There are now 225 Jewish settlements and outposts in the West Bank, conquered by the Israeli army during the 1967 Six Day War. Since then, Israel and the West Bank have morphed into a single geo-political unit. This inescapable reality has enormous ramifications on the long-simmering Arab-Israeli conflict. Israel’s armed presence in the West Bank means that a two-state solution may never materialize, leaving Israel and the Palestinians in a state of permanent conflict.

How Israel reached this incendiary point is the subject of Shimon Dotan’s illuminating, hard-hitting documentary, The Settlers, which opens in Toronto on March 17 for a one week run at the Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema (506 Bloor West).

Dotan’s film unfolds in chronological order and advances the thesis that the settlements, currently populated by more than 400,000 Jews, were conceived and constructed with the express purpose of blocking Palestinian statehood.

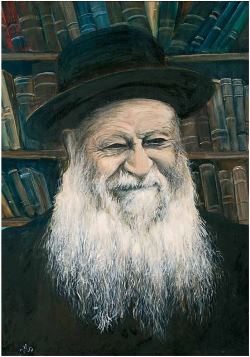

Dotan, an Israeli Canadian, argues that the godfather of the settlement movement, Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook, was a messianic nationalist who never recovered from the trauma caused by the partition of Palestine, the biblical Land of Israel. In an impassioned speech on the eve of the Six Day War, he told fervent followers that Jews had a solemn duty to reclaim their historic homeland. “They divided our land,” he declared indignantly. “Where is our Nablus? Where is our Hebron? Where is our Jericho? Where is our Trans-Jordan?”

As a result of the lightning war, Israel acquired the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, the Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights, thereby tripling the size of its territory. Israel eventually relinquished Gaza and Sinai, but still maintains an iron grip on the Golan and the West Bank.

To religious Jews like Rabbi Yoel Bin Nun, Kook’s disciple, Israel’s acquisition of the West Bank was the apotheosis of divine redemption, an opportunity not to be squandered. Bin Nun’s friend and ideological soul mate, Hanan Porat, petitioned Israeli Prime Minister Levi Eshkol to revive Gush Etzion, a cluster of Jewish settlements near Jerusalem Jordan’s Arab Legion had captured during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. Eshkol, a moderate Labor Zionist, was hesitant, fearing Israel would be in violation of the Geneva Convention if he acceded to Porat’s request. Eshkol’s colleague, Yigal Allon, was resolute, firmly believing that Israeli settlements in the Jordan Valley could serve a strategic purpose.

Yitzhak Rabin, the chief of staff of the Israeli armed forces during the 1967 war, succeeded Golda Meir as prime minister in 1974. Dubious about the utility of settlements, he let it be known he would not tolerate the construction of unauthorized ones. The settlers, however, paid no attention and pushed ahead with plans to build settlements under the auspices of Gush Emunim, a new organization dedicated to reclaiming Judea and Samaria for Israel.

Rabbi Moshe Levinger, one of their leaders, argued that settlers would not be taken seriously by the Israeli government unless they created facts on the ground. And so the settlement of Kiryat Arba, near Hebron, was created. As Dotan observes, the government neither approved nor rejected the project, essentially leaving the initiative in the settlers’ hands.

Menachem Begin’s election as Israel’s prime minister in 1977 heartened the settlers. Begin, a Zionist Revisionist, considered the West Bank an integral part of the Land of Israel. He instructed one of his key ministers, Ariel Sharon, to launch a massive settlement drive. It changed the political landscape of the West Bank, then inhabited by more than one million Palestinians.

In Dotan’s film, the settlers come across mostly as zealots. A man named Yehuda Etzion condescendingly reduces Palestinian Arabs to guests in their native land. Mati Bloomberg, a young woman whose home sits on a Palestinian farmer’s land, menacingly implies he may lose it in the future. Moti Karpel, a settler who seems well versed in history, admits that Jews invaded Arab lands but claims that Arab resistance to Zionism prompted Israeli territorial expansion. Another settler says that Arabs don’t belong in “our country.” Still another one contends that Israel’s borders should stretch from the Nile to the Euphrates.

Given their hardline views, the settlers staunchly opposed the 1993 Oslo accords. Two of them, Baruch Goldstein and Yigal Amir, committed acts of terrorism in defence of their beliefs. Goldstein killed 29 Palestinians in a mosque in Hebron, setting off a Palestinian campaign of suicide bombings. Amir assassinated Rabin during his second term as prime minister, crippling the Oslo peace process and enabling the rise of Benjamin Netanyahu, an opponent of territorial compromise.

As it winds down to its denouement, The Settlers covers the outbreak of the second Palestinian uprising in 2000, the massive expansion of outposts between 1995 and 2005, Israel’s unilateral withdrawal from Gaza in 2005 and the role played by American evangelical Christians in support of the settlers.

It’s a must-see film for those interested in understanding the dynamics of contemporary Israeli politics and the bitter divisions of the Arab-Israeli dispute.