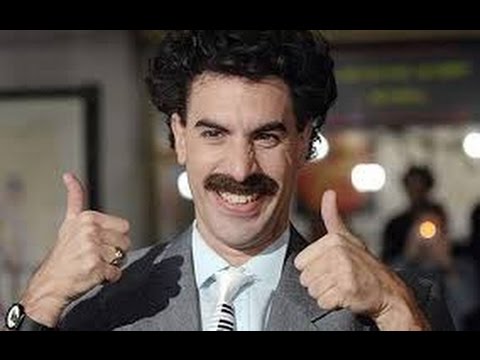

In her opinion, Sasha Baron Cohen, the British comedian, is the chief propagator of the Bieganski slur today. Through his fictional character, Borat — a filthy, stupid, anti-Jewish buffoon — Cohen perpetuates the myth of the uncouth antisemitic Pole, the flip side of the conniving, untrustworthy Jew. “Borat identifies himself as being from Kazakhstan,” she writes. “Nevertheless, it is clear to many, including Kazakhs, that Cohen’s jokes target Poland (and Poles) rather than the Central Asian, largely Muslim Kazakhstan.”

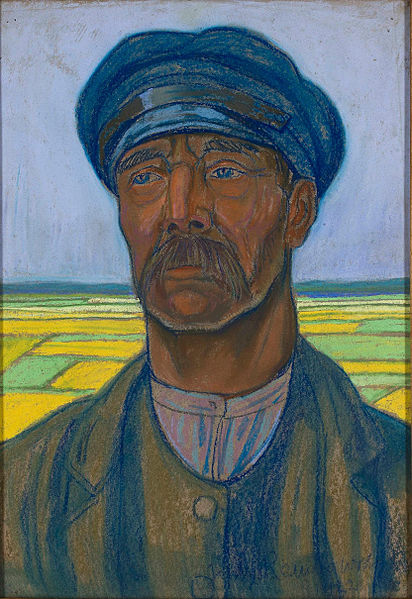

Goska’s assumption that Kazakhs are actually Poles is debatable, but she’s on firmer ground when she delves into the roots of the Bieganski trope. “The taint derives from an ethnic interface between one group, Jews, who had, relatively, better formal education, greater sophistication and mobility, and their view of Poles, who, for the most part, and for most of Polish history, were peasants.”

Peasants, however, were not the only Polish figures held in contempt by some Jews. “In Jewish folklore and literature,” she says, “Polish noblemen are often amoral beasts who ruin themselves, their peasants, Jews and Poland through greed and irrational spending.”

Negative images of peasants are found as well in Polish folklore, as the scholar Ewa Korulska points out. Peasants exhibit exemplary characteristics such as common sense and love of family, but they also display cruelty and ignorance, she notes. The distinguished historian Norman Davies is similarly ambivalent about the Polish peasantry, Goska goes on to say.

In the United States, Poles have been both admired and scorned. In the wake of the failed 19th century insurrection in partitioned Poland, Poles were generally regarded as dashing and romantic. But with the influx of Polish immigrants into the United States from the 1880s onward, the average Polish newcomer was no longer seen as a “freedom-loving hero on horseback,” but as “an animal (and) breeding machine whose fecundity was a threat,” she observes.

In Tennessee Williams’ play, A Streetcar Named Desire, one of the characters, Stanley Kowalski, is perceived pejoratively as a “Polak.” As Goska puts it, “Stanley is spectacularly offensive. He wears a sweat-stained T-shirt and scratches at his nipples; he strips in front of a strange woman; he drinks whiskey from a bottle; he smacks his wife on the rump in front of his friends…”

In her chapter, Bieganski as a Support for Jewish Identity, Goska cites Jewish sources to advance the questionable claim that “a sense of victimization has become central to creating and maintaining modern Jewish identity” in the United States. “The Poland of the Statute of Kalisz, or even the Poland of Jan Karski, is not a player here,” she writes in reference to a positive period in Polish-Jewish relations and one of the upstanding personalities in modern Poland. Instead, she claims, “cursed” Poland is central to building Jewish identity.

Goska goes astray here. The formation Jewish identity is not and has never been dependent on the denigration of Poland, where Jews have lived continuously for 1,000 years. Bieganski is generally a thoughtful account of one facet of the complex relationship between Poles and Jews, but it’s marred by superficial observations such as the one above.