Victor Orban hates Western liberal values and makes no secret of it. Of late, this has led to a major row with American financier George Soros and Michael Ignatieff, Canada’s former Liberal Party leader.

The fate of the Central European University (CEU), located in Budapest, hangs in the balance and its future will depend on which side prevails.

Orban, Hungary’s prime minister since 2010, is trying to shut down the school. It’s all part of a larger battle he’s waging against Western institutions. He has also ordered a crackdown on foreign-funded non-governmental organisations, or NGOs.

A new law passed in June requires NGOs that receive more than $26,000-a-year from overseas to register with the authorities and to declare their “foreign status” online and in all press kits and publications.

Critics say the law is intended mainly to stifle independent points of view and to stigmatize as unpatriotic those groups that receive support from Western philanthropists and foundations.

Orban has especially focused on those NGOs funded by the Open Society Foundations, the international grant-making network founded by the Hungarian-born Soros. Orban considers them a “mafia-style operation” with paid political activists who threaten national sovereignty.

They “serve global capitalists and back political correctness over national governments,” remarked Szilard Németh, a vice-president of the ruling party Fidesz.

“In Hungary the national government is under continuous pressure and attacks,” Orban stated in April, so what is at stake “is whether we will have a parliament and government serving the interests of Hungarian people” or “foreign interests.”

He called Soros an “American financial speculator attacking Hungary” who has “destroyed the lives of millions of Europeans.”

Soros, in turn, has denied he was trying to interfere in Hungarian politics. “He sought to frame his policies as a personal conflict between the two of us,” Soros said about Orban at the annual economic forum of the European Commission, the EU’s executive arm, earlier in June.

Soros has explained that his fight against intolerance is rooted in his own experience of living through the Nazi occupation of Hungary. Born in Budapest to a well-to-do non-observant Jewish family, Soros was 13 years old in March 1944 when Nazi Germany occupied the country.

His family survived by hiding its Jewish identity, with Soros posing as the Christian godson of a Hungarian official. After the war, he moved first to England and later to the United States. Eventually, he became fabulously wealthy as an investment banker and hedge fund manager.

The Bloomberg Billionaires Index, a ranking of the world’s richest people, estimates his fortune today at some $25 billion.

He has given away $12 billion to date, according to his Open Society Foundations. Of that, $400 million has gone to Hungary. Yet for Orban, Soros is literally the enemy of the nation.

The 86-year-old is increasingly accused by nationalists of using his money to force his liberal values, including support for refugees, on their societies.

It feeds into age-old antisemitic stereotypes of Jews as “rootless cosmopolitans” seeking to destroy Christian societies. (No Zionist, Soros takes a jaundiced view of Israel’s policies.)

Szuszanna Szelenyi, an opposition lawmaker who in the 1990s was a member of Orban’s Fidesz party, told the New York Times that in the last two years, the government has advanced a “conspiracy theory” arguing that Soros, who “embodies global capital, has been exerting his influence, through his money, in the entire world.”

Hungarian Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto has insisted that Budapest’s disputes with Soros have “absolutely nothing to do” with his Jewish origins.

But Mark Weitzman, director of government affairs for the Simon Wiesenthal Center, a Jewish human rights group, sees the rhetoric as “reminiscent of previous antisemitic patterns.”

“This is not to say that Soros should be above criticism. But there are certainly other elements involved that go beyond legitimate and specific criticism and focus on his Jewish roots,” Weitzman said. There’s a need by some “to create a global manipulative Jewish monster which can be blamed for all the evils and problems.”

Orban’s government has for years tried to gain control of the country’s institutions of higher education. It now appoints powerful chancellors and tries to shape what is taught.

But the CEU remained beyond his reach. Founded in 1991, soon after Hungary emerged from decades of Communist rule, and financially supported by Soros, it operates mainly in English and concentrates on post-graduate education.

Its focus has been global, with a special emphasis on democracy promotion and human rights around the world.

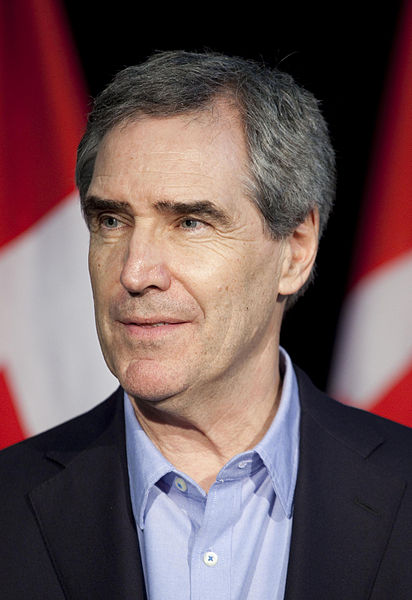

In 2016, Ignatieff became the university’s fifth president. He has a longstanding connection to Hungary, his wife Zsuzsanna Zsohar being Hungarian-born.

“Dr. Ignatieff is a scholar and policy practitioner and as such is ideally suited to lead CEU in these challenging times,” remarked Soros at the time.

But the Hungarian government has accused the university of trying to undermine Hungary’s political culture. Fidesz has referred to the CEU as “Soros university,” and sees it as a bastion of liberalism and privilege.

The university has an endowment of over 500 million euros (over $740 million), in a country where incomes are well below the European Union average.

In April the Hungarian parliament voted in favor of legislation placing tough restrictions on foreign-registered universities. It requires them to have a campus both in the capital and their home countries. The CEU has a campus only in Budapest.

Those working at the CEU will in future require work permits, which the institution says will limit its ability to hire staff.

When demonstrators protested against the legislation, government-friendly media suggested that all the protesters had been paid and flown in by Soros. Soon after, the demonstrators started to hold up paper airplanes with “Soros Airlines” written on them and chanted “We came by plane.”

Ignatieff and the university have secured the support of the European Union, which has launched legal action against Hungary over its new law, claiming that the bill violated fundamental EU values such as academic freedom.

In May, a majority in the European Parliament voted for a resolution asking Hungary to repeal the law. As well, Isabelle Poupart, Canada’s ambassador in Budapest, said in a statement that Canada was “seriously concerned” about the new law.

But Hungary has not backed down. “The regulation of higher education is a member-state competency, not the EU’s,” responded Zoltan Kovacs, a Hungarian government spokesman.

“All this seems like a coordinated attack not just on academic freedom but on freedom of association, and, finally, on democratic freedom,” contends Liviu Matei, provost of the CEU.

For the first time in Europe since World War II, a university will have been closed for political reasons.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.