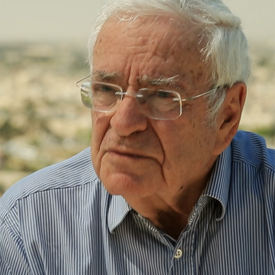

Japan’s attitude to and policies toward Jews from 1933 to 1945 — the years that coincided with the rise and fall of Nazi Germany — is the subject of Meron Medzini’s fine and fascinating work of scholarship, Under the Shadow of the Rising Sun: Japan and the Jews During the Holocaust Period, published by Academic Studies Press.

The historiography of the Holocaust is rife with books about the mass murder of European Jews, yet Japan — a member of the Axis alliance and a close ally of Nazi Germany — is rarely mentioned in this grim catalog of terror and mass murder. The reason is clear. While many of the 40,000 Jews living in Japan and its overseas possessions were subjected to restrictions and theft of property due to their status as foreign nationals, they were not humiliated or persecuted because they were Jews. Nor were they singled out for extermination. Indeed, one Japanese diplomat single-handedly saved thousands of Jews.

Medzini, a Hebrew University historian, is one of the few scholars who has exhaustively delved into this intriguing topic. Nevertheless, it remains still largely untapped. Even Yad Vashem — the Holocaust memorial and education centre in Jerusalem — has yet to publish a major study on it, as he notes in the introduction.

In the meantime, Medzini’s wide-ranging book fills the gap quite admirably. He deals with the influx of Jews into Japan from the mid-19th century, the image of Jews in Japanese society, the export of antisemitism to Japan, the treatment meted out to Jews in Japanese-occupied Manchuria, China and Southeast Asia and the policies Japan formulated with respect to Jewish refugees.

Portuguese conversos — Jewish converts to Christianity — were the first Jews to visit Japan. Jewish traders and entrepreneurs established themselves in Japan in the late 1850s, following the arrival of an American flotilla commanded by Mathew C. Perry. The majority of the newcomers were initially from Southeast Asia, China and Western Europe. Later, Jews arrived from the Middle East, Eastern Europe and the United States. They largely settled in the cities of Nagasaki, Yokohama and Kobe.

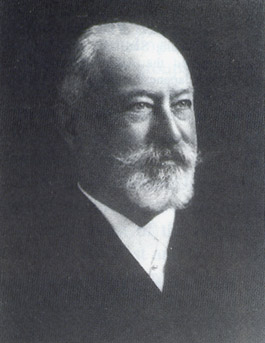

The majority of Jewish migrants were businessmen, but Albert Mosse, a German Jew, played an important role in the development of the 1889 Meiji constitution. Still other Jews, though not residents of Japan, were of immense assistance to the country. The American banker and financier, Jacob Schiff, was instrumental in securing loans for Japan during its war with Russia.

Medzini claims that The Merchant of Venice, translated into Japanese in the 1880s, had an impact on Japanese perceptions of Jews. “Many Japanese readers thought that the typical Jew was Shylock: clever, sly, untrustworthy, and given to devious intrigues and manipulations,” he writes, adding that this stereotype would reappear with greater strength from the 1920s onward. Japan’s ruling elites had a keen interest, verging on admiration, for Jews, whom they believed possessed special talents in finance and international politics and wielded vast influence over governments.

Antisemitism seeped into Japan after Japanese forces entered Siberia in 1918. Japanese officers, having been exposed to White Russians who poured scorn on the 1917 Bolshevik revolution and displayed hatred of Jews, brought back these ideas to Japan. By no coincidence, the army officer who translated the Protocols of the Elders of Zion into Japanese had been posted in Siberia. An infantry officer, General Shioden Nobutaka, would become the most well-known and outspoken antisemite in Japan during the 20th century. He had been influenced by French antisemites while serving as Japan’s military attache in Paris during World War I.

Nevertheless, the few thousand Jews living in Japan before World War II were never seen as fifth columnists determined to undermine Japanese culture, says Medzini. “They were, at best, part of the foreign community, and therefore they did not arouse the passionate, often hysterical response (Jews) encountered in Nazi Germany. Since they were never seen as an integral part of Japan, and subsequently were not viewed as enemies of that country, Japan’s society saw no need to destroy them.”

Nazi ideas infiltrated into Japan toward the end of the 1930s as Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf and Alfred Rosenberg’s The Myth of the Twentieth Century were retranslated and distributed. These turgid tracts may have reinforced the Japanese notion that Jews were disseminators of liberal, secular, universal, democratic and Marxist ideas.

The Japanese government supported Zionist aspirations for a Jewish national homeland in Palestine and endorsed the Balfour Declaration when it was issued by Britain in November 1917. In explaining why Japan backed the Zionist movement, Medzini says Japanese decision-makers had an inflated view of Jewish power and placed the Middle East low on the totem pole of Japan’s priorities.

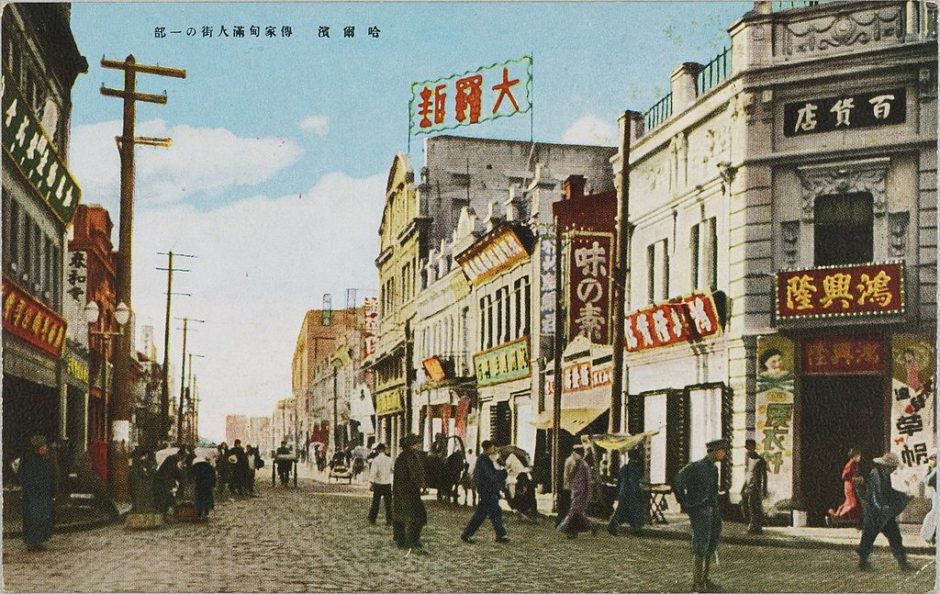

Outside of Japan, Jews found themselves under direct Japanese rule after Japan’s occupation of Manchuria in 1931. Many of these Jews lacked any nationality and sought the protection of the Japanese army. Japan acceded to their request, hoping its benevolence would prompt wealthy Jews to invest funds in the development of Manchuria’s vital coal and steel industries.

Japan’s fixation with Jewish capital gave rise to the Fugu Plan, a scheme hatched in 1934 by the president of the Southern Manchurian Railway, Matsuoka Yosuke, to lure 50,000 German Jews to Manchuria. Key officials in the Japanese government supported it, but it remained still-born, never having been accompanied by a detailed operational plan.

Nonetheless, Japan cultivated a relationship with Jews. A senior Japanese army officer who addressed a meeting of the First Congress of the Jews in East Asia in Harbin in 1937 told delegates that Japan held no prejudices against Jews, did not subscribe to racist ideology, welcomed friendly ties with Jews and was ready to cooperate with them in economic and commercial spheres. After Japan joined the Axis Pact in 1940, the Japanese foreign minister, speaking on behalf of Japan’s emperor, told Lev Zykman, a leader of Harbin’s Jewish community, that Germany’s antisemitic policies did not obligate Japan to adopt the same position.

The Jewish refugee question turned into an important issue for Japan because it was bound up with German-Japanese relations. “The problem was how to avoid doing anything positive for Jews that would harm Japan’s ties with Nazi Germany while also avoiding alienating American Jews, whose economic power was seen by Japan as dominant,” writes Medzini.

Given such conflicting considerations, he goes on to say, Japan struck something of a compromise toward refugees, deciding that no visas would be issued to stateless Jewish refugees and that Jews holding valid German and Austrian passports should be persuaded to seek shelter in countries other than Japan. Jews already holding entry visas to a third country would be permitted to obtain transit visas to Japan.

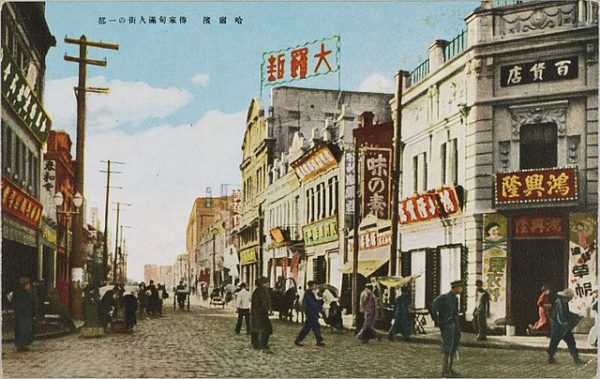

Medzini’s chapter on Shanghai deals, of course, with refugees. From 1938 to 1941, 15, 450 Jewish refugees, the bulk from Germany and Austria, streamed into the Chinese city of Shanghai, which came under direct Japanese rule in the summer of 1937. By then, there was already an established Jewish community there. The first wave of Jewish settlers had arrived from Iraq, Persia and India in the middle of the 19th century, followed by Russian Jews in the wake of the Bolshevik revolution.

Jews arriving in Shanghai from the late 193os onwards did not require entry and residence permits. Japan treated them and other foreigners fairly while maintaining close surveillance over their activities. The situation changed after the arrival of German colonel Joseph Meisinger in July 1942. The Gestapo’s senior representative in Japan, he had committed war crimes against Jews in Poland.

In conversations with Japanese army officers, Meisinger called for a series of stringent measures to be enacted against Jews in Shanghai. Japan rejected most of his draconian suggestions, but on February 18, 1943, Japanese authorities established a “designated area” for 14,000 stateless Jewish refugees in the working-class district of Hongkew. Russian Jews were excluded from this ordinance. Life was hard for the residents of the Hongkew ghetto, but they were not physically molested, and American Jewish organizations were permitted to send funds for their upkeep.

Jews residing in other Japanese-controlled Chinese cities, like Mukden and Tianjin, were not harmed either. But in Hong Kong, Manila, Singapore, Batavia and Rangoon, the local Japanese ruler confiscated the homes and real estate holdings of Jews, froze their bank accounts and seized their gold and jewels. In Thailand, an ally of Japan until almost the end of the war, Jews with U.S. and British passports were interned. German, Austrian, Iraqi and Syrian Jews were left alone. In keeping with its stated policy of maintaining racial harmony in the occupied areas, Japan gave short shrift to Germany’s genocidal approach to Jews.

Whenever possible, however, Japan tried to mollify Germany. The case of Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese vice-consul in Kaunas, Lithuania, is indicative of Japan’s balancing act. The Japanese government forbade him to issue transit visas to Japan to a group of Polish Jews, but he ignored his superiors’ order and issued 6,000 visas for individuals and entire families. Among the Jews he rescued from 1940 onwards were 300 rabbis and yeshiva students. After being transferred to Berlin, he issued 69 transit visas to German Jews.

In Japan itself, American and British Jews were interned, but Jews holding other foreign passports seem to have faced no problems. Neither the emperor nor government ministers ever issued statements about Jews, but in 1944, the home minister made it clear that Japan’s policy was to eradicate discrimination based on race.

Still, 170 antisemitic books were published in Japan from 1936 until 1945. Some major dailies, notably Asahi Shimbun, carried antisemitic articles, but refrained from publishing stories about Nazi atrocities in Europe. The German embassy in Tokyo disseminated anti-Jewish material to the Japanese media, but the Nazi regime never considered the Jewish Question a high priority issue in its deliberations with the Japanese government. In any event, most Japanese people were oblivious to Jews and, therefore, antisemitism.

Documents examined by Medzini indicate that Japanese officials had little or no detailed information about the Holocaust. “There were virtually no Japanese reports of the mass killings of Jews,” he says. Japanese diplomatic and consular documents relating to Jews focused instead on visas and other matters pertaining to Jewish migration.

In short, as Medzini suggests, Japan was neither obsessed by Jews nor infected by antisemitism.